Alan: For decades, American conservatives have been outraged by the word "meanspirited" when applied to Republican partisans. Now that Republican "leadership" has reaped in Trump what it has sown in anger, contempt and (largely racial) animus has begun using the work "hatred" to epitomize Trump, can those of us who didn't go crazy finally describe Republicans for what they are - consistently "mean-spirited?""The Hard, Central Truth Of Contemporary Conservatism"http://paxonbothhouses.

They have not been the party of Lincoln for decades: Donald Trump exposes the truth about GOP racism that David Brooks keeps denying

David Brooks keeps pretending his is the party of Lincoln. Sure, in 1864. Maybe he should catch up with reality

Trump’s situation is anything but unique—it’s just a bit more raw than it is with other Republicans. Ever since the 1960s, as Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy was being born, there’s been an ongoing dilemma (if not huge contradiction) for the erstwhile “Party of Lincoln” to manage: how to pander just enough to get the racist votes they need, without making it too difficult to deny that’s precisely what they’re doing.

Now, however, things have really come to a head. Trump’s full-throated defense of Social Security and Medicare—plus his promise not to let people “die in the streets” for lack of health care coverage—put him directly at odds with “small government conservatism,” driving movement conservative leadership nuts, even as Southern whites formed the strongest core of his support. As Corey Robin explained hererecently, that doesn’t for a moment mean that Trump isn’t a conservative, simply because he comes from outside their ranks and promotes some unorthodox views:

Outsiders like Burke or Thatcher—even Donald Trump, who’s never been a Republican, much less an officeholder—have always been necessary to the right. They know how the insiders look to ordinary people—and how they need to look.

Outsiders like Burke or Thatcher—even Donald Trump, who’s never been a Republican, much less an officeholder—have always been necessary to the right. They know how the insiders look to ordinary people—and how they need to look.

They need to look like they’re going to take charge of things—not continue to let them fall apart. That’s Trump’s “Make America great again” rationale in a nutshell: conservative elites have failed to deliver, it’s time for an outsider to take over. An outsider just like Richard Nixon always felt himself to be, who speaks pointedly about the return of Nixon’s “silent majority”; who harps on Nixon’s authoritarian/ethnocentric themes of “law and order,” even to the edge of inciting violence; has a “secret plan” to win America’s most troubling, intractable war; and yes, runs very effectively on his new version of Nixon’s “Southern Strategy”—that’s Donald Trump to a “T.”

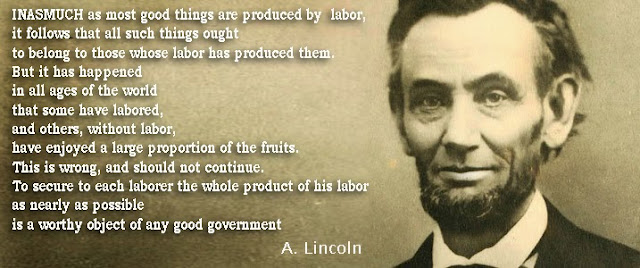

Alan: If your a fool for punishment, try to get Republican friends to circulate this Lincoln poster.

"Are Republicans Insane?" Best Pax Posts

http://paxonbothhouses.

http://paxonbothhouses.

Trump’s Southern Strategy

With that March 8 win, Trump completed his sweep of Deep South states—South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, racking up 168 delegates to Ted Cruz’s 62, almost 66 percent of the total. By that time, he had also won four other Southern or border states: Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee and Arkansas—good for another 83 delegates to Cruz’s 53. His victories weren’t limited to the South, of course, but outside of Ted Cruz’s lock on his own home state, Trump’s dominance in the South was unparalleled elsewhere, as well as representing a substantial base of his strength. Outside this group of Southern states, Ted Cruz had actually gained more delegates than Trump. When Trump added wins in Florida and North Carolina a week later, his sweep of South, outside of Texas, was complete. Add the border state of Missouri, and he had a 60 percent margin minus the Deep South. If he’d been doing as well everywhere, the race would have been effectively over. There’d by no talk of a brokered convention.

The role racism played in this could be spotted early on. After the South Carolina primary, in a post at his Family Inequality blog, “Looks like racist Southern Whites like Trump,”sociologist Philip Cohen wrote, “In counties with less than 40% of the population born out of South Carolina — 33 of the 46 countries — there is a strong positive relationship between Trump vote share and population proportion Black.” Higher black populations make race more salient for whites, and this produces more racist attitudes, as this chart illustrates, using state-level Google searches for n-word jokes.

A week before the Mississippi vote, Marco Rubio had defiantly declared that “The Party of Lincoln and Reagan, and the presidency of the United States will never be held by a con artist,” meaning Trump. But Trump’s Southern-centered success was a stark reminder that there actually is no “party of Lincoln and Reagan.” The name of the party may be the same, of course, and there’s an institutional continuity over time, but any notion of the GOP as embodying high ideals shared by those two men, which Trump betrays, is simply ludicrous. There’s a party of Lincoln and a party of Reagan. Trump belongs to the latter, not the former.

The Southern Strategy and the Party of Anti-Lincoln

The party of Lincoln was driven out by angry Goldwater delegates at the 1964 convention. That year, the GOP won just five states [map] in addition to Goldwater’s home state of Arizona—the five Deep South states where Trump out-polled Cruz in delegates by almost 3-1. A scant eight years earlier, Democrats had won four out of five of those states—and just three other states nationwide: two adjacent Southern states and the border state of Missouri [map]. The electoral college maps of 1956 and 1964 are almost mirror images of one another. It’s as if the two parties had switched bodies—or souls. And so it has turned out to be.

Goldwater himself was not a racist. He was a small-government conservative. But the wave of white Southern voters who supported him were not, and they did not change their spots in the decades to come, as they gradually shed the generations-long traditional trappings of calling themselves Democrats, and became the GOP’s red state base. I’ve gone over this in my earlier stories linked to above. Three key points in particular are worth keeping in mind:

- The paper “Why did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate” found that racism can explain all of the decline of Southern white support for Democrats between 1958 and 1980, and 77 percent of the decline through 2000.

- The paper “Old Times There are Not Forgotten: Race and Partisan Realignment in the Contemporary South” found that “whites residing in the old Confederacy continue to display more racial antagonism and ideological conservatism than non-Southern whites. Racial conservatism has become linked more closely to presidential voting and party identification over time in the white South.” This is the exact opposite of what Republican apologists have tried to pretend.

- The 1967 book “The Political Beliefs of Americans: a Study of Public Opinion“found a sharp difference between ideological orientations expressed in broad terms, with half of all respondents qualified as ideological conservatives, versus specific support for government spending programs, and two-thirds qualified as operational liberals. As a result, I noted, “almost a quarter of the respondents, 23 percent, were both ideological conservatives and operational liberals. What’s more, this percentage doubled in the handful of Deep South states that Goldwater carried that year.” [emphasis added] This vividly underscores how irrelevant the notion of “small government conservative” is for explaining white Southern behavior even where it does exist rhetorically.

This is the underlying hard data reality undergirding the reality of the Southern Strategy. It complements the narrative tale told by Jeet Heer at the New Republic in late February, “How the Southern Strategy Made Donald Trump Possible,” in which he highlights the role played by movement conservatives, particularly the National Review. “It’s essential to remember that the Southern Strategy did not originate with cynical GOP pols and right-wing extremists,” Heer writes, “but was—ironically enough—first hammered out in the pages of National Review, the very publication that nowexcoriates Trump as ‘a philosophically unmoored political opportunist who would trash the broad conservative ideological consensus within the GOP.’” Naturally, Heer cites the infamous 1957 editorial endorsing Southern racism, though only as one notable signpost along the way. But to really grasp how politically effective the Southern Strategy has been, you have to account for racial attitudes in national politics. Here there are two key points I’ve made:

- Racial attitudes play an overwhelming role in producing “small government conservative” views. A key indication of racial attitudes is whether people think blacks’ relative lack of economic success is due to external factors, such as discrimination, or to internal ones, such as lack of will. Using data from the General Social Survey, I reported that those blaming internal factors were almost four times more inclined to cut social spending, using a seven-item index, than those who blamed external factors: 17.3 vs. 4.5 percent. Hence racial attitudes are clearly a driving force in what’s retroactively justified as “small government conservatism.”

- Racial attitudes play a key role in unifying the GOP, and splitting Democrats by region. In a 2014 story, I reported that views in the Democratic Party had changed dramatically since the 1970s, while views in the GOP had not. Among Democrats, the ratio of those citing only external vs. only internal reasons has been more than cut in half –from 2.1/1 to 1.0/1. In the GOP, the ratio has declined just 7 percent, from 3.8/1 to 3.5/1. What’s more, Democrats within the white South (2.3/1) are similar to Republicans outside it (2.7/1).

Toward the end of that story, I concluded:

What all the above boils down to is that blaming blacks for being poor remains broadly popular in America today, and that taking note of continued discrimination is not. A modest majority of Democrats outside the white South disagree, and this creates a political fault line that Republicans have repeatedly exploited across the decades, with no end in sight. When conservatives get too crude — as was the case with Cliven Bundy, for example — this threatens to upset the apple cart, and appearances must quickly get restored. But it’s the crudity, not the underlying attitude of blaming blacks, that has fallen out of favor.

Trump Shakes Things Up—Or Was It Obama?

Obviously, Trump’s rise shows that something has changed, even as the GOP establishment still believes this same calculus holds. Running against Obama in the 2012 primary season, their racism repeatedly erupted into open view, and had to be repeatedly explained away. Trump speaks for those who no longer feel apologetic. As Jamelle Bouie explained recently, Obama’s presidency triggered the reaction, in ways that polite society simply doesn’t wish to acknowledge:

No comments:

Post a Comment