U.S. federal government actions against polygamy

1857–1858 Utah War

Main article: Utah War

As The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints settled in what became the Utah Territory it eventually was subjected to the power and opinion of the United States. Friction first began to show in the James Buchanan administration and federal troops arrived (see Utah War). President Buchannan, anticipating Mormon opposition to a newly appointed governor to replace Brigham Young, dispatched 2,500 federal troops to Utah to seat the new governor, thus setting in motion a series of unfortunate misunderstandings when the Mormons felt threatened in light of their past history.[45]

1862 Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act

Main article: Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act

Further information: Poland Act

The rest of the United States for the most part considered plural marriage offensive. On July 8, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act into law, which forbade the practice in US territories. Lincoln told the church that he had no intentions of enforcing it if they would not interfere with him, and so the matter was laid to rest for a time. But rhetoric continued, and polygamy became an impediment to Utah being admitted to the United States. This was not a concern to Brigham Young, who preached in 1866 that if Utah will not be admitted to the Union until it abandons polygamy, "we shall never be admitted."[46]

After the Civil War, immigrants to Utah who were not members of the church continued the contest for political power. They were frustrated by the consolidation of the members. Forming the Liberal Party, they began pushing for political changes and to weaken the church's advantage in the territory. In September 1871, President Brigham Young was indicted for adultery due to his plural marriages. On January 6, 1879, the Supreme Court upheld the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act in Reynolds v. United States.

1882 Edmunds Act

Main article: Edmunds Act

In February 1882, George Q. Cannon, a prominent leader in the church, was denied a non-voting seat in the House of Representatives due to his polygamous relations. This revived the issue in national politics. One month later, theEdmunds Act was passed by Congress, amending the Morrill Act and made polygamy a felony punishable by a $500 fine and five years in prison. Unlawful cohabitation, where the prosecution did not need to prove that a marriage ceremony had taken place (only that a couple had lived together), was a misdemeanor punishable by a $300 fine and six months imprisonment.[3] It also revoked the right of polygamists to vote or hold office and allowed them to be punished without due process. Even if people did not practice polygamy, they would have their rights revoked if they confessed a belief in it. In August, Rudger Clawson was imprisoned for continuing to cohabit with wives that he married before the 1862 Morrill Act.

1887 Edmunds-Tucker Act

Main article: Edmunds-Tucker Act

In 1887, the Edmunds-Tucker Act allowed the seizure of the church and its property and further extended the punishments of the Edmunds Act of 1882. In July of the same year, the U.S. Attorney General filed suit to seize the church and all of its assets.

The church was losing control of the territorial government, and many members and leaders were being actively pursued as fugitives. Without being able to appear publicly, the leadership was left to navigate underground. Teaching new marriage and family arrangements where the principles that could not be openly discussed, compounded the problems. Those authorized to teach the doctrine had always stressed the strict covenants, obligations and responsibilities associated with it—the antithesis of license. But those who heard only rumors, or who chose to distort and abuse the teaching, often envisioned and sometimes practiced something quite different. One such person was John C. Bennett, an earlier mayor of Nauvoo and adviser to Joseph Smith, who twisted the teaching to his own advantage. Capitalizing on rumors and lack of understanding among general church membership, he taught a doctrine of "spiritual wifery". He and associates sought to have illicit sexual relationships with women by telling them that they were married "spiritually", even if they had never been married formally, and that the Prophet approved the arrangement. These statements were false. The Bennett scandal resulted in his excommunication and the disaffection of several others. Bennett then toured the country speaking against the Latter-day Saints and published a bitter anti-Mormon exposé charging the Saints with licentiousness. Those that twisted teachings of polygamy over the years often caused serious problems and acted as a fuel for distress over the issue, associated rumors, and misunderstandings.

Following the aforementioned passage of the Edmunds-Tucker Act in 1887, the church found it difficult to operate as a viable institution. Among other things, this legislation disincorporated the church, confiscated its properties, and even threatened seizure of its temples. After visiting priesthood leaders in many settlements, President Woodruff left for San Francisco on September 3, 1890, to meet with prominent businessmen and politicians. He returned to Salt Lake City on September 21, determined to obtain divine confirmation to pursue a course that seemed to be agonizingly more and more clear. As he explained to church members a year later, the choice was between, on the one hand, continuing to practice plural marriage and thereby losing the temples, "stopping all the ordinances therein," and, on the other, ceasing plural marriage in order to continue performing the essential ordinances for the living and the dead. President Woodruff hastened to add that he had acted only as the Lord directed:

I should have let all the temples go out of our hands; I should have gone to prison myself, and let every other man go there, had not the God of heaven commanded me to do what I do; and when the hour came that I was commanded to do that, it was all clear to me.[47]

1890 Manifesto banning plural marriage

Main article: 1890 Manifesto

The final element in President Woodruff's revelatory experience came on the evening of September 23, 1890. The following morning, he reported to some of the General Authorities that he had struggled throughout the night with the Lord regarding the path that should be pursued. The result was a 510-word handwritten manuscript which stated his intentions to comply with the law and denied that the church continued to solemnize or condone plural marriages. The document was later edited by George Q. Cannon of the First Presidency and others to its present 356 words. On October 6, 1890, it was presented to the Latter-day Saints at the General Conference and approved.

While many church leaders in 1890 regarded the Manifesto as inspired, there were differences among them about its scope and permanence. Some leaders were reluctant to terminate a long-standing practice that was regarded as divinely mandated. As a result, over 200 plural marriages were performed between 1890 and 1904.[48]

1904 second manifesto banning plural marriage

Main article: Second Manifesto

It was not until 1904, under the leadership of President Joseph F. Smith, that the church completely banned new plural marriages worldwide.[49] Not surprisingly, rumors persisted of marriages performed after the 1890 manifesto, and beginning in January 1904, testimony given in the Smoot hearings made it clear that plural marriage had not been completely extinguished.

The ambiguity was ended in the General Conference of April 1904, when President Joseph F. Smith issued the "Second Manifesto", an emphatic declaration that prohibited plural marriage and proclaimed that offenders would be subject to church discipline. They declared that any who participated in additional plural marriages, and those officiating, would be excommunicated from the church. Those disagreeing with the second manifesto included apostles Matthias F. Cowley and John W. Taylor who both resigned from the Quorum of the Twelve. Cowley retained his membership in the church, but Taylor was later excommunicated.

Although the 1904 Manifesto ended the official practice of new plural marriages, existing plural marriages were not automatically dissolved. Many Mormons, including prominent church leaders, maintained existing plural marriages well into the 20th century.

In 1943, the First Presidency discovered apostle Richard R. Lyman was cohabitating with a woman other than his legal wife. As it turned out, in 1925 Lyman had begun a relationship which he defined as a polygamous marriage. Unable to trust anyone else to officiate, Elder Lyman and the woman exchanged vows secretly. By 1943, both were in their seventies. Lyman was excommunicated on November 12, 1943 at age 73. The Quorum of the Twelve provided the newspapers with a one-sentence announcement, stating that the ground for excommunication was violation of the Law of Chastity, which any practice of post-Manifesto polygamy constituted.

Remnants within sects

Over time, many of those who rejected the LDS Church's relinquishment of plural marriage formed small, close-knit communities in areas of the Rocky Mountains. These groups continue to practice 'the principle' despite the opposition. These people are commonly called Mormon fundamentalists and may either practice as individuals, as families, or as part of organized denominations. The official style guide of the church objects to the use of the term "Mormon fundamentalists" and suggests using the term "polygamist sects" to avoid confusion about whether the main body of Mormon believers teach or practice polygamy. [4]

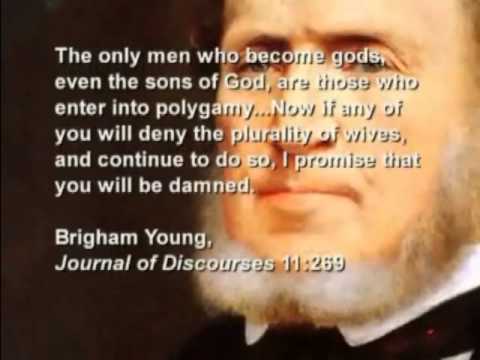

Members of these polygamist sects believe that plural marriage is a requirement for exaltation and entry into the highest "degree" of the Celestial kingdom (the highest of three Mormon heavens). This belief stems from statements by 19th century Mormon authorities including Brigham Young, although some of these leaders gave possibly conflicting statements that a monogamist may obtain at least a lower degree of "exaltation" through mere belief in polygamy.[51] Thus, plural marriage is viewed as an essential and fundamental part of the religion.

For public relations reasons, the LDS Church has sought vigorously to disassociate itself from Mormon fundamentalists and the practice of plural marriage.[52] Although the LDS Church has requested that journalists not refer to Mormon fundamentalists using the term Mormon,[53] journalists generally have not complied, and Mormon fundamentalist has become standard terminology. Mormon fundamentalists themselves embrace the term Mormon, and share a common religious heritage with the LDS Church including canonization of the Book of Mormon.

Modern plural marriage theory within the LDS Church

Although the LDS Church has abandoned the practice of plural marriage, it has not abandoned the underlying doctrines of polygamy in an eternal sense. According to the church's sacred texts and pronouncements by its leaders and theologians, the church leaves open the possibility that it may one day re-institute the practice. It is the practice of Mormons to seal themselves to their wives. Inasmuch as a man, unlike a woman, may be sealed to multiple, sequential wives on earth, it is possible for a man to have multiple wives in the Celestial Kingdom.[citation needed] A deceased woman may, however, be vicariously sealed to each of her past husbands[54].

[edit]LDS reasons for allowing polygamy

As early as the publication of the Book of Mormon in 1830, LDS doctrine maintained that polygamy was allowable so long as it was commanded by God. The Book of Jacob condemned polygamy as adultery,[55] but left open the proviso that "For if I will, saith the Lord of Hosts, raise up seed unto me, I will command my people; otherwise, they shall hearken unto these things."[56] Thus, the LDS Church today teaches that plural marriage can only be practiced when specifically authorized by God. According to this view, the 1890 Manifesto and/or 1904 Manifesto rescinded God's prior authorization given to Joseph Smith.

However, Bruce R. McConkie stated in his controversial 1958 book, Mormon Doctrine, that God will "obviously" re-institute the practice of polygamy after the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.[57] This echoes earlier teachings by Brigham Young that the primary purpose of polygamy was to bring about the Millennium.[58] Current official church teaching materials do not make any mention of the future re-institution of plural marriage.

Miles Park Romney (Gray haired man in middle)

Mitt Romney's polygamous great-great grandfather

No comments:

Post a Comment