The Failed Attempt to Destroy GPS

An axe attack in the early 1990s damaged the same network of satellites that helps you map directions today.

They were arrested and faced up to 10 years in prison for destroying federal government property, causing an estimated $2 million in damage. Ultimately, Kjoller and Lumsdaine took guilty pleas and were sentenced to 18 months and two years in prison respectively for an act of civil disobedience they named "The Harriet Tubman-Sarah Connor Brigade."

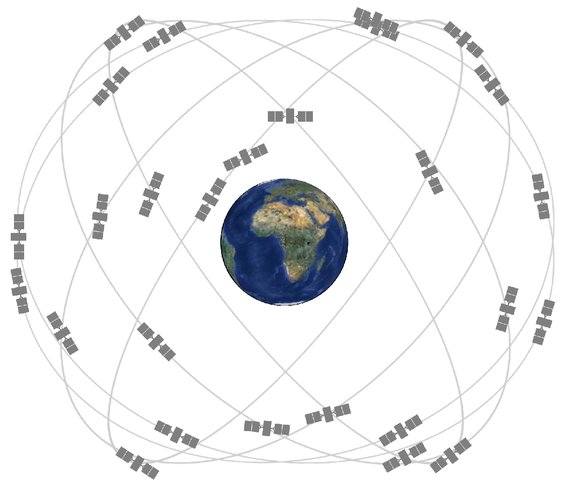

Acting in a tradition of civil disobedience established by the Plowshares movement while citing the leader of the Underground Railroad and the heroine of the Terminator series, the Brigade's target was the Navigation Satellite Timing And Ranging (NAVSTAR) Program and the Global Positioning System (GPS). Back then, GPS was still a fairly obscure and incomplete military technology, used in some civilian applications (the first civilian GPS device, the Magellan NAV 1000, came on the market in 1988) but far from a mainstream resource. Today, GPS feels almost more intimate than industrial or weaponized.

I tend to look at GPS mostly when I'm looking at myself. Or more precisely, formyself, rendered as a small blue dot on a map on my phone. Generally while doing this, I don't pause to consider how that blue dot on a screen is a function of at network of multi-million-dollar satellites in space sending signals to and receiving signals from my phone (yes, in addition to signals from local wi-fi devices and cell towers, but still: Giant machines in space talk to a tiny phone and that is totally normal and expected). It’s easy to take our machines of loving gracefor granted when we experience them mostly as blue dots on tiny screens.

Twenty-three years ago, the Harriet Tubman-Sarah Connor Brigade was thinking about personal relationships to GPS, but more in the context of civilians killed by precision warfare and a population threatened by a growing first-strike nuclear capability. All of this is GPS' provenance. It’s a provenance easily forgotten given its far-reaching influence and impact—not just on navigation but on networks and on networked time. While the Brigade couldn't foresee GPS' temporal impact, their actions are a small but resonant moment in its history, and a reminder of how we neglect technology’s ambivalent histories at our own risk.

* * *

NAVSTAR, the Department of Defense program initiated in 1973 responsible for constructing GPS, was originally called the Defense Navigation Satellite System (DNSS) and emerged from work by the Naval Research Laboratory and the Air Force. In addition to using the system for precise missile targeting and military navigation, GPS satellites were equipped with sensors for detecting nuclear detonations around the world starting around 1980. The NAVSTAR architects always foresaw and planned for civilian applications. Initially, civilians had access to Selective Availability, a deliberately distorted and less precise GPS signal. Industries like shipping and aviation were given access to unjammed GPS in the mid-1990s. In 2000, Selective Availability was disabled and from that point on, anyone with a GPS receiver could get location data as precise as the data used for military and missile navigation.

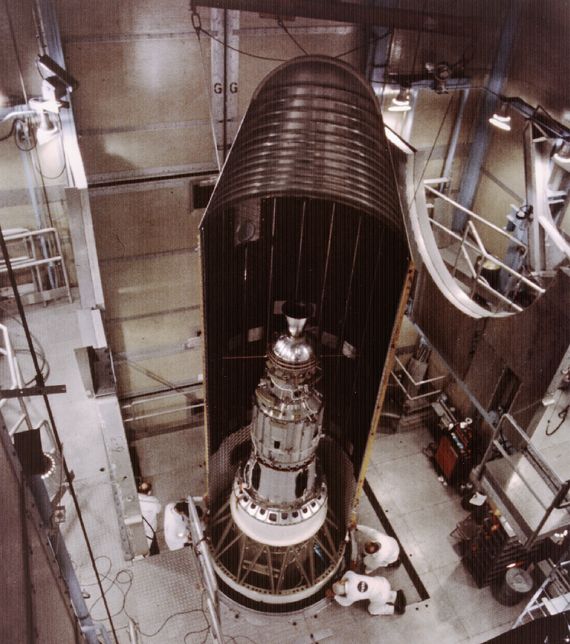

GPS' major media debut took place on the battlefield during the 1991 Gulf War, where GPS-guided cruise missiles took out Iraqi infrastructure and soldiers carried commercial GPS receivers (the system was still incomplete in 1991, and as a result all GPS operations during the Gulf War had to be coordinated within specific time windows to be sure there were enough satellites overhead). When explaining the Gulf War's influence on the Brigade, Lumsdaine noted that "most of the civilian casualties of Operation Desert Storm came after the war because the infrastructure was targeted; the water, the electric lines, the generating stations. GPS was critical for taking out the electric grid of Iraq… with the electricity came repercussions with water filtration plans and so forth." Crippling infrastructure is a long-term attack strategy, and GPS let the military enact it with ruthless precision.

* * *

Understanding how GPS shapes time requires a detour into the concept of navigation itself. Historically, navigation has always been tied to synchronizing time across distance. For a person to know where she was, she needed to reconcile when she was against a when somewhere else—if it's midnight and Constellation X is 45 degrees off from its position in City Y, she could determine the distance traveled from City Y. For much of the 20th century, City Y was usually Greenwich, England, home to Greenwich Mean Time. In 1972, Greenwich Mean Time was replaced with the formal adoption by the International Telecommunications Union of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which determined time using a collection of distributed atomic clocks. Atomic clocks were already being used in experimental satellite projects prior to the creation of the NAVSTAR program, and all GPS satellites rely on atomic clocks to triangulate location. GPS still functions in a similar way to navigation systems of the past, but time has been abstracted away from the position of stars and down to oscillating atoms instead.Synchronized time across distance is a dilemma for communication networks as well as navigation systems. All of the seemingly instantaneous services of the internet require timestamps, and figuring out the when of the network depends on a service we mostly know for giving a where to our networked lives. While almost all networked devices have a real-time clock that internally keeps track of time, when that device connects to a network it usually syncs with a time server using the Network Time Protocol (NTP). All time servers rely on a reference clock, a device or source for the most accurate current time. The type of reference clock used can vary (atomic clocks, radio waves), but GPS receivers are one of the commonly used reference-clock sources because of the system's ubiquity and reliability. No real-time without real-space, and vice versa.

I'm not sure I agree with Lumsdaine's interpretation, but those would probably be the most resonant themes to an anti-nuclear activist watching Terminator 2just after the fall of the Soviet Union. The Harriet Tubman-Sarah Connor Brigade didn't seek to free us from the shackles of accelerated time. Still, there is something poetic about how often civil disobedience takes the form of a demand to slow things down, be it traffic on a highway, labor in a factory, or access to a server. It's hard to imagine someone taking similarly visceral action against Google data centers today, or even the NSA's infamous Utah Data Center—not only because of the security around those buildings but because an attack on a single node just isn't an effective tactic.

While searching for information about the Brigade online, I came across an archived Usenet thread that reminded me of debates over another technology currently reshaping time, distance, war, and commerce: drones. Contributors to the thread criticized the Brigade for overemphasizing GPS' military origins and being unable to conceive of the technology as neutral, if not ultimately “for good.” As the FAA introduces proposals for civilian drone policies and industry associations aggressively distance commercial drones from the drones used for targeted killing, the discourse around the future of unmanned systems is similarly contemptuous of any critique that acknowledges the existence of unethical applications.

What Lumsdaine describes as resistance might be as easily called living with ethics, but ultimately the call to action for either term is, essentially, to take time. In the rush of a persistent accelerated now, interruptions and challenges to life in real-time are sometimes necessary in order to ask what kind of future we're building.

No comments:

Post a Comment