The Art of Motherfuckitude: Cheryl Strayed’s Advice to an Aspiring Writer on Faith and Humility

by Maria Popova

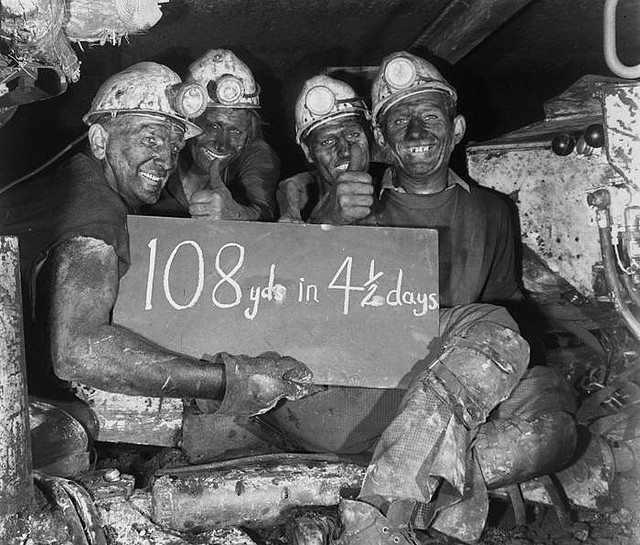

“Writing is hard for every last one of us… Coal mining is harder. Do you think miners stand around all day talking about how hard it is to mine for coal? They do not. They simply dig.”

“Nothing any good isn’t hard,” F. Scott Fitzgerald asserted in his letter of advice on writing to his fifteen-year-old daughter upon her enrollment in high school. That uncomfortable yet strangely emboldening counsel is what Cheryl Strayed offers — with greater poeticism and much better grammar — to a despairing young writer in Tiny Beautiful Things: Advice on Love and Life from Dear Sugar (public library), the ample soul-satisfactions of which have been previously extolled here.

“Nothing any good isn’t hard,” F. Scott Fitzgerald asserted in his letter of advice on writing to his fifteen-year-old daughter upon her enrollment in high school. That uncomfortable yet strangely emboldening counsel is what Cheryl Strayed offers — with greater poeticism and much better grammar — to a despairing young writer in Tiny Beautiful Things: Advice on Love and Life from Dear Sugar (public library), the ample soul-satisfactions of which have been previously extolled here.

Long before Wild — her magnificent memoir of learning, oh, just about every dimension of the art of living while hiking more than a thousand miles on the Pacific Crest Trail — was turned into a major motion picture, Strayed wielded her art as an advice columnist for The Rumpus, simply known as Sugar. Among the thousands of Dear Sugar letters she received was one from a self-described “pathetic and confused young woman of twenty-six” named Elissa Bassist, a “writer who can’t write,” a “high-functioning head case, one who jokes enough that most people don’t know the truth.” “The truth,” she tells Sugar, “[is that] I am sick with panic that I cannot — will not — override my limitations, insecurities, jealousies, and ineptitude, to write well, with intelligence and heart and lengthiness.”

Like all the letters Strayed answered as Sugar, this one is profoundly personal yet speaks to the artist’s universal dance with the fear — the same paralyzing self-doubt which Virginia Woolf so elegantly captured; which led Steinbeck torepeatedly berate, then galvanize himself in his diary; which sent Van Gogh intoa spiral of floundering before he found his way as an artist.

What makes Strayed’s advice so vitalizing is that it is never dispensed as a holier-than-thou dictum; rather, it weaves tapestry of no-bullshit solace from the beautifully tattered threads of her own experience, messy and alive. This is exactly what she hands to Bassist, under the title “Write Like a Motherfucker.”

Invoking the time right before she wrote her first book, when she too was a twenty-something writer plagued by the same fear that she was “lazy and lame,” Strayed recounts how she “finally reached a point where the prospect of not writing a book was more awful than the one of writing a book that sucked”; in other words, she got off the nail. With an eye to Flannery O’Connor’s famous proclamation that “The first product of self-knowledge is humility,” which Strayed had inscribed across the chalkboard in her living room at the time, she writes:

When I was done writing it, I understood that things happened just as they were meant to. That I couldn’t have written my book before I did. I simply wasn’t capable of doing so, either as a writer or a person. To get to the point I had to get to to write my first book, I had to do everything I did in my twenties. I had to write a lot of sentences that never turned into anything and stories that never miraculously formed a novel. I had to read voraciously and compose exhaustive entries in my journals. I had to waste time and grieve my mother and come to terms with my childhood and have stupid and sweet and scandalous sexual relationships and grow up. In short, I had to gain the self-knowledge that Flannery O’Connor mentions in that quote… And once I got there I had to make a hard stop at self-knowledge’s first product: humility.Do you know what that is, sweat pea? To be humble? The word comes from the Latin words humilis and humus. To bedown low. To be of the earth. To be on the ground. That’s where I went when I wrote the last word of my first book. Straight onto the cool tile floor to weep. I sobbed and I wailed and I laughed through my tears. I didn’t get up for half an hour. I was too happy and grateful to stand. I had turned thirty-five a few weeks before. I was two months pregnant with my first child. I didn’t know if people would think my book was good or bad or horrible or beautiful and I didn’t care. I only knew I no longer had two hearts beating in my chest. I’d pulled one out with my own bare hands. I’d suffered. I’d given it everything I had.

Illustration by Kris Di Giacomo from 'Enormous Smallness' by Mathhew Burgess a picture-book biography of E.E. Cummings. Click image for more.

Echoing Voltaire’s memorable admonition from his letter of advice on how to write well — “beware, lest in attempting the grand, you overshoot the mark and fall into the grandiose” — and Bukowski’s lament that “bad writers tend to have the self-confidence, while the good ones tend to have self-doubt,” Strayed adds:

I’d stopped being grandiose. I’d lowered myself to the notion that the absolute only thing that mattered was getting that extra beating heart out of my chest. Which meant I had to write my book. My very possibly mediocre book. My very possibly never-going-to-be-published book. My absolutely nowhere-in-league-with-the-writers-I’d-admired-so-much-that-I-practically-memorized-their-sentences book. It was only then, when I humbly surrendered, that I was able to do the work I needed to do.

Strayed directs her tough-love incisiveness at Bassist’s paradoxical blend of self-pitying defeatism and grandiose entitlement — something not uncommon in young artists, who forget that “anything worthwhile takes a long time,” and a kernel of truth in the otherwise overly flat and ungenerously applied cultural archetype of the millennial:

Buried beneath all the anxiety and sorrow and fear and self-loathing, there’s arrogance at its core. It presumes you shouldbe successful at twenty-six, when really it takes most writers so much longer to get there… You loathe yourself, and yet you’re consumed by the grandiose ideas you have about your own importance. You’re up too high and down too low. Neither is the place where we get any work done. We get the work done on the ground level. And the kindest thing I can do for you is to tell you to get your ass on the floor. I know it’s hard to write, darling. But it’s harder not to. The only way you’ll find out if you “have it in you” is to get to work and see if you do. The only way to override your “limitations, insecurities, jealousies, and ineptitude” is to produce.

Pointing to Bassist’s litany of women writers who ended their own lives — perhaps Plath, Sexton, Woolf — Strayed calls the young writer out on perpetuating the dangerous mythology of creativity and mental illness. Reminding her — reminding all of us — that the stories we tell ourselves shape our horizons of possibility, Strayed reality-checks this perilous narrowing of attention:

In spite of various mythologies regarding artists and how psychologically fragile we are, the fact is that occupation is not a top predictor for suicide. Yes, we can rattle off a list of women writers who’ve killed themselves and yes, we may conjecture that their status as women in the societies in which they lived contributed to the depressive and desperate state that caused them to do so. But it isn’t the unifying theme.You know what is?How many women wrote beautiful novels and stories and poems and essays and plays and scripts and songs in spite of all the crap they endured.[…]The unifying theme is resilience and faith. The unifying theme is being a warrior and a motherfucker. It is not fragility. It’s strength. It’s nerve. And “if your Nerve, deny you—,” as Emily Dickinson wrote, “go above your Nerve.” Writing is hard for every last one of us — straight white men included. Coal mining is harder. Do you think miners stand around all day talking about how hard it is to mine for coal? They do not. They simply dig.[…]So write, Elissa Bassist. Not like a girl. Not like a boy. Write like a motherfucker.

In this excerpt from her altogether fantastic 2012 conversation with The New York Public Library’s Paul Holdengräber, with Bassist in the audience, Strayed elaborates on the art of motherfuckitude:

But being a motherfucker, it’s a way of life, really… It’s about having strength rather than fragility, resilience, and faith, and nerve, and really leaning hard into work rather than worry and anxiety.[…]I think there are a lot of writers who can’t write, or they think they can’t write… I understand that feeling, I think every writer has wrestled with those anxieties and that self-loathing, and yet ultimately in order to succeed in anything we all have to in essence embrace humility, rather.[…]A lot of people think that to be a motherfucker is to be a person who is the dominant figure. But I actually think that true motherfuckerhood … really has to do with being humble. And it’s only when you can get out of your own ego that you can actually do what is necessary to do — in a relationship, in your professional life, as a parent, in any of those ways. It has to do with humility — doing the work.

Tiny Beautiful Things, it bears repeating, is nothing short of necessary to the liver of modern life. Complement this particular fragment with Dani Shapiro onthe plight of the artist and this evolving archive of celebrated writers’ advice on the craft, including Elmore Leonard’s ten tips on writing, Neil Gaiman’s eight pointers, Nietzsche’s ten rules, Walter Benjamin’s thirteen doctrines, Henry Miller’s eleven commandments, and Kurt Vonnegut’s eight tips for writing with style, Zadie Smith on the two psychologies for writing, and Vladimir Nabokov on the three qualities of a great storyteller.

No comments:

Post a Comment