The Double Murder Case That Still Haunts Me

The New Yorker

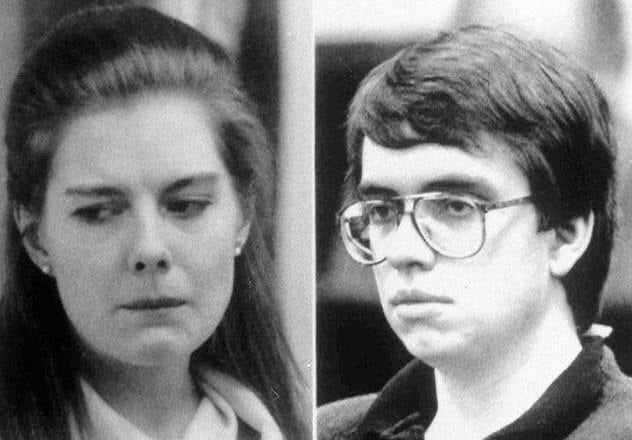

Little I have written for the magazine over the past few years has subsequently haunted me as much as a story I published, in 2015, about a thirty-year-old double murder—although, to be honest, I found it pretty haunting from the start. In the summer of 1985, two sophomores on merit scholarships at the University of Virginia—one a punctilious young German named Jens Soering and the other an aspiring bohemian named Elizabeth Haysom—left the campus and, by plane, automobile, and bus, travelled the globe. They were in love, but it wasn’t a vacation.

That spring, Haysom’s parents had been grotesquely stabbed and slashed to death at their home in the woods around Lynchburg, Virginia. The two lovers’ flight had come amid efforts by investigators to question and fingerprint Soering. The following spring, they were apprehended in London while running an elaborate check-fraud scheme. In British custody, Soering confessed to the murders. By the time that he and Haysom were returned to the United States, though, their relationship was over, and his story changed. Haysom was sentenced as an accessory before the fact, and, in June, 1990, Soering—having recanted his confession, saying that Haysom was the true killer and that he had been trying to protect her—was found guilty of the murders. Both are still in prison. A German-American documentary look at the case, “Killing for Love,” comes to New York and Los Angeles today, and will screen in other cities and towns over the next weeks.

What haunted me about the Haysom case at first was the same thing that haunted me through months of reporting. To a degree unusual in the case of a criminal conviction, every surface seemed iridescent, subject to at least two possible readings. All the people I encountered agreed that the young Soering was brilliant. But was he, as he later claimed, brilliant in the callow way of youth: cocky, borne by romantic notions, and self-sabotaging—a rising fachidiotlost in a world of wiles? Or was he, as certain data points could also suggest, brilliant in a more sophisticated way: detached, calculating, and manipulative?

Was Haysom, as she claimed, a scattered, messed-up, dreamy young woman? Or was she scattered like a fox, tossing up dust and loose ends in a consistent, even shrewd, effort to assume blame as an accessory instead of as a murderer? Both Haysom and Soering were writers in college, and both have become successful authors who have published from prison. That haunted me, too—partly because there’s an inherent slipperiness involved in interviewing people who know how stories are composed, and partly because the coverup itself seemed to have literary attributes. As I put it in the magazine piece: “At least one of the people implicated has been hiding the truth with a writer’s mind.”

The Haysom case has never left public awareness, largely due to Soering’s efforts to declare his innocence and work toward release. (He is serving a double life sentence.) But attention has been somewhat heightened this fall, for reasons due to a small convergence. Earlier this year, Soering’s primary publisher, Lantern Books, brought out Soering’s sixth book in English, “A Far, Far Better Thing,” with a brief foreword by Martin Sheen. (Sheen came into contact with Soering’s writing on Catholic theology and the iniquities of the prison system.) Its main text is a hybrid of an account that Soering first published, in German, in 2012, and a multi-chapter addendum that Bill Sizemore, a former Virginian-Pilot reporter, added as a more recent exploration of evidence and arguments. Sizemore’s tour of the case shadows Soering’s own and, both men believe, points to a wrongful conviction. “From the moment I met Soering in 2006,” Sizemore writes, “my brain rebelled at the notion that he was a monstrous killer.”

In my magazine story, I quoted Karin Steinberger, a Süddeutsche Zeitung journalist, and Marcus Vetter, a filmmaker, who were then collaborating on the documentary “Killing for Love.” It’s a marvellous narration of the case, combining current-day interviews with some footage, photos, and documents from the eighties and from Soering’s 1990 trial. Smartly structured and crisply paced, it manages to elaborate on many of the case’s peculiarities while following some of the twists and new investigative paths that thirty years of scrutiny have brought. The documentary, called “The Promise” during a festival run, is a plea, but not a polemic, for reassessment of Soering’s incarceration.

It is also a narrative with a different outline from my New Yorker piece, in part because the filmmakers did not get Elizabeth Haysom to speak on camera from prison. (Not for want of trying: there were, among other things, logistical complications.) The launch point and landing platform for their story, as with most stories today, is thus Soering; the solar system through which they guide viewers is his. After Haysom and some people from her orbit decided to speak to me, I found myself with a different reportorial mandate. The effort to bring the two systems together for the first time since the trials—to cross-check accounts and see where they deviated and converged—was a strange and turbulent undertaking. Soering and Haysom disagreed, with confidence and conviction, about even small, essentially random details that had no bearing on the murders. Each accused the other, not always without reason, of trying to commandeer and guide the public’s approach to the case. In time, I came to think this narrative enmity was as much a part of the story as the larger question of who had taken the victims’ lives. As a late arrival to their shared history—and, more still, as a writer—that haunted me, too.

Certain things, however, were clear. As I put it in the piece at the time, “The crimes of which Haysom and Soering were convicted, it has become increasingly probable, weren’t the murders that occurred.” The convicting theory of the case didn’t account for the evidence, and an additional trickle of detail since then has carried it further afield. Last year, Soering’s lawyer commissioned a closer look at DNA tests conducted in 2009. (DNA testing was not widely available in 1985, when the murder was committed.) Much of the prosecution’s physical case had rested on some spots of Type O blood found at the scene of the crime, because Soering had O blood as well. But three DNA experts taken on by Soering’s team used two samples cited in the DNA report to determine that the O-blood sample was male and yet a non-match for Soering’s DNA.

Soering and his team have taken this as unambiguously exculpatory information. “The profiles were sufficient to eliminate Jens,” his lawyer, Steven D. Rosenfield, says; they believe that, in the absence of the O-blood connection, there is no physical case against Soering. In addition to a pending parole application—Soering’s thirteenth—they have appealed to Virginia’s governor, Terry McAuliffe, for a pardon. A so-called absolute pardon would rest on the idea of innocence; a conditional pardon could rise from the idea that there would have been no conviction from the evidence as it currently stands. The pardon application has been pending for more than a year, awaiting investigation, but it is not the first effort to get Soering out of U.S. prison. Most recently, a years-long repatriation effort sought to reintegrate him into German society, via its prison system. (That effort made sense to me then, for reasons I’ve elaborated.)

This year, to help the pardon petition, Rosenfield has been enlisting law-enforcement voices for support. During my magazine reporting, when I spoke with Chuck Reid, a detective who began (but did not finish) work on the Haysom case, he expressed ambivalence about the convictions. This autumn, he wrote to the governor from a stronger position, saying that he believed Soering to be innocent. Earlier in the year, a Virginia county sheriff, Chip Harding, had also delivered an analysis with the same conclusion. (It should be noted that both men became involved through the initiative and the coöperation of Soering’s associates, who maintain an impressive catalogue of documents and living sources and helpfully mete them out to anyone on the scent. Soering, who likes to anticipate everything, tended to grow distraught when my reporting carried me into less known territory. Both of the letters by Reid and Rosenfeld draw on Soering’s approved library of information, and hew to its broad contours.) From Harding’s reading of the data, especially an unattributed spot of Type AB blood indicated as male, he offered his own theory: that two unknown men were present at the time of the murders, along with Haysom. “In my opinion, Jens Soering would not be convicted if the case were tried today,” Harding wrote.

The two-man-one-woman theory certainly fits the evidence better than the convicting narrative. But there are nagging puzzles that it does not resolve—a feature common to all theories of this haunting case—and others that it raises. (It requires one to accept that not one but three crazed murderers, two unidentified and at large, have kept their secret intact, none flinching or betraying the others, for three decades, on a heavily publicized case.) But Harding’s conclusion that Soering would not have been convicted given current evidence is significant, regardless of the question of innocence. It makes a pardon investigation seem a reasonable step. This week, Rosenfield told me, “We are optimistic.”

It is less clear when such optimism might hope to be rewarded. McAuliffe, in a gubernatorial exit interview this week, which explored his Presidential prospects (“I never take anything off the table”), noted that he was punting the Soering-pardon matter to his successor, Governor-elect Ralph Northam, who takes office on January 13th. Yesterday morning, Soering phoned me, from prison, full of resentment for the news.

“I’m devastated. I’m depressed and disappointment and angry,” he said. The petition was submitted in August, 2016, he went on, and he didn’t understand why the review was taking so long. “I’d really hoped that I would make it home for Christmas in Germany this year,” he said. He pointed to a recent decisionby the governor of California, Jerry Brown, to pardon a man named Craig Richard Coley, who had been convicted of a double murder, in 1978. “The only difference I can tell between the two cases,” Soering said, his voice now carrying the hint of a beefy Virginia twang, “is that Governor Brown is not running for President.” Governor-elect Northam, he said, was “a good man,” but it would be months before he had time to take up the issue. “Of course, people can say, what does it matter? I’ve already spent”—he paused—“thirty-one years, seven months, and fourteen days in prison. It matters to me. It matters to the people who care about me. It should matter to the justice system of Virginia.”

Soering is fifty-one now. He has not lived in the world since his teens. He told me that the rhythm of his time is much as it was when I reported my magazine piece, in 2015. “I really enjoy working out and running, so I start my day with that, and then most of the day I’m working on the case.” Due to his circumstances, even that straightforward work had extra challenges. “It’s often hard to get on the phone,” he said. “There are six phones and sixty-four guys, sixty-four guys and one e-mail kiosk. Getting on the e-mail kiosk is, like, an issue.”

I asked him about his reaction to the Steinberger and Vetter documentary. He saw it once, a year and a half ago, and said that what he’d noticed most was himself. “I guess my overwhelming reaction was just embarrassment—for what an idiot I was back then,” Soering told me.

The Double Murder Case That Still Haunts Me

No comments:

Post a Comment