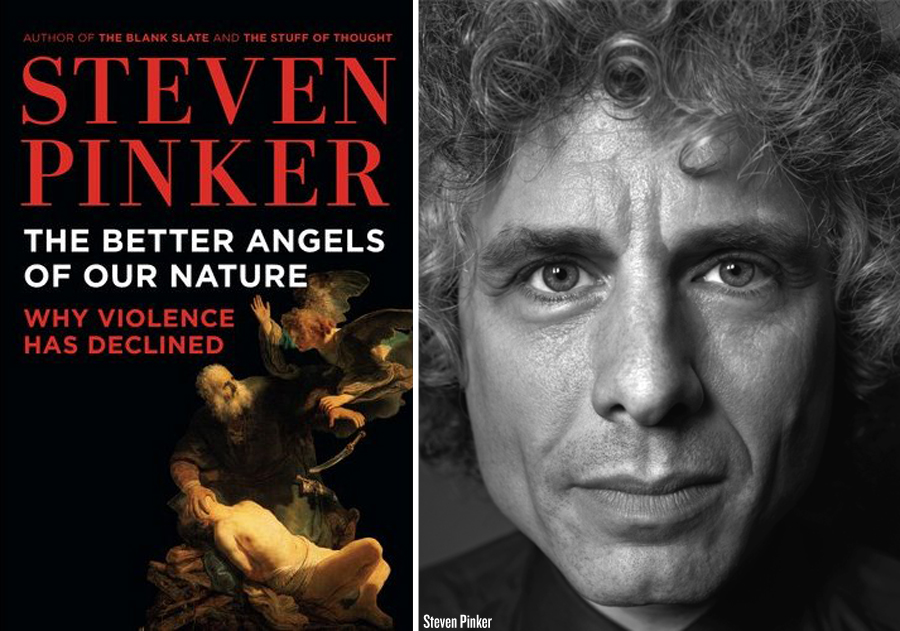

Harvard's Steve Pinker Notes Slight Uptick In Violence In A Much More Peaceful World

The Better Angels of Our Nature

The phrase "the better angels of our nature" stems from the last words of US president Lincoln's first inaugural address. Pinker uses the phrase as a metaphor for four human motivations that, he writes, can "orient us away from violence and towards cooperation and altruism,"[2] namely: empathy, self-control, the "moral sense," and reason.The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined is a 2011 book by Steven Pinker arguing that violence in the world has declined both in the long run and in the short, and suggests explanations to why this has occurred.[1]

Contents

Thesis

Pinker presents a large amount of data (and statistical analysis thereof) that, he argues, demonstrate that violence has been in decline over millennia and that the present is probably the most peaceful time in the history of the human species. The decline in violence, he argues, is enormous in magnitude, visible on both long and short time scales, and found in many domains, including military conflict, homicide, genocide, torture, criminal justice, treatment of children, homosexuals, animals and racial and ethnic minorities. He stresses that "The decline, to be sure, has not been smooth; it has not brought violence down to zero; and it is not guaranteed to continue."[3]

Pinker argues that the radical declines in violent behavior that he documents do not result from major changes in human biology or cognition. He specifically rejects the view that humans are necessarily violent, and thus have to undergo radical change in order to become more peaceable. However, Pinker also rejects what he regards as the simplistic nature versus nurture argument, which would imply that the radical change must therefore have come purely from external ("nurture") sources. Instead, he argues: "The way to explain the decline of violence is to identify the changes in our cultural and material milieu that have given our peaceable motives the upper hand."[4]

Pinker identifies five "historical forces" that have favored "our peaceable motives” and “have driven the multiple declines in violence.”[2] They are:

- The Leviathan – The rise of the modern nation-state and judiciary "with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force,” which “can defuse the [individual] temptation of exploitative attack, inhibit the impulse for revenge, and circumvent…self-serving biases.”

- Commerce – The rise of “technological progress [allowing] the exchange of goods and services over longer distances and larger groups of trading partners,” so that “other people become more valuable alive than dead” and “are less likely to become targets of demonization and dehumanization”;

- Feminization – Increasing respect for "the interests and values of women.”

- Cosmopolitanism – the rise of forces such as literacy, mobility, and mass media, which “can prompt people to take the perspectives of people unlike themselves and to expand their circle of sympathy to embrace them”;

- The Escalator of Reason – an “intensifying application of knowledge and rationality to human affairs,” which “can force people to recognize the futility of cycles of violence, to ramp down the privileging of their own interests over others’, and to reframe violence as a problem to be solved rather than a contest to be won.”[5]

Outline of the book

The first set of six chapters seeks to demonstrate and to analyze historical trends related to declines of violence on different scales. The next chapter discusses "inner demons" - psychological systems that can lead to violence (Pinker identifies five of them). The next chapter examines "better angels" or "motives" that can incline people away from violence (he identifies four). The following chapter examines historical trends that have led to declines in violence (he identifies five).

Six trends (Chapters 2 through 7)

Pinker writes: "To give some coherence to the many developments that make up our species' retreat from violence, I group them into six major trends", namely:

- The Pacification Process – Pinker describes this as the transition from "the anarchy of hunting, gathering, and horticultural societies … to the first agricultural civilizations with cities and governments, beginning around five thousand years ago" which brought "a reduction in the chronic raiding and feuding that characterized life in a state of nature and a more or less fivefold decrease in rates of violent death."[6]

- The Civilizing Process – Pinker argues that "between the late Middle Ages and the 20th century, European countries saw a tenfold-to-fiftyfold decline in their rates of homicide". Pinker attributes the idea of the Civilizing Process to the sociologist Norbert Elias, who "attributed this surprising decline to the consolidation of a patchwork of feudal territories into large kingdoms with centralized authority and an infrastructure on commerce".[6]

- The Humanitarian Revolution – Pinker attributes this term and concept to the historian Lynn Hunt. He says this revolution "unfolded on the [shorter] scale of centuries and took off around the time of the Age of Reason and the European Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries" (though he points to historical antecedents and to "parallels elsewhere in the world"). He writes: "It saw the first organized movements to abolish slavery, dueling, judicial torture, superstitious killing, sadistic punishment, and cruelty to animals, together with the first stirrings of systematic pacifism."[6]

- The Long Peace – a term he attributes to the historian John Lewis Gaddis.[7] This fourth "major transition", Pinker says, "took place after the end of World War II"; in it, he says, "the great powers, and the developed states in general, have stopped waging war on one another".[6]

- The New Peace – Pinker calls this trend "more tenuous", but "since the end of the Cold War in 1989, organized conflicts of all kinds — civil wars, genocides, repression by autocratic governments, and terrorist attacks — have declined throughout the world".[6]

- The Rights Revolutions – The postwar period has seen, Pinker argues, "a growing revulsion against aggression on smaller scales, including violence against ethnic minorities, women, children, homosexuals, and animals. These spin-offs from the concept of human rights—civil rights, women's rights, children's rights, gay rights, and animal rights—were asserted in a cascade of movements from the late 1950s to the present day…".[8]

Five inner demons (Chapter 8)

Here Pinker rejects what he calls the "Hydraulic Theory of Violence" – the idea "that humans harbor an inner drive toward aggression (a death instinct or thirst for blood), which builds up inside us and must periodically be discharged. Nothing could be further from contemporary scientific understanding of the psychology of violence." Instead, he argues, research suggests that "aggression is not a single motive, let alone a mounting urge. It is the output of several psychological systems that differ in their environmental triggers, their internal, their neurological basis, and their social distribution." He examines five such systems:

- Predatory or Practical Violence – violence "deployed as a practical means to an end"[9]

- Dominance – the "urge for authority, prestige, glory, and power"; Pinker argues that dominance motivations can occur within individuals and coalitions of "racial, ethnic, religious, or national groups"[10]

- Revenge – the "moralistic urge toward retribution, punishment, and justice"[11]

- Sadism – the "deliberate infliction of pain for no purpose but to enjoy a person's suffering..."[12]

- Ideology – a "shared belief system, usually involving a vision of utopia, that justifies unlimited violence in pursuit of unlimited good …"[2]

Four better angels (Chapter 9)

Pinker here examines four motives that "can orient [humans] away from violence and towards cooperation and altruism". He identifies:

- Empathy – which "prompts us to feel the pain of others and to align their interests with our own"

- Self-Control – which "allows us to anticipate the consequences of acting on our impulses and to inhibit them accordingly”

- The Moral Sense – which "sanctifies a set of norms and taboos that govern the interactions among people in a culture"; these sometimes decrease violence but can also increase it "when the norms are tribal, authoritarian, or puritanical"

- Reason – which "allows us to extract ourselves from our parochial vantage points"

In this chapter Pinker also examines and rejects the idea that humans have evolved in the biological sense to become less violent.[2]

Influences

Because of the interdisciplinary nature of the book Pinker uses a range of sources from different fields. Particular attention is paid to philosopher Thomas Hobbes who Pinker argues has been undervalued. Pinker's use of 'un-orthodox' thinkers follows directly from his observation that the data on violence contradict our current expectations. In an earlier work Pinker characterised the general misunderstanding concerning Hobbes:

Pinker also references ideas from occasionally overlooked contemporary academics; for example the works of political scientist John Mueller and sociologist Norbert Elias, among others. The extent of Elias' influence on Pinker can be adduced from the title of Chapter 3 of The Better Angels of Our Nature, which is taken from the title of Elias' seminal The Civilizing Process.[14] Pinker also draws upon the work of international relations scholar Joshua Goldstein. They co-wrote a New York Times op-ed article titled 'War Really Is Going Out of Style' that summarises many of their shared views,[15] and appeared together at Harvard's Institute of Politics to answer questions from academics and students concerning their similar thesis.[16]

Reception

Positive

The philosopher Peter Singer positively reviewed The Better Angels of Our Nature in The New York Times.[17] Singer concludes: "[It] is a supremely important book. To have command of so much research, spread across so many different fields, is a masterly achievement. Pinker convincingly demonstrates that there has been a dramatic decline in violence, and he is persuasive about the causes of that decline".[17]

Political scientist Robert Jervis, in a long review for The National Interest, states that Pinker "makes a case that will be hard to refute. The trends are not subtle – many of the changes involve an order of magnitude or more. Even when his explanations do not fully convince, they are serious and well-grounded.".[18]

In a review for The American Scholar, Michael Shermer writes, "Pinker demonstrates that long-term data trumps anecdotes. The idea that we live in an exceptionally violent time is an illusion created by the media’s relentless coverage of violence, coupled with our brain’s evolved propensity to notice and remember recent and emotionally salient events. Pinker’s thesis is that violence of all kinds—from murder, rape, and genocide to the spanking of children to the mistreatment of blacks, women, gays, and animals—has been in decline for centuries as a result of the civilizing process.... Picking up Pinker’s 832-page opus feels daunting, but it’s a page-turner from the start."[19]

In The Guardian, Cambridge University political scientist David Runciman writes, "I am one of those who like to believe that... the world is just as dangerous as it has always been. But Pinker shows that for most people in most ways it has become much less dangerous". Runciman concludes "everyone should read this astonishing book".[20]

In a later review for The Guardian written when the book was shortlisted for the Royal Society Winton Prize for Science Books, Tim Radford wrote, "in its confidence and sweep, the vast timescale, its humane standpoint and its confident world-view, it is something more than a science book: it is an epic history by an optimist who can list his reasons to be cheerful and support them with persuasive instances....I don't know if he's right, but I do think this book is a winner."[21]

Adam Lee writes, in his blog review for Big Think, that "even people who are inclined to reject Pinker's conclusions will sooner or later have to grapple with his arguments".[22]

In a long review in The Wilson Quarterly, psychologist Vaughan Bell calls it "an excellent exploration of how and why violence, aggression, and war have declined markedly, to the point where we live in humanity’s most peaceful age.... powerful, mind changing, and important."[23]

Bill Gates wrote about the book that "Steven Pinker shows us ways we can make those positive trajectories a little more likely. That's a contribution, not just to historical scholarship, but to the world". He considers it one of the most important books he's ever read.[24]

In a long review for the Los Angeles Review of Books, anthropologist Christopher Boehm (Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Southern California and co-director of the USC Jane Goodall Research Center ) called the book "excellent and important"[25]

Political scientist James Q. Wilson, in the Wall Street Journal, called the book "a masterly effort to explain what Mr. Pinker regards as one of the biggest changes in human history: We kill one another less frequently than before. But to give this project its greatest possible effect, he has one more book to write: a briefer account that ties together an argument now presented in 800 pages and that avoids the few topics about which Mr. Pinker has not done careful research." Specifically, the assertions to which Wilson objected were Pinker's writing that (in Wilson's summation), "George W. Bush 'infamously' supported torture; John Kerry was right to think of terrorism as a 'nuisance"; 'Palestinian activist groups' have disavowed violence and now work at building a 'competent government.' Iran will never use its nuclear weapons... [and] Mr. Bush ... is 'unintellectual.' " [26]

Brenda Maddox, in The Telegraph, called the book "utterly convincing" and "well-argued"[27]

The Economist called it "a subtle piece of natural philosophy to rival that of the great thinkers of the Enlightenment. He writes like an angel too."[28] Clive Cookson, reviewing it in the Financial Times, called it "a marvellous synthesis of science, history and storytelling, demonstrating how fortunate the vast majority of us are today to experience serious violence only through the mass media." [29]

The science journalist John Horgan called it "a monumental achievement" that "should make it much harder for pessimists to cling to their gloomy vision of the future" in a largely positive review in Slate Magazine [30]

In The Huffington Post, Neil Boyd, Professor and Associate Director of the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University, strongly defended the book against its critics, saying "While there are a few mixed reviews (James Q. Wilson in the Wall Street Journal comes to mind), virtually everyone else either raves about the book or expresses something close to ad hominem contempt and loathing.... At the heart of the disagreement are competing conceptions of research and scholarship, perhaps epistemology itself. How are we to study violence and to assess whether it has been increasing or decreasing? What analytic tools do we bring to the table? Pinker, sensibly enough chooses to look at the best available evidence regarding the rate of violent death over time, in pre-state societies, in medieval Europe, in the modern era, and always in a global context; he writes about inter-state conflicts, the two world wars, intra-state conflicts, civil wars, and homicides. In doing so, he takes a critical barometer of violence to be the rate of homicide deaths per 100,000 citizens.... Pinker's is a remarkable book, extolling science as a mechanism for understanding issues that are all too often shrouded in unstated moralities, and highly questionable empirical assumptions. Whatever agreements or disagreements may spring from his specifics, the author deserves our respect, gratitude, and applause." [31] Boyd specifically takes to task a number of the book's critics.

The book also saw positive reviews from The Spectator,[32] The Courier-Journal,[33] and The Independent.[34]

Negative

In his review of the book in Scientific American,[35] psychologist Robert Epstein criticizes Pinker's use of relative violent death rates — that is, of violent deaths per capita — as an appropriate metric for assessing the emergence of humanity's "better angels"; instead, Epstein believes that the correct metric is the absolute number of deaths at a given time. (Pinker strongly contests this point; throughout his book, he argues that we can understand the impact of a given number of violent deaths only relative to the total population size of the society in which they occur, and that since the population of the planet has increased by orders of magnitude over history, higher absolute numbers of violent death are certain to occur even if the average individual is far less likely to encounter violence directly in their own lives, as he argues is the case.) Epstein also accuses Pinker of an over-reliance on historical data, and argues that he has fallen prey to confirmation bias, leading him to focus on evidence that supports his thesis while ignoring research that does not.

Several negative reviews have raised criticisms related to Pinker's humanism and atheism.[36] John N. Gray, in a critical review of the book in Prospect, writes, "Pinker's attempt to ground the hope of peace in science is profoundly instructive, for it testifies to our enduring need for faith."[37] New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, while "broadly convinced by the argument that our current era of relative peace reflects a longer term trend away from violence, and broadly impressed by the evidence that Pinker marshals to support this view," offered a list of criticisms and concludes Pinker assumes almost all the progress starts with "the Enlightenment, and all that came before was a long medieval dark."[38] Theologian David Bentley Hart wrote that "one encounters [in Pinker's book] the ecstatic innocence of a faith unsullied by prudent doubt." Furthermore, he says, "it reaffirms the human spirit's lunatic and heroic capacity to believe a beautiful falsehood, not only in excess of the facts, but in resolute defiance of them.",[39] and continues:

Craig S. Lerner, a professor at George Mason University School of Law, in an appreciative but ultimately negative review in the Winter 2011/12 issue of the Claremont Review of Books[40] does not dismiss the claim of declining violence, writing, "...let's grant that the 65 years since World War II really are among the most peaceful in human history, judged by the percentage of the globe wracked by violence and the percentage of the population dying by human hand," but disagrees with Pinker's explanations and concludes that "Pinker depicts a world in which human rights are unanchored by a sense of the sacredness and dignity of human life, but where peace and harmony nonetheless emerge. It is a future — mostly relieved of discord, and freed from an oppressive God — that some would regard as heaven on earth. He is not the first and certainly not the last to entertain hopes disappointed so resolutely by the history of actual human beings." In a sharp exchange in the correspondence section of the Spring 2012 issue, Pinker attributes to Lerner a "theo-conservative agenda" and accuses him of misunderstanding a number of points, notably Pinker's repeated assertion that "historical declines of violence are 'not guaranteed to continue'"; Lerner, in his response, says Pinker's "misunderstanding of my review is evident from the first sentence of his letter" and questions Pinker's objectivity and refusal to "acknowledge the gravity" of issues he raises[41]

Professor emeritus of finance and media analyst Edward S. Herman of the University of Pennsylvania, together with independent journalist David Peterson, wrote detailed negative reviews of the book for theInternational Socialist Review [42] and for Znet [43] concluding "...terrible book, both as a technical work of scholarship and as a moral tract and guide", and describing Pinker as pandering to the "demands of U.S. and Western elites at the start of the 21st century".

Two critical reviews have been related to postmodern approaches. Elizabeth Kolbert wrote a critical review in The New Yorker,[44] to which Pinker posted a reply.[45] Kolbert states that "The scope of Pinker's attentions is almost entirely confined to Western Europe"; Pinker replies that his book has sections on “Violence Around the World," “Violence in These United States," and the history of war in the Ottoman Empire, Russia, Japan, and China. Kolbert states that "Pinker is virtually silent about Europe’s bloody colonial adventures"; Pinker replies that "a quick search would have turned up more than 25 places in which the book discusses colonial conquests, wars, enslavements, and genocides." Kolbert concludes, "Name a force, a trend, or a ‘better angel’ that has tended to reduce the threat, and someone else can name a force, a trend, or an ‘inner demon’ pushing back the other way.” Pinker calls this "the postmodernist sophistry that the The New Yorker so often indulges when reporting on science." An explicitly postmodern critique — or more precisely, one based on perspectivism — is made at CTheory.net by Ben Laws, who argues that "if we take a 'perspectivist' stance in relation to matters of truth would it not be possible to argue the direct inverse of Pinker's historical narrative of violence? Have we in fact become even more violent over time? Each interpretation could invest a certain stake in 'truth' as something fixed and valid — and yet, each view could be considered misguided." Pinker argues in his FAQ page that economic inequality, like other forms of "metaphorical" violence, "may be deplorable, but to lump it together with rape and genocide is to confuse moralization with understanding. Ditto for underpaying workers, undermining cultural traditions, polluting the ecosystem, and other practices that moralists want to stigmatize by metaphorically extending the term violence to them. It's not that these aren't bad things, but you can't write a coherent book on the topic of 'bad things.' ... physical violence is a big enough topic for one book (as the length of Better Angels makes clear). Just as a book on cancer needn't have a chapter on metaphorical cancer, a coherent book on violence can't lump together genocide with catty remarks as if they were a single phenomenon." Quoting this, Laws argues that Pinker suffers from "a reductive vision of what it means to be violent." [46]

John Arquilla of the Naval Postgraduate School criticized the book in a 3 December 2012 article in Foreign Policy for using statistics that he said did not accurately represent the threats of civilians dying in war:

Statistician and philosophical essayist Nassim Taleb coined the term "Pinker Problem" after corresponding with Pinker regarding the theory of great moderation [48] "Pinker doesn’t have a clear idea of the difference between science and journalism, or the one between rigorous empiricism and anecdotal statements. Science is not about making claims about a sample, but using a sample to make general claims and discuss properties that apply outside the sample." [49] In a reply, Pinker denied that his arguments had any similarity to "great moderation" arguments about financial markets, and states that "Taleb’s article implies that Better Angels consists of 700 pages of fancy statistical extrapolations which lead to the conclusion that violent catastrophes have become impossible... [but] the statistics in the book are modest and almost completely descriptive" and "the book explicitly, adamantly, and repeatedly denies that major violent shocks cannot happen in the future."[50]

Stephen Corry, director of the charity Survival International, criticized the book from the perspective of indigenous people's rights. He asserts that Pinker's book "promotes a fictitious, colonialist image of a backward 'Brutal Savage', which pushes the debate on tribal peoples' rights back over a century and [which] is still used to justify their destruction."[51]

In an extensive review of Jared Diamond's The World Until Yesterday, Anthropologist James C. Scott also mentions and attacks Pinker's The Better Angels of Our Nature. Summarizing the conclusions of both books as follows, "we know, on the basis of certain contemporary hunter-gatherers, that our ancestors were violent and homicidal and that they have only recently (very recently in Pinker’s account) been pacified and civilised by the state. Life without the state is nasty, brutish and short." Scott argues, in attacking Diamond and Pinker alike, that "it does not follow that the state, by curtailing ‘private’ violence, reduces the total amount of violence." Also believing that Pinker and Diamond are representing Hobbesian views on the formation of states, "Hobbes’s fable at least has nominally equal contractants agreeing to establish a sovereign for their mutual safety. That is hard to reconcile with the fact that all ancient states without exception were slave states." He also goes to describe various methods stateless societies used in curtailing violence and resolving feuds, and addresses a range of claims made by Diamond which similarly appear in Pinker's work.[52]

Awards and honors

- 2011 New York Times Notable Books of 2011[53]

- 2012 Samuel Johnson Prize, shortlist[54]

- 2012 Royal Society Winton Prize for Science Books, shortlist[55]

- 2013 University of Edinburgh: appointment of Pinker to lectureship on the topic in its series of Gifford Lectures [56]

Media

- Pinker delivering the 2013 Gifford Lecture at the University of Edinburgh [57]

- Pinker discusses The Better Angels of Our Nature with psychologist Paul Bloom on bloggingheads.tv, December 8, 2012[58]

- Pinker debates why violence has declined with Economist Judith Marquand, BHA Chief Executive Andrew Copson and BBC broadcaster Roger Bolton at the Institute of Art and Ideas[59]

No comments:

Post a Comment