Well, for one thing, settlers and pioneers heading westward didn’t routinely use horses to pull their wagons. Horses, while wonderful dray animals for carriages and coaches, were very poor animals for pulling heavy wagons. They played out quickly, required a great deal of fodder, and were prone to injury. The beast of burden of choice was the ox. The ox had the advantage, also, of being put into service pulling a plow or helping out with other heavy labor required to build and establish a homestead. A team of two, four, or even six oxen was pretty much a requirement. Lighter wagons could be drawn by mules and mule teams. A mule is generally stronger and more durable than a horse as a draft animal; it’s also sure-footed and more easily worked, and additionally can serve as a reliable labor animal on a settler’s new home.

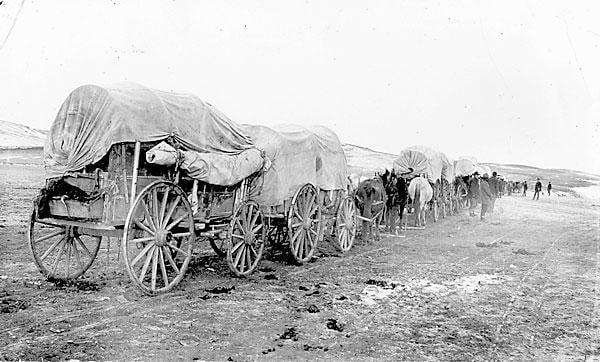

It’s important to bear in mind, also, that most of the settlers moving westward were agrarians, farmers for the most part, and the economical and reliable choice of working animals would have demanded strong, durable, and reliable animals that had versatility. Dogs and cats were commonly included. Certainly, many owned horses, and some of these were broken to harness, but a Conestoga or even a Studebaker wagon, the two most common types of conveyance on the frontier, fully loaded with all of a family’s earthly possessions as well as the family themselves, could weigh up to two tons or more. The strength of an ox was desirable.

Traversing the frontier was no easy matter. Although the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails were well marked, not everyone followed those routes as the century developed. The endless flat plains, which were poorly mapped or explored, were crisscrossed with rivers, creeks, runs, gorges and rocky outcroppings that would have been difficult or impossible for a wagon to traverse. Broad waterways sometimes required the construction of rafts if the depth was too great to ford. Most wagon trains employed at least one scout to move out ahead of the trail to identify impediments and to discover a way around them, if crossing them proved too difficult or time-delaying to manage. A two or three-day delay because of a detour would not have been uncommon. Crossing mountain ranges, especially the Rockies or the Sierras posed formidable challenges, as well, not only because of the roughness of the terrain but also because of the altitude, which could have negative effects on draft animals as well as people. Again, scouts, supposedly familiar with previous explorers and trail-blazers, attempted to direct settlers to mountain passes and detouring routes when obstacles proved too difficult to cross.

Movement across the frontier was slow. On a good day, even a short and efficient train could make about fifteen miles. Weather, break-downs, illness or, as described, various obstacles could limit that even more. There are records indicating that some wagon trains, especially in the 1850s when the quality of wagons was not as high as in later eras, only made two or three miles a day on average. But there are others that sometimes made as much as twenty or twenty-five. A broken axle or wheel, though, could cause a delay, as could the need to stop and replenish water and food. Many trains had “foragers,” whose job it was to hunt game as the train proceeded. Otherwise, settlers had to rely on whatever food supplies they could carry with them, largely cured pork (bacon, for the most part), dried beans and other vegetables, cornmeal, and, if they were particularly prosperous, flour. If possible, they might find wild onions or asparagus or other edible vegetables as they progressed; fruit other than berries and persimmons and plums, pecans and walnuts were discoverable in certain areas at certain times of the year. Most tried to bring along edible and/or productive fowl, such as chickens or ducks or geese, to provide both eggs and meat for the journey. If they encountered creeks and rivers, of course, they could fish, if they had the time.

Weather was a greater concern than geography, though. Most settlers embarked for the farthest reaches of the West (Oregon, California, etc.) in the early spring, setting off from Missouri or Iowa, generally. Late spring blizzards and violent spring storms were frequently encountered; as the season warmed into summer, oppressive heat, swarms of insects, venomous reptiles, large and vicious predatory animals such as wolves, mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, etc. plagued livestock and even small children. Prior to the 1870s, massive buffalo herds might block a train’s progress for days while the animals passed in their never-ending quest for grazing. The main worry of settlers was their need to complete their journeys before the freezing temperatures of winter came; sometimes they were unsuccessful when the seasons changed earlier than expected or when delays pushed them deeper and deeper into the year.

Illness, injury, and disease were also problems. Antibiotics and antiseptics, other than raw alcohol were unknown, and the only pain-killers they knew were opium, generally mixed with alcohol and highly addictive, so settlers relied mostly on whatever remedies they already knew or were at hand. A scratch, though, could develop into a serious infection or lockjaw; gangrene was a constant concern; illnesses such as fevers and stomach viruses could spread through a whole train. A great fear was of diseases such as smallpox, cholera, malaria, yellow fever, etc., which if identified in an individual wagon or family might result in them being exiled from the rest of the train, effectively quarantined, or even left behind on their own. Whatever medicines or remedies they had available were only those they could carry with them. Trains did not routinely employ physicians of any kind.

Bandits and depredating hostiles were also a fear. Being totally isolated from news or contact with civilization, settlers were ignorant of sudden uprisings or reports of attacks from any threatening groups or gangs. They had to rely on themselves for defense, and being proficient with a weapon, particularly a rifle, was a virtual requirement. Wagon masters (usually employed for any substantial train) and scouts were often hired because of their prowess with firearms and/or military experience.

Generally speaking, not enough has been said or written about how tough and resilient and resourceful these settlers were. Some were immigrants, some refugees from the East, and some were merely dreamers and idealists seeking a new life and place to start it. Some were outlaws, looking to prey on vulnerable people as they were encountered. Others were fleeing legal problems or even prison sentences back where they came from. Many were bigamists, thieves, murderers, or otherwise wanted felons and criminals. But most were just honest people looking for a place of their own. They weren’t stupid, and they weren’t simple, and they weren’t naive. Their raw courage and manifest strength was their mainstay, and if there’s a symbol of American heroism, they, collectively, are it. Although denigrated by ranchers and others as “clodhoppers,” “nesters,” “plowboys,” “grangers,” and other less polite nomenclature, they were basically just average people doing an most above-average thing. Most people today would pale at the prospect of even a fraction of the life-threatening difficulties they encountered and dealt with daily.

If one considers packing everything one owns into the back of what was effectively a 12x6′ U-Haul, including bedding and a place for the family, often with multiple children, to ride or sleep, then taking off for a six-to-eight month trip with nothing you couldn’t carry with you to rely on, no stores to replenish supplies from, and no real security other than what you could manage on your own, it would give an idea of what they faced. Most had no experience with the frontier, with its hazards and accidents, with the limitations of isolation and vulnerability to the elements and evils associated with a lawless and seemingly limitless emptiness that was the West. There were no roads, no convenience stops, no alternatives but to keep moving. Worries about water, food, illness or injury to both humans and animals, unscrupulous wagon-masters or fellow pioneers, combined with their defenses against everything from theft to rape to outright murder were a daily concern. Most of the other necessities of life were a daily concern, as well, including their clothing and footwear, harnesses and other tack, wagon-durability and repair, were also an hourly concern and constant irritation.

It’s one of the most fascinating and astonishing chapters of American history. There’s not a lot of romance in it. But there are some valuable lessons in the depth and strength of the human spirit.

No comments:

Post a Comment