Westboro Baptist Church

***

Self-Certainty is most intense among religious believers. It is the reason why Pascal observed: "Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction."

***

Thoroughly Conscious Ignorance: How the Power of Not-Knowing Drives Progress and Why Certainty Stymies the Evolution of Knowledge

by Maria Popova

“It’s a wonderful idea: thoroughly conscious ignorance.”

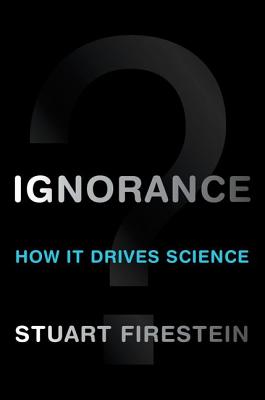

“Allow yourself the uncomfortable luxury of changing your mind,” I reflected in the first of my 7 life lessons from 7 years of Brain Pickings — a notion hardly original and largely essential in life, yet one oh so difficult to adopt and embody. This concept lies at the heart of Stuart Firestein’s excellent book Ignorance: How It Drives Science, one of the best science reads of 2012. In this fantastic TED talk, Firestein, chair of the Department of Biological Sciences at Columbia University and head of the neuroscience lab there, challenges our common attitudes towards knowledge, points out the brokenness of much formal education, and explores what Richard Feynman so poetically advocated — the growth-value of remaining uncertain — in science, and, by extension, in life:

“Allow yourself the uncomfortable luxury of changing your mind,” I reflected in the first of my 7 life lessons from 7 years of Brain Pickings — a notion hardly original and largely essential in life, yet one oh so difficult to adopt and embody. This concept lies at the heart of Stuart Firestein’s excellent book Ignorance: How It Drives Science, one of the best science reads of 2012. In this fantastic TED talk, Firestein, chair of the Department of Biological Sciences at Columbia University and head of the neuroscience lab there, challenges our common attitudes towards knowledge, points out the brokenness of much formal education, and explores what Richard Feynman so poetically advocated — the growth-value of remaining uncertain — in science, and, by extension, in life:Ignorance has a lot of bad connotations [but] I mean a different kind of ignorance. I mean a kind of ignorance that’s less pejorative, a kind of ignorance that comes from a communal gap in our knowledge, something that’s just not there to be known or isn’t known well enough yet or we can’t make predictions from, the kind of ignorance that’s maybe best summed up in a statement by James Clerk Maxwell, perhaps the greatest physicist between Newton and Einstein, who said, “Thoroughly conscious ignorance is the prelude to every real advance in science.” I think it’s a wonderful idea: thoroughly conscious ignorance.[…]So I’d say the model we want to take is not that we start out kind of ignorant and we get some facts together and then we gain knowledge. It’s rather kind of the other way around, really. What do we use this knowledge for? What are we using this collection of facts for? We’re using it to make better ignorance, to come up with, if you will, higher-quality ignorance.

Ignorance remains a must-read. Complement it with Richard Feynman on the universal responsibility of scientists, then see how this mindset manifests in other domains of culture, from poetry to psychology to film.

No comments:

Post a Comment