The Central Appalachian region has been the heart of coal country for as long as anyone can remember. But in recent years, Kentucky and West Virginia's coal industries have been facing a painful decline — and that decline is starting to get widespread attention.

(Ed Reinke/Associated Press)

The House Energy and Commerce Committee held a big hearing last week on how coal communities in the area are suffering, with Republicans blaming Environmental Protection Agency regulations for the damage. In a related vein, our former colleague Suzy Khimm had an in-depth piece for MSNBC looking at eastern Kentucky, which is being hit hard by both the coal industry's decline and sharp budget cuts from sequestration.

It's worth taking a closer look at why, exactly, coal communities in Central Appalachia have suffered so heavily in recent years. Regulations aren't the whole story. The entire U.S. coal industry is under pressure from a variety of forces — from the shale gas boom to coal-plant retirements — and the Appalachian region in particular is getting hurt by trends that have been building for decades.

The decline of Appalachia

First, as Patrick Reis reported over at National Journal, coal jobs in West Virginia and Kentucky have been vanishing for decades — long before Barack Obama became president. So there are some long-term trends at work here:

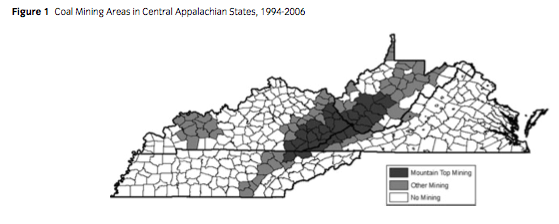

Why have Kentucky and West Virginia lost 38,000 coal jobs since 1983? For one, coal mining has become increasingly automated in recent decades, particularly as companies have shifted to techniques such as mountaintop-removal mining, which are less labor intensive. (An EPA crackdown on mountaintop removal in 2009 actually led to a small bump in coal employment in West Virginia.)

Another big problem for Appalachia's coal industry has been competition from cheaper, low-sulfur coal out West — particularly from Wyoming's Powder River Basin. Here's a good chart from Scientific American's David Wogan showing this shift:

On top of everything else, Central Appalachia's coal now appears to be running out, as many of the thick, easy-to-mine seams have vanished. The Energy Information Administration estimates that coal production in eastern Kentucky and West Virginia will soon be just half of what it was in 2008, plunging from 234 million tons down to 112 million tons in 2015.

Problems in the broader coal industry

And this is all before delving into the pressures that the entire U.S. coal industry is facing. A combination of cheap natural gas from shale fracking and new pollution regulations from the EPA have been elbowing aside coal in the electricity sector.

As a result, one recent report from the Energy Information Administration found that U.S. plant owners and operators are getting ready to retire 27 gigawatts' worth of coal generation, or about 8.5 percent of the coal fleet, between now and 2016:

So far, the coal-mining industry has weathered this storm by exporting more coal abroad, especially to Europe. But the future for coal exports is murky. Environmentalists have protested planned export terminals in the Northwest. And analysts at Goldman Sachs think the overseas market for coal — particularly in China — could stagnate in the years to come.

That means the U.S. coal industry as a whole is facing pressure from a variety of fronts — both regulatory pressures and competition from cheaper sources like natural gas. (There was also the Sierra Club's "Beyond Coal" campaign in the 2000s, which was particularly effective at blocking new coal plants.) Yet Appalachia is particularly vulnerable, in part due to headwinds that have been gathering strength for decades.

The cost of coal's decline

So what does that mean for coal-reliant communities in Central Appalachia and elsewhere? In the short term, nothing good.

While the coal industry directly employs just 21,000 workers in West Virginia, the industry itself added about $5.9 billion to state GDP in 2008 and generated $670 million in taxes — a whopping 15 percent of the state’s budget.

Those funds won’t vanish tomorrow, but they will slowly slip away. A 2010 report by the consulting firm Downstream Strategies noted that coal's decline would lead to sharp decreases in tax revenue for Kentucky and West Virginia. (By contrast, coal production in Northern Appalachia, including parts of Ohio and Pennsylvania, is expected hold steady for years.)

And there will likely be knock-on effects for years to come. As I reported here, many retired miners in Appalachia are getting hurt by the disruptions in the coal industry, as companies file for bankruptcy and try to shed pension and health obligations for retirees. Suzy Khimm's piece details the many ways in which Eastern Kentucky has been ravaged by coal's decline.

Some experts have suggested that Central Appalachia could eventually thrive from shifting away from its single-minded focus on coal. The Downstream Strategies report observes that the region has a wealth of clean-energy resources, from wind to solar to sustainable biomass. West Virginia, for one, is looking to get into shale-gas drilling. Still, it’d be a mistake to gloss over how disruptive — and painful — that transition could be. Just look at Detroit’s struggles in shifting away from its longstanding reliance on the auto industry.

And, so far, the federal government hasn't helped much. Here's a telling line from Suzy's piece: "[Obama] promised in June to 'give special care to people and communities that are unsettled by the transition' to cleaner energy. But so far, little extra help has arrived in eastern Kentucky."

No comments:

Post a Comment