Pope Francis: There Are Two Ways Of Having Faith: We Can Fear To Lose The Saved," Or...

Misunderstanding Pope Francis:

the secular outlook and the scandal of the Cross

Back in March , Pope Francis told visiting bishops from Bosnia-Herzegovinathat the Church “cannot stay closed within its traditions, noble though they may be.” He went on: “It must come out of its 'enclosure', firm in faith, supported by prayer and encouraged by pastors, to live and announce the new life of which it is a depository, that of Christ, Savior of all men.”

This has been the most important and consistent theme of the current pontificate: the need for the Church to look outward, toward a world in need of salvation—the call to be apostolic rather than “self-referential,” to care more about serving those in need than tending to in-house problems, to favor the work of evangelization over administration.

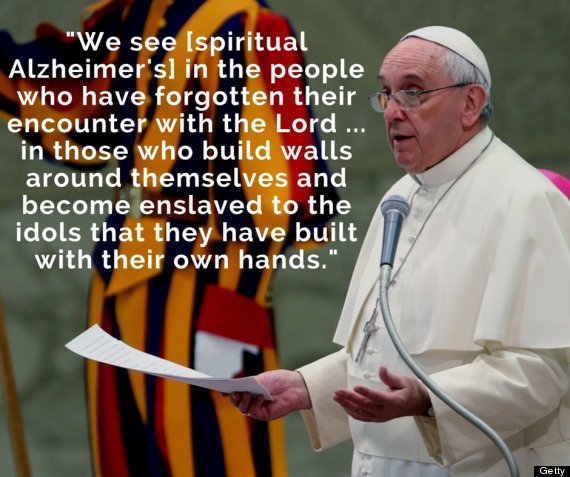

”There are two ways of thinking and of having faith,” the Holy Father said on February 15, as he concelebrated Mass with the newest members of the College of Cardinals. “We can fear to lose the saved, and we can want to save the lost.”

By now we all know which route Pope Francis prefers. He wants to save the lost. Dig a little deeper into his public statements, and you realize that he does not think this is an either/or proposition. The self-referential Church, preoccupied with fear of losing the faithful, becomes calcified, and loses them anyway. In an energetic, apostolic Church, the faithful are caught up in the excitement of saving the lost.

Jesus never told his disciples to circle the wagons and be careful. Quite the contrary; He told them not to hide their lights under bushel baskets. He challenged them to be the leaven the world needs, to go out and baptize all nations. Pope Francis echoes that mandate.

But how do we carry out the Lord’s command?

Pope Francis has won worldwide attention by reaching out beyond what many people, inside and outside the Church, perceive as the boundaries of Catholicism. His concern for the poor, his insistence that Christians must help those in need, have earned him the respect of the secular world. Even beyond that, his anxious willingness to establish a relationship with those who are far from the Church has won plaudits. That fateful phrase, “Who am I to judge?” captured the imagination of a public that is ordinarily not interested in the thoughts of the Roman Pontiff.

But while they understandably emphasize the Pope’s determination to help those who are in need and those who have strayed—to rescue the lost sheep—pundits run the risk of missing another important dimension of the Pontiff’s work. Yes, he wants to bring help to the poor. But he has repeatedly stressed, echoing a message of Pope Benedict XVI, that the Catholic Church is not just another charitable agency. Yes, he wants to open conversations with people who have been alienated from the Church. But he does not intend to rewrite the Catechism of the Catholic Church to make it politically correct.

Pope Francis urges the faithful to “reach out” to their neighbors, and no one with a heart for evangelization should fail to recognize the necessity of that effort. But having reached out, what comes next? Once the conversation has begun, what do we say? Once we have fulfilled the immediate needs of the hungry and the homeless, and settled down for a friendly conversation, what should we tell them?

To some secular commentators those questions would seem irrelevant. Proponents of what Notre Dame’s Christian Smith has characterized as “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism” act on the assumption that there is no particular message the world needs to hear from Christians—aside, perhaps, from the injunction that we should all “be nice.” Bishop James Conley recently summed up the approach:

The dogma of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism is this: God exists, and desires that people are good, nice, and fair to one another. God can be called upon to assure happiness and to resolve crises. Being good, nice, and fair assures eternal salvation in heaven.

If you assume that Pope Francis subscribes to Moralistic Therapeutic Deism (MTD), there is no reason to look beyond his concern for the poor and his unwillingness to judge. He is following the most important mandate of the MTD creed; he is being nice. Since the apostles of MTD have a marked tendency to assume that others believe as they do, the matter goes no further.

But if you listen at all carefully to the Pope’s public statements, you hear notes that cannot be harmonized with the MTD approach. Have you noticed, for instance, how frequently the Holy Father speaks about the Devil? Just a few weeks ago, speaking about how Mexico is torn by murderous drug-trafficking gangs, the Pope suggested that “the devil has not forgiven Mexico” for the appearance of Our Lady of Guadalupe. He said: “That's my interpretation. In other words, Mexico is privileged by martyrdom, because it has recognized and defended its Mother.” The secular world, trained to think of evil only in abstract terms—only in terms of deprivation—shies away from such thoughts.

Or consider what the Pope says about today’s Christian martyrs. Yes, he mourns their suffering, and decries the silence of world leaders in the face of persecution. Those statements are compatible with MTD. But he also speaks of the “beautiful witness of Christian living” provided by modern-day martyrs, and says that all Christians should imitate their zeal. That sort of statement goes beyond the comprehension of comfortable secularists. It’s one thing to be kind to others; it’s quite another thing voluntarily to endure suffering and death.

The scandal of the Cross. The secular world can accept Christianity, tolerate Christianity, even applaud Christianity, as long as Christianity provides material benefits. But when the faithful turn toward Calvary, the world prefers to look away. Pope Francis urges us to “reach out” so that the world will listen to the good news of the Gospel; unsympathetic analysts notice only that he has “reached out,” without knowing why.

On Palm Sunday, in St. Mark’s account of the Passion, we read what the people who witnessed the Crucifixion said of the Lord:

Let the Christ, the King of Israel, come down now from the cross that we may see and believe.

If Jesus would only come down from the Cross, they would believe, they said.What would they believe? That Jesus had great power to do good? That would be true, of course; but it would only be a part of the truth. They were not prepared to believe that Jesus could conquer sin and death. So, oddly, they said that they would believe in Him—they would embrace him as their savior—as long as He did not carry out his work of salvation.

No comments:

Post a Comment