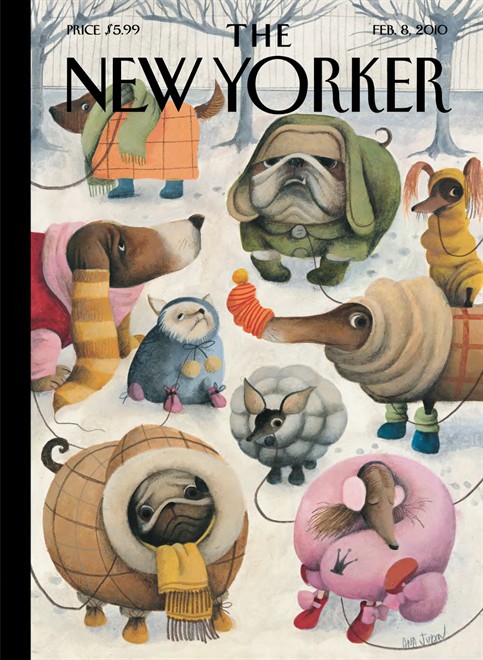

Artwork by Ana Juan from 'The Big New Yorker Book of Dogs.' Click image for more.

Why Not to Put a Raincoat on Your Dog: A Cognitive Scientist Explains the Canine Umwelt

by Maria Popova

“If we want to understand the life of any animal, we need to know what things are meaningful to it.”

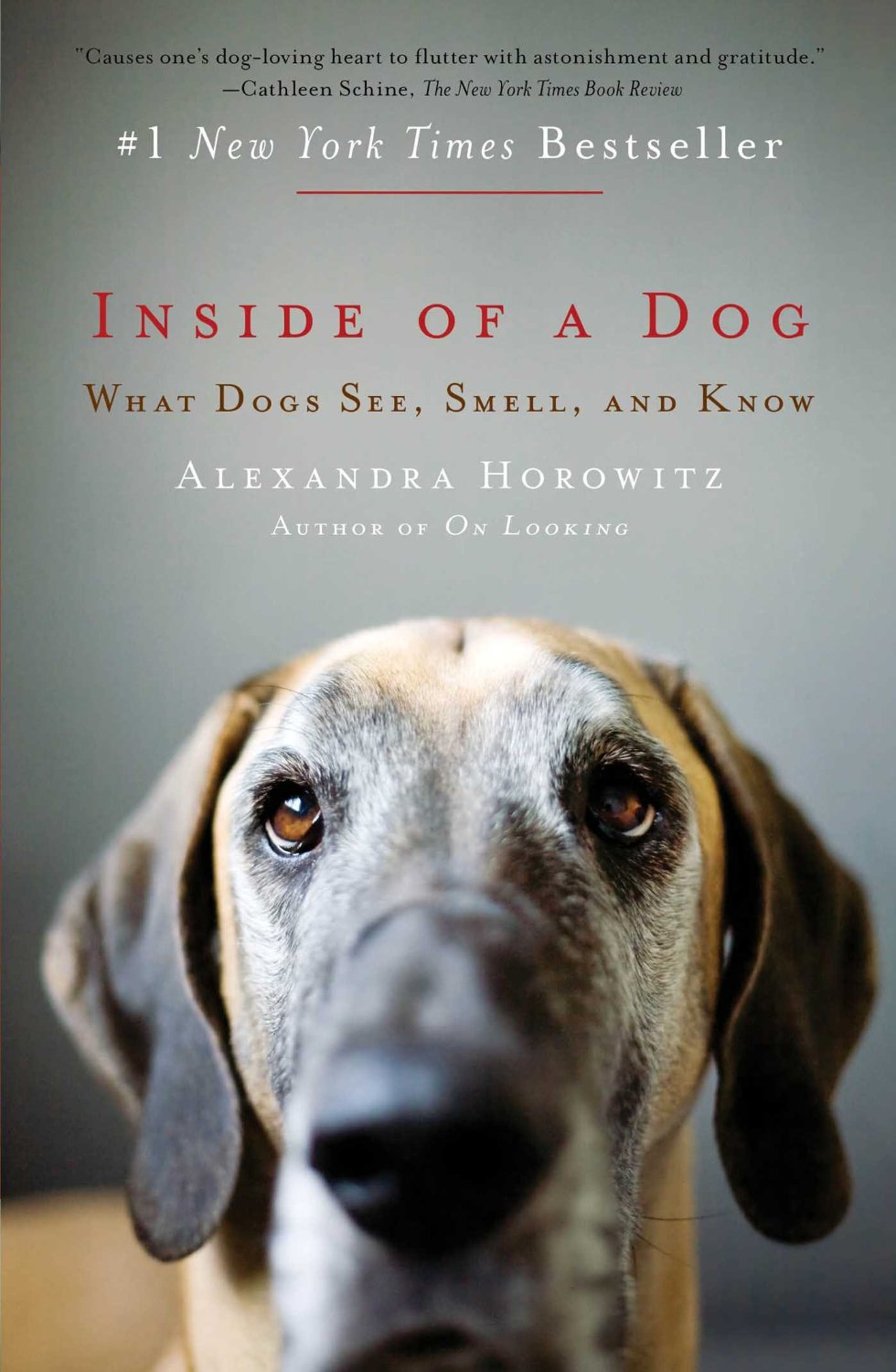

In Anna Karenina, Tolstoy’s Levin observes his dog Laska one evening — “she opened her mouth a little, smacked her lips, and settling her sticky lips more comfortably about her old teeth, she sank into blissful repose” — and finds in her behavior a “token of all now being well and satisfactory,” mirroring the “blissful repose” he so desires in his own life. Our tendency to anthropomorphize our faithful canine companions and project on them our own experiences and intentions may have produced some great literature — including Mary Oliver’s sublime Dog Songs and an entire canon of high-brow comics — but it is something against which cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitzadmonishes with great elegance and rigor in Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know (public library).

In Anna Karenina, Tolstoy’s Levin observes his dog Laska one evening — “she opened her mouth a little, smacked her lips, and settling her sticky lips more comfortably about her old teeth, she sank into blissful repose” — and finds in her behavior a “token of all now being well and satisfactory,” mirroring the “blissful repose” he so desires in his own life. Our tendency to anthropomorphize our faithful canine companions and project on them our own experiences and intentions may have produced some great literature — including Mary Oliver’s sublime Dog Songs and an entire canon of high-brow comics — but it is something against which cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitzadmonishes with great elegance and rigor in Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know (public library).

Of all the misplaced anthropomorphism we unleash on our dogs, Horowitz — a self-described “dog person” and “lover of dogs,” who also happens to be a scientist heading Barnard’s Dog Cognition Lab, where she studies dogs at play — makes a special, and utterly fascinating, case against the use of doggie raincoats:

There are some interesting assumptions involved in the creation and purchase of tiny, stylish, four-armed rain slickers for dogs. Let’s put aside the question of whether dogs prefer a bright yellow slicker, a tartan pattern, or a raining-cats-and-dogs motif (clearly they prefer the cats and dogs). Many dog owners who dress their dogs in coats have the best intentions: they have noticed, perhaps, that their dog resists going outside when it rains. It seems reasonable to extrapolate from that observation to the conclusion that he dislikes the rain.

But dogs, Horowitz points out, are also masters of mixed signals — your dog might wag his tail excitedly as you put the raincoat on him, or he might cower from the coat and curl his tail between his legs; he might look disheveled after a coatless rainy walk, but then take great joy in shaking off the water vigorously. To discern the dog’s true feelings about that possibly plaid, possibly tartan-patterned raincoat, Horowitz turns to the dog’s evolutionary ancestor:

The natural behavior of related, wild canines proves the most informative about what the dog might think about a raincoat. Both dogs and wolves have, clearly, their own coats permanently affixed. One coat is enough: when it rains, wolves may seek shelter, but they do not cover themselves with natural materials. That does not argue for the need for or interest in raincoats. And besides being a jacket, the raincoat is also one distinctive thing: a close, even pressing, covering of the back, chest, and sometimes the head. There are occasions when wolves get pressed upon the back or head: it is when they are being dominated by another wolf, or scolded by an older wolf or relative. Dominants often pin subordinates down by the snout. This is called muzzle biting, and accounts, perhaps, for why muzzled dogs sometimes seem preternaturally subdued. And a dog who “stands over” another dog is being dominant. The subordinate dog in that arrangement would feel the pressure of the dominant animal on his body. The raincoat might well reproduce that feeling. So the principal experience of wearing a coat is not the experience of feeling protected from wetness; rather, the coat produces the discomfiting feeling that someone higher ranking than you is nearby.This interpretation is borne out by most dogs’ behavior when getting put into a raincoat: they may freeze in place as they are “dominated.” … The be-jacketed dog may cooperate in going out, but not because he has shown he likes the coat; it is because he has been subdued. And he will wind up being less wet, but it is we who care about the planning for that, not the dog. The way around this kind of misstep is to replace our anthropomorphizing instinct with a behavior-reading instinct. In most cases, this is simple: we must ask the dog what he wants. You need only know how to translate his answer.

But more than a mere evolutionary curiosity or reality check for our relationship with our beloved pets, this illustrates the broader solipsism of the Golden Rule in its traditional formulation, which urges us to do unto other human animals as we would like for them to do unto us. Instead, as Karen Armstrong has written in her magnificent treatise on the subject, true compassion requires that we seek to understand others so that we can do unto them what they would like done, rather than treating them by the personal ideals we subscribe to ourselves.

Much of that, whether it comes to a dog’s raincoat or to interpersonal relationships between humans, has to do with understanding the umwelt — the subjective reality in which each creature dwells — and how it shapes the meaning of things for that creature. Horowitz writes:

If we want to understand the life of any animal, we need to know what things are meaningful to it. The first way to discover this is to determine what the animal can perceive: what it can see, hear, smell, or otherwise sense. Only objects that are perceived can have meaning to the animal; the rest are not even noticed, or all look the same… Two components — perception and action — largely define and circumscribe the world for every living thing. All animals have their ownumwelten.[…]Each individual creates his own personal umwelt, full of objects with special meaning to him. You can most clearly see this last fact by letting yourself be led through an unknown city by a native. He will steer you along a path obvious to him, but invisible to you. But the two of you share some things: neither of you is likely to stop and listen to the ultrasonic cry of a nearby bat; neither of you smells what the man passing you had for dinner last night (unless it involved a lot of garlic). We … and every other animal dovetail into our environment: we are bombarded with stimuli, but only a very few are meaningful to us.

This notion is what led Horowitz to follow up Inside of a Dog — which is intensely fascinating in its totality — with On Looking: Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes, a book that profoundly changed my perception of reality. For a sample taste of these first disorienting, then wonderfully reorienting ideas, see my conversation with Horowitz about the art and science of looking.

No comments:

Post a Comment