What's Wrong With Georgia?

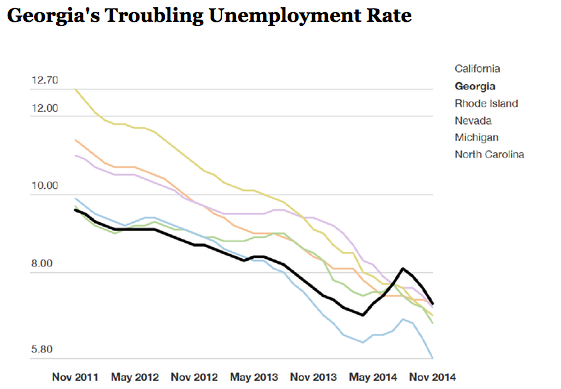

While many other states are recovering, Georgia's unemployment rate has risen. Some blame the state's laissez-faire approach to policy.

GRIFFIN, Ga.—Throughout the economic downturn and subsequent recovery, there have been some usual suspects when it comes to the most pitiful state inmonthly unemployment figures.

For awhile, Michigan took the prize for highest unemployment rate in the country, until Nevada knocked it off its perch in May of 2010. Nevada then held the title for most of the next three years, sometimes sharing the honor with California, until it ceded the top (more accurately, the bottom) spot to Rhode Island in December 2013.

But now, as the economy picks up steam, and consumer sentiment rises to its highest levels since 2007, a new state keeps appearing at the top of the unemployment list. Georgia, home to Fortune 500 heavyweights such as Home Depot, UPS, and Coca-Cola, had the highest unemployment rate in the nation in August, September, and October. With a November rate of 7.2 percent, the state was narrowly edged out by Mississippi’s 7.3 percent (December statistics won’t come out until mid-January).

This may seem surprising, since Georgia was named the best state to do businessin both 2014 and 2013 by Site Selection magazine, largely because of its workforce-training program and low tax rates. Nathan Deal, the state’s GOP governor, handily won re-election in November against Jimmy Carter’s grandson by speaking about Georgia as a job magnet.

But those who follow the state’s economy say the state’s troubling economic figures are directly related to Georgia’s attempts to paint itself as a good state for corporations.

“This is what a state looks like when you have a hands-off, laissez-faire approach to the economy,” said Michael Wald, a former Bureau of Labor Statistics economist in Atlanta. “Georgia is basically a low-wage, low-tax, low-service state, that’s the approach they’ve been taking for a very long time.”

The nation's unemployment rate in November, by contrast, was 5.8 percent, which was also the November jobless rate of Georgia's neighbor and occasional rival, North Carolina.

Governor Deal has emphasized time and again that he believes it is the role of government to get out of the way and let the private sector stimulate the economy. Georgia was among the first states to cut back the duration of unemployment benefits available to its residents to 18 weeks from 26. The state has slashed $8.3 billion from public-school funding since 2003 and passedeligibility requirements for a state financial-aid program that caused a dramatic decline in the number of students in technical colleges (some of those requirements have since been rolled back).

The state also passed a sweeping tax-reform bill in 2012 that eliminated some sales taxes and broadened exemptions for the agricultural industry that small towns and counties say have wreaked havoc on their revenues. Some counties are seeing unemployment rates that indicate the recession is far from over, including Chattahoochee, with an unemployment rate of 14.4 percent and Telfair, with a jobless rate of 13.3 percent.

Areas surrounding Atlanta are faring better, with Fulton County, where Atlanta is located, posting an unemployment rate of 7.3 percent, and DeKalb seeing joblessness drop to 6.8 percent.

But even some areas not far from the city are still struggling. They include the town of Griffin, located in Spalding County, a one-time, textile- manufacturing hub where the unemployment rate in October was 9 percent. Now, workers are tearing down the old factories and shopping plazas along the road from Atlanta are empty, with no trace of the stores once located there.

Griffin residents such as Richard Joiner say they haven't seen much improvement in the economy. Joiner, 46, worked for two decades as a machine operator in the field of plastic extrusion. When he got laid off during the recession, he found a job packing ready-made salads, but then work there slowed down too. Joiner did what economists say workers like him need to do to get ahead in this economy—he went back to school for video and film production, aware that shows such as the Walking Dead were increasinglyfilming and producing in towns like his. But then the state changed the rules for unemployment benefits and Joiner lost his source of income, so he was forced to drop out of school and seek work.

Without any money or prospects, he was evicted from his apartment, so he was forced to move in with his mother. His grown children had to find somewhere else to live. He has no car, so he walks three miles to the Griffin Career Center to search for a job on the computers there.

Joiner still owes $13,000 in student loans, and hasn’t been able to find any sort of work.

“This may be a good place for companies, but not for people actually looking for work,” he told me, sitting in the waiting room of the Career Center. “Companies may come here for the tax breaks, but they’re not actually bringing jobs for the people who live here.”

What’s frustrating about Joiner’s situation is that he’s doing everything right—going back to school, trying a new industry, looking for work wherever he can find it. But without the resources that have long been in place for people like him, he’s struggling.

No comments:

Post a Comment