How Music Helps Us Grieve

Scientists now believe that language and music co-evolved to simulate the most abiding truths of nature. Indeed, for as long as we’ve been able to articulate the human experience, we’ve made music about the most inarticulable parts of it and then used language to extol music’s power — nowhere more beautifully than in Aldous Huxley’s 1931 meditation on how music stirs the soul, in which he asserted that music’s greatest potency lies in expressing the inexpressible.

This, perhaps, is why music is so sublime a solace when it comes to the most inexpressible of human emotions: grief.

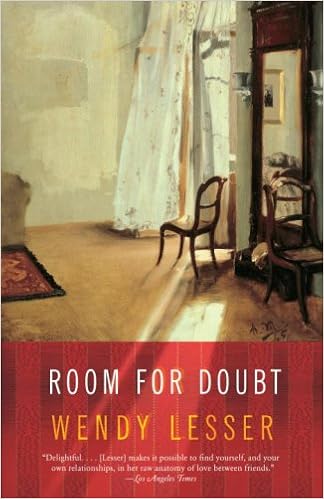

Wendy Lesser articulates this peculiar power of music in a passage from Room for Doubt (public library) — a miraculously beautiful book I discovered through Oliver Sacks’s reading list.

Lesser, who doesn’t consider herself “a particularly musical person,” contemplates the way in which music bypasses the intellect and speaks straight to the unguarded heart:

The springs of our reaction to music lie deeper than thought… Part of what music allows me is the freedom to drift off into a reverie of my own, stimulated but not constrained by the inventions of the composer. And part of what I love about music is the way it relaxes the usual need to understand. Sometimes the pleasure of an artwork comes from notknowing, not understanding, not recognizing.

Nothing befuddles our elemental need for understanding more effectively than death, the great unknown and ultimate unknowable. Music, Lesser suggests, offers a gateway not to understanding death in an intellectual way but to befriending its mystery in that Rilkean sense — something she realized in a surprising encounter with music shortly after her dear friend Leonard’s death, which she hadn’t let herself mourn.

Lesser, who had traveled to Germany for research on a book about David Hume but had somehow found herself at the auditory oasis of the Berlin philharmonic, recounts:

I had been carrying around Lenny’s death in a locked package up till then, a locked, frozen package that I couldn’t get at but couldn’t throw away, either. As long as I was afraid to look inside the package, it maintained its terrifying hold over me: it frightened and depressed me, or would have done, if I had allowed myself to have even those feelings instead of their shadowy half-versions. It wasn’t just Lenny that had been frozen; I had, too. But as I sat in the Berlin Philharmonic hall and listened to the choral voices singing their incomprehensible words, something warmed and softened in me. I became, for the first time in months, able to feel strongly again.

Revisiting the question of not understanding, or what Thoreau celebrated as the transcendent humility of not-knowing, she adds:

Later, when I looked at the words in the program, I saw that the choral voices had been singing about the triumph of God over death. This is what I mean about the importance of not understanding. If I had known this at the time, I might have stiffened my atheist spine and resisted. But instead of taking in what the German words meant, I just allowed them to echo through my body: I feltthem, quite literally, instead of understanding them. And the reverie I fell into as I listened to Brahms’s music was not about God triumphing over death, but about music and death grappling with each other. Death was chasing me, and I was fleeing from it, and it was pounding toward me; it was pounding in the music, but the music was also what was helping me to flee. And, as in a myth or a fairy tale, I sensed that what would enable me to escape — not forever, because all such escapes are temporary, but to escape just this once — would be if I looked death, Lenny’s death, in the face: if I turned back and looked at it as clearly and sustainedly as I could bear.

Complement this particular portion of the wholly magnificent Room for Doubt with beloved writers’reflections on the power of music, these unusual children’s books about making sense of loss, and psychologist Irvin D. Yalom on the role of not-knowing in our search for meaning.

No comments:

Post a Comment