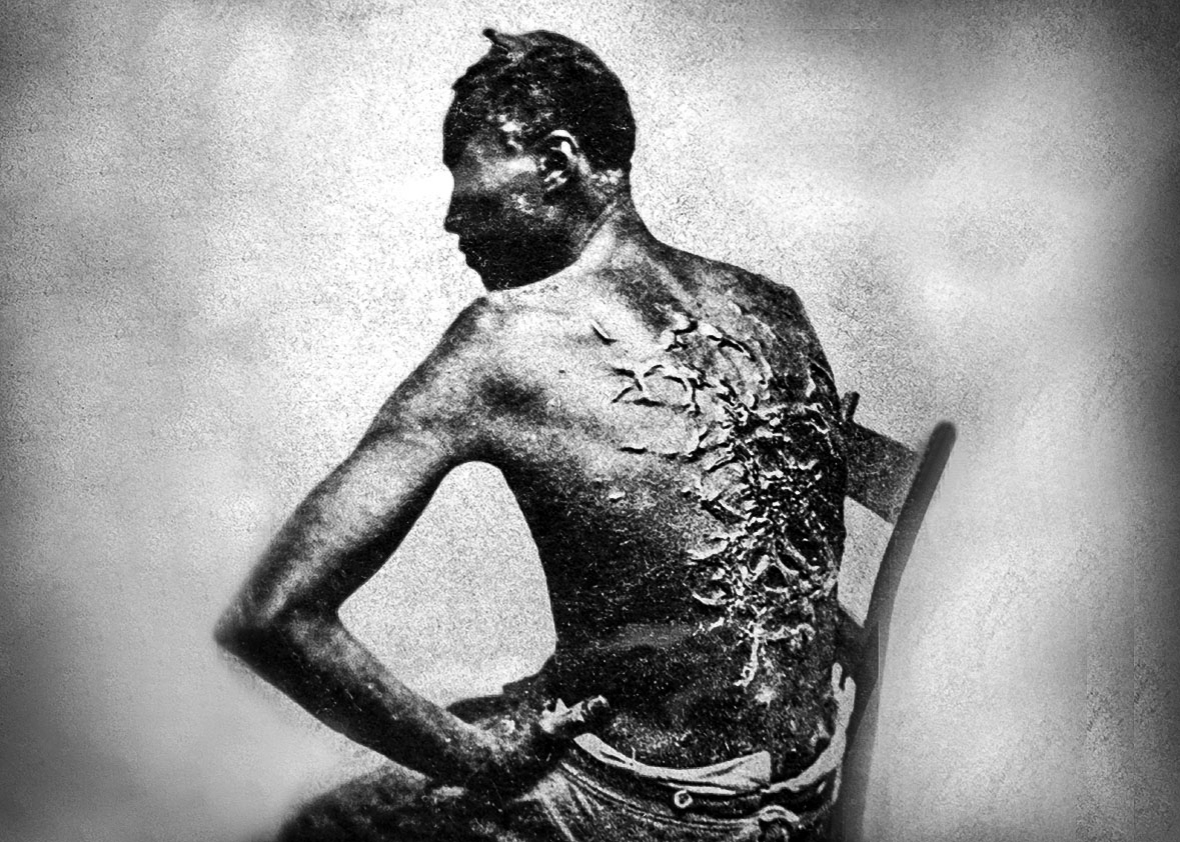

A slave named Peter, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, April 2, 1863

Alan: Southerners have been too eager to absolve themselves of centuries of slavery.

In the context of traditional Christian absolution, most southerners have neither confessed their sin nor performed penance.

Slavery Myths Debunked

By Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion

The Irish were slaves too; slaves had it better than Northern factory workers; black people fought for the Confederacy; and other lies, half-truths, and irrelevancies.

Acertain resistance to discussion about the toll of American slavery isn’t confined to the least savory corners of the Internet. Last year, in an unsigned (and now withdrawn) review of historian Ed Baptist’s book The Half Has Never Been Told, the Economist took issue with Baptist’s “overstated” treatment of the topic, arguing that the increase in the country’s economic output in the 19th century shouldn’t be chalked up to black workers’ innovations in the cotton field but rather to masters treating their slaves well out of economic self-interest—a bit of seemingly rational counterargument that ignores the moral force of Baptist’s narrative, while making space for the fantasy of kindly slavery. In a June column on the legacy of Robert E. Lee that was otherwise largely critical of the Confederate general, New York Times op-ed columnist David Brooks wrote that, though Lee owned slaves, he didn’t like owning slaves—a biographical detail whose inclusion seemed to imply that Lee’s ambivalence somehow made his slaveholding less objectionable. And in an August obituary of civil rights leader Julian Bond, the Times called his great-grandmother Jane Bond “the slave mistress of a Kentucky farmer”—a term that accords far too much agency to Bond’s ancestor and too little blame to the “farmer” who enslaved her.

While working on our Slate Academy podcast, The History of American Slavery, we encountered many types of slavery denial—frequently disguised as historical correctives and advanced by those who want to change (or end) conversation about the deep impact of slavery on American history. We’d like to offer counterarguments—some historical, some ethical—to the most common misdirections that surface in conversations about slavery.

“The Irish Were Slaves Too”

Is it true?: If we’re talking about slavery as it was practiced on Africans in the United States—that is, hereditary chattel slavery—then the answer is a clear no. As historian and public librarian Liam Hogan writes in a paper titled “The Myth of ‘Irish Slaves’ in the Colonies,” “Persons from Ireland have been held in various forms of human bondage throughout history, but they have never been chattel slaves in the West Indies.” Nor is there any evidence of Irish chattel slavery in the North American colonies. There were a large number of Irish indentured servants, and there were cases in which Irish men and women were sentenced to indentured servitude in the “new world” and forcibly shipped across the Atlantic. But even involuntary laborers had more autonomy than enslaved Africans, and the large majority of Irish indentured servants came here voluntarily.

Which raises a question: Where did the myth of Irish slavery come from? A few places. The term “white slaves” emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries, first as a derogatory term for Irish laborers—equating their social position to that of slaves—later as political rhetoric in Ireland itself, and later still as Southern pro-slavery propaganda against an industrialized North. More recently, Hogan notes, several sources have conflated indentured servitude with chattel slavery in order to argue for a particular Irish disadvantage in the Americas, when compared to other white immigrant groups. Hogan cites several writers—Sean O’Callaghan in To Hell or Barbados and Don Jordan and Michael Walsh in White Cargo: The Forgotten History of Britain’s White Slaves in America—who exaggerate poor treatment of Irish indentured servants and intentionally conflate their status with African slaves. Neither of the authors “bother to inform the reader, in a coherent manner, what the differences are between chattel slavery and indentured servitude or forced labor,” writes Hogan.

This is an important point. Indentured servitude was difficult, deadly work, and many indentured servants died before their terms were over. But indentured servitude was temporary, with a beginning and an end. Those who survived their terms received their freedom. Servants could even petition for early release due to mistreatment, and colonial lawmakers established different, often lesser, punishments for disobedient servants compared to disobedient slaves. Above all, indentured servitude wasn’t hereditary. The children of servants were free; the children of slaves were property. To elide this is to diminish the realities of chattel slavery, which—perhaps—is one reason the most vocal purveyors of the myth are neo-Confederate and white supremacist groups.

Bottom line: Even if many Irish immigrants faced discrimination and hard lives on these shores, it doesn’t change the fact that American slavery—hereditary and race-based—was a massive institution that shaped and defined the political economy of colonial America, and later, the United States. Nor does it change the fact that this institution left a profound legacy for the descendants of enslaved Africans, who even after emancipation were subject to almost a century of violence, disenfranchisement, and pervasive oppression, with social, economic, and cultural effects that persist to the present.

“Black people enslaved each other in Africa, and black people worked with slave traders, so …”

In a piece published in Vice magazine in 2005 (and still available on the Vicewebsite), comedian Jim Goad offers a series of “feel better about your history, white kids” arguments. One of his salvos: “Slavery was common throughout Africa, with entire tribes becoming enslaved after losing battles. Tribal chieftains often sold their defeated foes to white slave-traders.”

Is it true?: This is certainly true. But, as historian Marcus Rediker writes, the “ancient and widely accepted institution” of enslavement in Africa was exacerbated by the European presence. Yes, European slave traders entered “preexisting circuits of exchange” when they arrived in the 16th century. But European demand changed the shape of this market, strengthening enslavers and ensuring that more and more people would be carried away. “[European] slave-ship captains wanted to deal with ruling groups and strong leaders, people who could command labor resources and deliver the ‘goods,’ ” Rediker writes, and European money and technology further empowered those who were already dominant, encouraging them to enslave greater numbers. Both the social structures and infrastructure that enabled African systems of enslavement were strengthened by the transatlantic slave trade.

Bottom line: Why should this matter? This is a classic “two wrongs make a right” ethical proposition. Even if Africans (or Arabs, or Jews) colluded in the slave trade, should white Americans be entitled to do whatever they pleased with the people who were unlucky enough to fall victim?

Image via mythdebunk.com

“The first slave owner in America was black.”

Is it true?: It depends on how you parse the timeline. Anthony Johnson, the black ex–indentured servant whose bio opened the first episode of our podcast, did sue to hold John Casor for life in 1653, and the resulting civil court decision remanding Casor to Johnson’s ownership was (as historian R. Halliburton Jr. writes) “one of the first known legal sanctions of slavery” in the colonies. That phrase—“one of”—is crucial. The ship Desire brought a cargo of Africans from Barbados to Boston in 1634; these people were sold as slaves. In 1640 John Punch, a runaway servant of African descent, was sentenced to lifelong slavery in Virginia, while the two European-born companions who fled with him had their indentures extended. In 1641, the passage of the Body of Liberties provided legal sanction for the slave trade in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. (N.B.: The image in the meme above isn’t of Anthony Johnson. There were no photographers in 17th-century Virginia.)

Whether or not Anthony Johnson was the first American slaveholder, he was certainly not the last black person to own slaves. “It is a very sad aspect of African-American history that slavery sometimes could be a colorblind affair,” writes Henry Louis Gates Jr. on the Root, in a fascinating piece about the history of black slaveholders in the United States. Some black slaveholders bought family members, though this humanitarian arrangement doesn’t account for all of the history of black slaveholding, as Gates points out.

Bottom line: Even if Anthony Johnson was the first person in the North American colonies to hold a slave—even if many black people across the years held slaves—that doesn’t erase the fact that it was the racially based system of hereditary slavery that harmed the vast majority of black people living within it. The fact that some members of an oppressed class participate in oppression doesn’t excuse that oppression.

“Slaves were better off than some poor people working in Northern or English factories. At least they were given food and a place to stay.”

Is it true?: It was undeniably hard to be a factory worker in the 19th century. White adults (and children) labored in dangerous environments and were often hungry. But slaves were hardly in a better position.

While it makes some intuitive sense that a person would be rationally motivated to take care of his or her “property,” as the Economist’s reviewer suggested, historians have found that American slaveholders were apt to provide minimum levels of food and shelter for enslaved people. They considered black people’s palates to be less refined than white people’s, and this justified serving a monotonous diet of pork and cornmeal. Enslaved workers were expected to supplement their diets when they could, by tending their own vegetable gardens and hunting or trapping—more work to be added to their already heavy loads. Evidence shows that many enslaved people suffered from diseases associated with malnutrition, including pellagra, rickets, scurvy, and anemia.

Even if an enslaved person in the United States landed in a relatively “good” position—owned by a slaveholder who was inclined to feed workers well and be lenient in punishment—he was always subject to sale, which could happen because of death, debt, arguments in the family, or whim. Since very few laws regulated slaveholders’ treatment of enslaved people, there would be no guarantee that the next place the enslaved person landed would be equally comfortable—and the enslaved had limited opportunity, short of running away or resisting, to control the situation.

Bottom line: This is another case of the “two wrongs” fallacy. We could compare levels of mistreatment of Northern factory workers and Southern enslaved laborers and find that each group lived with hunger and injury; both findings are dismaying. But this is a distraction from the real issue: Slavery, as a system, legalized and codified the slaveholder’s control over the enslaved person’s body.

“Only a small percentage of Southerners owned slaves.”

“The vast majority of soldiers in the Confederate Army were simple men of meager income,” rather than wealthy slaveholders, writes the anonymous author of a widely-circulated Confederate History “fact sheet.”

Is it true?: According to the 1860 census, taken just before the Civil War, more than 32 percent of white families in the soon-to-be Confederate states owned slaves. Of course, this is an average, and different states had different levels of slaveholding. In Arkansas, just 20 percent of families owned slaves; in South Carolina, it was 46 percent; in Mississippi, it was 49 percent.

By most measures, this isn’t “small”—it’s roughly the same percentage of Americans who, today, hold a college degree. The large majority of slaveholding families were small farmers and not the major planters who dominate our image of “slavery.”

Typically, this fact is used to suggest that the Civil War was not about slavery. If so few Southerners owned slaves, goes the argument, then the war had to be about something else (namely, the sanctity of states’ rights). But, as historian Ira Berlinwrites, the slave South was a slave society, not just a society with slaves. Slavery was at the foundation of economic and social relations, and slave-ownership was aspirational—a symbol of wealth and prosperity. Whites who couldn’t afford slaves wanted them in the same way that, today, most Americans want to own a home.

Bottom line: Slavery was the basis of white supremacy, which united all whites in a racist hierarchy. “[T]he existing relation between the two races in the South,” arguedSouth Carolina Sen. John C. Calhoun in 1837, “forms the most solid and durable foundation on which to rear free and stable political institutions.” Many whites couldn’t imagine Southern society without slavery. And when it was threatened, those whites—whether they owned slaves or not—took up arms to defend their “way of life.”

“The North benefited from slavery, too.”

Is it true?: There’s no question that this is true. As historians Ed Baptist and Sven Beckert show in their respective books, American slavery was an economic engine for the global economy. The South’s production of cotton drove industrialization and fueled a massive commodities market that transformed the world. Naturally, this meant that slavery was vital to Northern financial and industrial interests. It’s no coincidence, for instance, that New York City was among the most pro-Southern cities in the North during the Civil War; slavery was key to its economic success. In any honest conversation about American slavery, we have to look at the tight economic links between North and South and the degree to which the entire country was complicit in the enterprise.

Bottom line: Often, this line comes from Southern defenders, who want to emphasize Northern complicity. But the two types of historical guilt aren’t mutually exclusive. It’s true that the North played a major role in sustaining the slave economy. It’s also true that slavery was based in the American South; that it formed the basis of Southern society; that white Southerners were its most fervent defenders; and that those Southerners would eventually fight a war to preserve and expand the institution.

“Black people fought for the Confederacy.”

“Historical fact shows there were Black Confederate soldiers. These brave men fought in the trenches beside their White brothers, all under the Confederate Battle Flag,” reads a statement from the South Carolina chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Is it true?: Here is a case where rhetorical precision is key. Did blacks serve in the Confederacy? Absolutely: As enslaved people, countless black Americans cooked, cleaned, and worked for Confederate regiments and their officers. But they didn’t fight; there’s no evidence that black Americans—enslaved or free—fought Union soldiers under Confederate banners.

Toward the end of the war, a desperate Confederate Congress allowed its army to enlist enslaved Africans who had been freed by their masters. A small number of black soldiers were trained, but there’s no evidence they saw action. And even this measure was divisive: Opponents attacked it as a betrayal of the Confederacy’s aim and purpose. “You cannot make soldiers of slaves, or slaves of soldiers,” declaredHowell Cobb, president of the Provisional Confederate State Congress that drafted the Confederate States of America constitution. “The day you make a soldier of them is the beginning of the end of the Revolution. And if slaves seem good soldiers, then our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”

The myth is a product of the post-war period, when former Confederate leaders worked to retroactively redefine secession from a movement to preserve slavery to a fight for abstract “state’s rights” and a hazy “Southern way of life.”

Bottom line: Even if there were black soldiers in the Confederate army, it doesn’t change the truth of the Confederacy: Its goal was the protection and expansion of slavery. The institution was protected in the Confederate constitution. “Our new government is founded upon … the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition,” said Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens in his “Cornerstone Speech.” “This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

No comments:

Post a Comment