Lately, while browsing my otherwise innocuous Facebook wall, I have seen a multitude of people sharing

a nifty, colorful flow-chart which sarcastically shows how silly it is to oppose gay marriage because the Bible prohibits it. For some reason, despite generally staying out of debates in public or online about homosexuality and the Catholic view on it, this particular chart has just really rattled me. And not because it makes a good point and suddenly throws my whole idea of Catholicism or Christianity into a crisis. In fact, it’s because it’s so poorly argued, so weakly researched, and so methodologically flawed, that I simply could not, and cannot, stand to see its errors spread.

At heart in the post is the basic issue of how one reads the text of the Bible. In other words, what type of hermeneutic do we use? This, incidentally, is in my mind the strongest reason why the Catholic approach to Scripture makes the most sense. A Catholic approach to Scripture realizes and emphatically demands that we cannot merely read the text at its most basic, surface level. In fact, to really understand the text of the Bible (or any text, especially ancient ones), we need to do much more work!

Now, the general idea of the article/flowchart I’ve seen floating around rests in the tired old argument that Christians have a penchant for making flippant, hypocritical decisions about which verses from the Old Testament are of lasting importance for the contemporary Church. The idea, which seems to be part of our dominant cultural heritage, is that the Old Testament bans a number of odd practices such as eating pork, and also explicitly condones many other seemingly abhorrent behaviors like mass murder, males being allowed to divorce while females weren’t allowed to, etc. The assumed solution to this difficulty is to declare that there’s no logical way to distinguish between which laws still apply and which don’t, and therefore that if one doesn’t take Scripture wholesale in a literal fashion (in the contemporary sense of the word, not the way this word is used in scholarship), then one can’t really claim to be Christian, or Bible-believing.

This is not a problem that has gone unnoticed in Christian circles. That may come as a surprise for the author of the flowchart. In point of fact, the New Testament highlights the importance of correcting some of the laws of the OT toward the purpose they were originally meant to serve, as well as dispensing with some of those laws which were of a concessionary nature.

For instance, the Pharisees question Jesus about the utility of divorce, and whether it is allowed. As the scholars of the law, they were no doubt aware that Moses and the Deuteronomic code allowed for, and gave specific instructions about divorce. But Jesus’ rejoinder to them is that God never meant for divorce to be allowed. His design, from the beginning, was that the marital union of man and woman would be forever, permanent. Divorce, Jesus says, was allowed due to the hardness of the Israelite’s hearts. It is worth briefly noting here that the prevalence of divorce in Christian circles is indeed a stumbling block to the new evangelization, especially in those Christian communities which have, as it were, in their own way drawn up a legitimate way of making use of divorce.

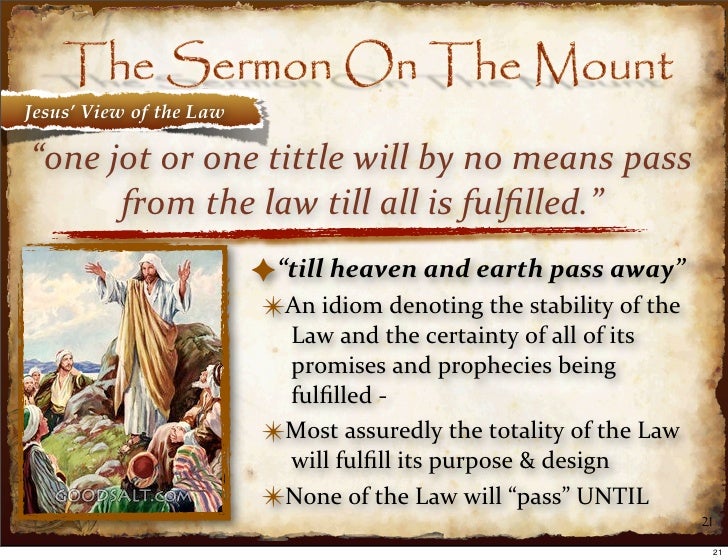

This is a prime example of the fact that even during Jesus’ own life, the question of which passages, which laws, which verses had enduring value, and which perhaps were no longer necessary. In fact, at the heart of Jesus’ most significant sermon, the Sermon on the Mount, the Lord Himself takes up a number of such issues (adultery, anger, retaliation, etc.).

But perhaps fewer are aware that even in the Old Testament, the same question, that of which laws would be enduring and which were temporary concessions, is already addressed. This issue is most clearly laid out in Ezekiel, Ch. 20:

Moreover I gave them statutes that were not good and ordinances by which they could not have life (Ez. 20:25)

This declaration is incredibly important. It is an acknowledgement that some of the OT laws were not good; they were, in fact, bad, especially with the hindsight of history. There’s a very natural way of understanding this rationale, too. Parents are frequently searching for more and more specific rules, more clear prohibitions and at times even outright concessions to try and help get the point across or to survive a crisis (like giving a child a piece of candy so that they’ll stop having an insane fit in the middle of somebody’s eulogy). In a similar fashion, in the relationship between God and Israel, the same principle is at work.

God reveals himself as a Divine Father, and Israel is His firstborn. In the course of Israel’s childhood, they rebel, break rules, and in so doing, necessitate more and more rules (hence the multiplication of laws from the original command to Adam and Eve, to the decalogue, to finally the extremely long Levitical and Deuteronomical codes). As their rebellion continues, the rules become stricter, and in some circumstances, objectionable, but they are necessary to get Israel back on track, or to prevent further wandering.

What is particularly fascinating about this situation is that even Ezekiel is not the first instance of highlighting the difficulty of some of the OT laws which were of a concessionary nature. There is, in fact, a significant scholarly tradition examining the relationship between covenants and treaties in the Ancient Near East, and the structure of the various covenants found in the Old Testament. M.G. Kline, in the 1960s, examined the structure of covenants in the ANE and found that not all covenants are equal. Some covenants, like Sinai, are clearly kinship style covenants in which the parties of the agreement are on more-or-less equal terms and in which the covenant has an overt familial style. The family relationship is a key for understanding covenants. In the ancient world, a covenant was always seen as an extension of kinship from one party to another. So, at Sinai, God is clearly extending familial rights to the Israelites.

Another popular form of covenants is the vassal or treaty-style. This is an agreement between a superior party and an inferior, in which the former issues stipulations of behavior, with clearly laid-out consequences should the inferior party violate their code of behavior. The overtones of a vassal treaty focus much more on the consequences and stress the inferiority of the receiving party. And yet, while all of the negative elements are strongly emphasized, both in the verbalization of the treaty and in its ritual enactment, there is still a familial aspect. But because of the hardness of heart of Israel, i.e. their refusal to obey the commands of prior covenants, God acts more severely in Deuteronomy and includes a number of concessions to them, and an almost insistence that the curses will be enacted, as Israel had shown itself already unable to live up to the demands of previous covenants. There’s much more that could be said on the subject, but one final piece of the argument remains.

The location in which Deuteronomy was stored, and the manner in which it is delivered, gives us clues even from within Deuteronomy itself that the Israelites would have been aware that the nature of this second law (the literal meaning of Deuteronomy; deutero-second nomos-law) was already a step further from the relationship God desired to have with them initially.

Whereas the Decalogue was stored inside the Ark of the Covenant, highlighting its enduring value, the Deuteronomical code was not allowed such a proper storage location. It was placed merely alongside the Ark, rather than inside of it. In addition, note the difference between the law at Sinai, which is delivered by God Himself. In the Deuteronomical code, the legislation is all given by Moses, as a mediator. This is theologically significant. The code is coming through a mediator, rather than directly from God. A few more things happen in Deuteronomy that show it to be a lower-level, treaty-style covenant:

Laws Unique to Deuteronomy

- Central sanctuary

- Profane slaughter of unclean animals

- Regulations for the king

- Herem warfare

- Legislation for divorce and remarriage

- Usury can be collected from non-Israelites

- These are all practices “assimilated by OT laws rather than ones devised by them.” In addition, Deuteronomy’s ethnic and nationalistic bent was reinforced by its own distinctive cult rituals.”

I wish there was room to say more, but let me finish with one final thought. The original claim of the author of the flowchart was to show that the Bible prohibits many behaviors which we today find unobjectionable. Even Christians eat pork, many divorce and remarry, etc. The claim is then that if we’re going to be consistent with the Bible’s logic, we should “read all the paperwork” and know that we can’t have recourse to Scripture unless we’re prepared to take its logic wholesale, without picking and choosing.

The problem with this claim is that it ignores mountains of evidence in scholarship, and even passages WITHIN DEUTERONOMY ITSELF which show clearly that not all of the OT laws were granted the same status. Deuteronomy is quite plainly “another law” and scholars have shown it to take the shape of a vassal treaty. Ezekiel later on is clear that some of the laws in the OT were bad, and were laws which could not give life. Jesus himself takes up some of the key examples in the Gospels. And all parents know that, in the development of children, concessions sometimes simply must be made, but that they are temporary. All of this is to say that the hermeneutic suggested by the flowchart above is foolhardy and out of touch with the reality of how Scripture works, what scholars have discovered, and what the intent of the authors of the text itself.

Pax,

Luke

.

No comments:

Post a Comment