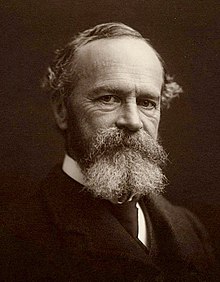

William

James

***

Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library

Excerpt: Lecture I "Religion and Neurology"

There can be no doubt that as a matter of fact a religious life, exclusively pursued, does tend to make the person exceptional and eccentric. I speak not now of your ordinary religious believer, who follows the conventional observances

of his country, whether it be Buddhist, Christian, or Mohammedan. His religion has been made for him by others, communicated to him by tradition, determined to fixed forms by imitation, and retained by habit. It would profit us little to study this second-hand religious life. We must make search rather for the original experiences which were the pattern-setters to all this mass of suggested feeling and imitated conduct. These experiences we can only find in individuals for whom religion exists not as a dull habit, but as an acute fever rather. But such individuals are "geniuses" in the religious line; and like many other geniuses who have brought forth fruits effective enough for commemoration in the pages of biography, such religious geniuses have often shown symptoms of nervous instability. Even more perhaps than other kinds of genius, religious leaders have been subject to abnormal psychical visitations. Invariably they have been creatures of exalted emotional sensibility. Often they have led a discordant inner life, and had melancholy during a part of their career. They have known no measure, been liable to obsessions and fixed ideas; and frequently they have fallen into trances, heard voices, seen visions, and presented all sorts of peculiarities which are ordinarily classed as pathological. Often, moreover, these pathological features in their career have helped to give them their religious authority and influence.

If you ask for a concrete example, there can be no better one than is furnished by the person of George Fox. The Quaker religion which he founded is something which it is impossible to overpraise. In a day of shams, it was a religion of veracity rooted in spiritual inwardness, and a return to something more like the original gospel truth than men had ever known in England. So far as our Christian sects today are evolving into liberality, they are simply reverting in essence to the position which Fox and the early Quakers so long ago assumed. No one can pretend for a moment that

in point of spiritual sagacity and capacity, Fox's mind was unsound. Everyone who confronted him personally, from Oliver Cromwell down to county magistrates and jailers, seems to have acknowledged his superior power. Yet from the point of view of his nervous constitution, Fox was a psychopath or détraqué of the deepest dye. His Journal abounds in entries of this sort: --

"As I was walking with several friends, I lifted up my head and saw three steeple-house spires, and they struck at my life. I asked them what place that was? They said, Lichfield. Immediately the word of the Lord came to me, that I must go thither. Being come to the house we were going to, I wished the friends to walk into the house, saying nothing to them of whither I was to go. As soon as they were gone I stept away, and went by my eye over hedge and ditch till I came within a mile of Lichfield where, in a great field, shepherds were keeping their sheep. Then was I commanded by the Lord to pull off my shoes. I stood still, for it was winter: but the word of the Lord was like a fire in me. So I put off my shoes and left them with the shepherds; and the poor shepherds trembled, and were astonished. Then I walked on about a mile, and as soon as I was got within the city, the word of the Lord came to me again, saying: Cry, 'Wo to the bloody city of Lichfield!' So I went up and down the streets, crying with a loud voice, Wo to the bloody city of Lichfield! It being market day, I went into the market-place, and to and fro in the several parts of it, and made stands, crying as before, Wo to the bloody city of Lichfield! And no one laid hands on me. As I went thus crying through the streets, there seemed to me to be a channel of blood running down the streets, and the market-place appeared like a pool of blood. When I had declared what was upon me, and felt myself clear, I went out of the town in peace; and returning to the shepherds gave them some money, and took my shoes of them again. But the fire of the Lord was so on my feet, and all over me, that I did not matter to put on my shoes again, and was at a stand whether I should or no, till I felt freedom from the Lord so to do: then, after I had washed my feet, I put on my shoes again.

After this a deep consideration came upon me, for what reason I should be sent to cry against that city, and call it The bloody city! For though the parliament had the minister one while, and the king another, and much blood had been shed in the town during the wars between them, yet there was no more than had befallen many other places. But afterwards I came to understand, that in the Emperor Diocletian's time a thousand Christians were martyr'd in Lichfield. So I was to go, without my shoes, through the channel of their blood, and into the pool of their blood in the market-place, that I might raise up the memorial of the blood of those martyrs, which had been shed above a thousand years before, and lay cold in their streets. So the sense of this blood was upon me, and I obeyed the word of the Lord."

Bent as we are on studying religion's existential conditions, we cannot possibly ignore these pathological aspects of the subject. We must describe and name them just as if they occurred in non-religious men. It is true that we instinctively recoil from seeing an object to which our emotions and affections are committed handled by the intellect as any other object is handled. The first thing the intellect does with an object is to class it along with something else. But any object that is infinitely important to us and awakens our devotion feels to us also as if it must be sui generis and unique. Probably a crab would be filled with a sense of personal outrage if it could hear us class it without ado or apology as a crustacean, and thus dispose of it. "I am no such thing, it would say; I am MYSELF, MYSELF alone.

Alan: The very variety of religious experience -- and each sectarian's insistence that he is right and others wrong (more often than not, 'damnably wrong') -- suggests our need to honor variety (while finding the "spiritual technology" that best suits us) without insisting on the self-righteous singularity that lies behind Pascal's horror: "Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction." This separation of wheat from chaff summarizes the work ahead. We have not, as many think, outgrown religion. This is work that must be done for religion (or spirituality if you must...) is, as Jung observed, humankind's fundamental instinct. We are here to revere. And out of this essential reverence flows The Good. The question is this: Can we humbly affirm everyone's inevitably "personal" God without indulging the self-validating degradation of others?

***

Alan: The very variety of religious experience -- and each sectarian's insistence that he is right and others wrong (more often than not, 'damnably wrong') -- suggests our need to honor variety (while finding the "spiritual technology" that best suits us) without insisting on the self-righteous singularity that lies behind Pascal's horror: "Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction." This separation of wheat from chaff summarizes the work ahead. We have not, as many think, outgrown religion. This is work that must be done for religion (or spirituality if you must...) is, as Jung observed, humankind's fundamental instinct. We are here to revere. And out of this essential reverence flows The Good. The question is this: Can we humbly affirm everyone's inevitably "personal" God without indulging the self-validating degradation of others?

"The impasse contained in the scientific viewpoint itself can only be broken through by the attainment of a view of nothingness which goes further than, which transcends the nihil of nihilism. The basic Buddhist insight of Sunyata, usually translated as "emptiness," "the void," or "no-Thingness," that transcends this nihil, offers a viewpoint that has no equivalent in Western thought. The consciousness of the scientist, in his mechanized, dead and dumb universe, logically reaches the point where --- if he practices his science existentially and not merely intellectually -- the meaning of his own existence becomes an absurdity and he stands on the rim of the abyss of nihil face to face with his own nothingness. People are not aware of this dilemma. That it does not cause great concern is in itself a symptom of the sub-marine earthquake of which our most desperate world-problems are merely symptomatic... It is becoming ever clearer that the terrors of war, hunger and despoliation are neither economic, nor technological problems for which there are economic or technological solutions. They are primarily spiritual problems..." Frederick Franck

Frederick Franck was born into a non-observant Jewish family in Holland. He was subsequently baptized a Protestant. After graduating as a dentist, Franck began the first dental clinic at Albert Schweitzer's hospital in West Africa. Later, having embarked a career as writer and artist, Mr. Franck heeded Pope John XXIII's call to build a society of peace on earth (Pacem in Terris.) Franck became the official artist of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) and, as a tribute to Pope John, has created a temple of all faiths called Pacem in Terris on his property in Warwick, New York. (The full text of John XXIII's encyclical, Pacem in Terris, is available at http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_xxiii/encyclicals/documents/hf_j-xxiii_enc_11041963_pacem_en.html

***

No comments:

Post a Comment