Merton's favorite song was "Got My Mojo Working"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Got_My_Mojo_Working

***

Merton Quotes

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2012/04/merton-best-imposed-as-norm-becomes.html

***

Fifty years ago this November, Thomas Merton hosted a small retreat on the spiritual roots of protest at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky. Tom Cornell and I plus Dan and Phil Berrigan were at the time in the process of launching the Catholic Peace Fellowship — the retreat was a helpful factor in framing our approach to the work we would be doing in the years that followed. Among the other participants were John Howard Yoder, A.J. Muste and W.H. Ferry.

Gordon Oyer -- see the attached letter -- has done remarkable job of discovering material about what we discussed and did during our several days together. The book that has come out of his research, “Pursuing the Spiritual Roots of Protest,” is finally in print. A number of photos I took at the time are being published for the first time.

Jim

PS Also attached is my foreword to Gordon’s book.

* * *

From: Gordon Oyer <gordonoyer@gmail.com>

Date: Sat, Mar 8, 2014 at 8:50 PM

Subject: Gordon's Book Released

Resorting to self-promotion, I'm sharing that this week the book I’ve worked on for 5 years was published:

Pursuing the Spiritual Roots of Protest

It evolved from mere curiosity to a book contract so gradually that by the time it occurred to me grant support might be available, the research was done. I’ve funded the translations, transcriptions, travel, copyright permissions, etc. myself. The project also induced personal as well as financial costs. But I’d held writing/publishing a significant historical monograph as an unlikely dream since high school. So this feels awfully good.

The topic—a 1964 retreat that addressed “spiritual roots of protest”—may seem odd for someone with my lack of public engagement. On that, I’ll just say (1) writing it created no small amount of cognitive dissonance and (2) the content seems incredibly timely and vital. In both historical and (especially) geological time, we as a society and a species are nearing the edge of a cliff at warp speed. The forces they considered oppressive and protest-worthy 50 years ago are still there, but have ballooned from Eisenhower’s “military-industrial complex” to Mike Lofgren’s “deep state” (see him explain it on Bill Moyers here: http://vimeo.com/87243281).

Those forces drive unconscious processes we all instinctively embrace, rather than any obvious or conscious “conspiracy.” They are processes to which we need awakened and which we need to resist and oppose on as many levels as we can. My hope is that this book, though a story of the past, can help stir some current reflection on how nonviolent faith commitments interface with those processes and inform our responses.

It has 300 pages total, reflects a lot of primary archival research, and includes never-before-published photos and documents (as appendices). I hope you’ll take a look. And if inclined, forward the email to anyone you think it might interest.

Gordon Oyer

* * *

Foreword

Since Christian monasticism began to flower in the deserts of Egypt, Sinai and Palestine in the fourth century AD, millions of people have gone on monastic retreats, and it still goes on. It’s not hard to find those who would welcome a few days of tranquility in a place where the core activity of one’s quiet hosts is worship and prayer.

Many people who seek monastic hospitality say they are there to experience peace. What is truly unusual is for someone, still less a group of people, to seek the shelter of a monastery in hopes of becoming better equipped to be peacemakers, but this is exactly what fourteen people did for three days in November 1964 at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky. We used our time together both to explore what we were up against and how best to respond.

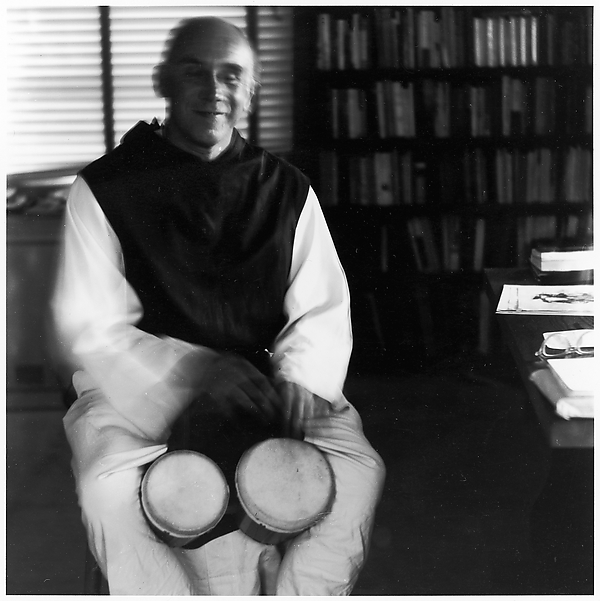

Our host was Thomas Merton, one of the most respected Christian authors of the twentieth century. At the time he had been a monk at Gethsemani for almost 23 years and was serving the community as Master of Novices. What had made him well known to the outside world was his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, a hard-to-put-down account of what led him to Christian faith, the Catholic Church and a monastic vocation. Published in 1948, it had become an international bestseller and finally a modern classic. It is often compared to Augustine’s Confessions.

Merton had been thinking about war from an early age. His birth in France (his mother from America, his father from New Zealand) coincided with the initial months of World War I, a catastrophe his anti-war father managed not to take part in. By the time World War II had begun, Merton’s recent conversion to Christianity had led him to pacifist convictions — it was obvious to him that killing was incompatible with the teaching of Jesus. While others were putting on military uniforms, Merton put on a monastic robe. By the time of the 1964 retreat, he was the best known and most widely read Christian monk in the world.

In 1961, writing for The Catholic Worker, Merton had argued that “the duty of the Christian in this [present] crisis is to strive with all his power and intelligence, with his faith, his hope in Christ, and love for God and man, to do the one task which God has imposed upon us in the world today. That task is to work for the total abolition of war.” Many essays along similar lines followed as well as a book, Peace in the Post-Christian Era, but its publication had been stopped by the head of the Trappist order in Rome, Dom Gabriel Sortais, who felt that it was inappropriate for a monk to write on such controversial topics.

By the time of the retreat, Merton had become one of the founders of the newly-launched Catholic Peace Fellowship, which just a few weeks later would open a national office in Manhattan. Besides Merton, four others taking part in the retreat were CPF co-founders: Tom Cornell, and Daniel and Philip Berrigan, and myself.

One of the striking aspects of the retreat was that not all those taking part were Catholic, a fact that is unremarkable today but was rare and controversial in 1964. The most senior retreat participant was 79-year-old A.J. Muste, a Quaker who had once been a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church; by the time of our gathering he was perhaps the most distinguished leader of the U.S. peace movement — former executive secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and now chairman of the Committee for Nonviolent Action. There was John Howard Yoder, the distinguished Mennonite scholar; eight years later he would publish The Politics of Jesus, a book still widely read. W.H. Ferry, vice president of the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, was a Unitarian at the time who, later in life, described himself simply as a Christian. Elbert Jean was a Methodist minister from Arkansas who had been deeply immersed in the civil rights movement. Another participant was John Oliver Nelson, a Yale professor who was a leader of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and founder of Kirkridge, a conference and retreat center in Pennsylvania.

My memories of the retreat begin with place and weather. Rural, rolling Kentucky was wrapped around the abbey on every side. The monastery in those days was mainly made up of weathered, ramshackle buildings, with the oldest dating back more than a hundred years. The weather was damp and chilly, the sky mainly overcast, with occasional light rain. It was due to the weather that we met mainly in a small conference room in the gatehouse that normally was used by family and guests visiting monks. There were only two sessions at Merton’s hermitage, a simple flat-roofed, one-storey structure about a mile from the monastery. It was made of gray cinder blocks. Heat was provided by a fireplace. Whether in gatehouse or hermitage, it was a squeeze fitting all fourteen of us into the available space.

Merton, wearing his black-and-white Trappist robes, served as the retreat’s central but never dominant figure. At each session, by prearrangement, one of the participants made a presentation, at the end of which there was free-wheeling discussion.

What did we talk about in those intense three days?

While many issues were aired, three major themes survived in my unaided memory: conscientious objection to war, the challenge of technology, and a provocative question Merton raised: “By what right do we protest?”

Conscientious objection: Before the Vietnam War, refusal to take part in war (Jim Forest had "conscientious objection" here in the place of my word "war" - Wendy) had been mainly linked with several small “peace churches” — Quakers, Mennonites and the Church of the Brethren — while the Catholic and large Protestant churches produced relatively few conscientious objectors. But the times were about to change with Vietnam, a country few Americans could find on the map, providing the catalyst. Several months earlier Congress had approved the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting President Lyndon Johnson unilateral power to launch a full-scale war in Southeast Asia if and when he deemed it necessary. As far more soldiers would be needed than voluntary recruitment could hope to provide, drafting hundreds of thousands of young men would prove essential.

One element of our discussion was to consider the case of Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian Catholic layman who had been executed in Berlin in 1943 for refusing to fight in what he judged to be an unjust war. What if his story and stories like it were to become better known? What if significant numbers of young American Christians were to follow Jägerstätter’s example and say no to war? (In the years that followed the retreat, the Catholic Peace Fellowship did much to promote awareness of the Jägerstätter story, its New Testament basis and its implications in our time. The CPF’s draft counseling and educational work help explain the astonishing fact that the Catholic Church in the U.S. produced the largest contingent of conscientious objectors during the Vietnam War.)

Technology: Thanks especially to W.H. Ferry, technology was a major topic for us. “Ping,” as he was known to friends, brought home to us the implications of the technological credo, “If it can be done, it must be done.” Every possibility, once envisioned and no matter how dangerous, toxic or ultimately self-destructive, tends to become a reality, nuclear weapons being only one of countless examples. The technology of destruction as it advanced war-by-war had become truly apocalyptic. The threat was fresh in all our minds — two years before the retreat, during the Cuban missile crisis, the world had been poised on the brink of nuclear war. But it wasn’t only a question of weapons of mass destruction. Increasingly our lives were being shaped and dominated by technology.

Protest: For me, Merton’s question — “By what right to we protest?” — was something of a Zen koan — an arrow in the back that one’s hands cannot reach to dislodge. Coming from a left-wing family background, it seemed so obvious to me that, when you see something wrong, you protest, period. Protest is part of being human. Merton and others at the retreat made me more aware that acts of protest are not ends in themselves but ultimately must be regarded as efforts to bring about a transformation of heart of one’s adversaries and even one’s self. The civil rights movement was a case in point; in recent years it had already brought about significant positive change in America. Thanks to its largely nonviolent character, it was an example of how to protest in ways that help change the outlook of those who are threatened by change. Merton put great stress on protest that had contemplative roots, protest motivated not only by outrage but by compassion for those who, driven by fear or a warped patriotism, experience themselves as objects of protest.

In the years that followed, I never forgot these three elements in our exchange, but there was a great deal more that slowly faded from memory. How often I wished I had brought along a tape recorder in order to listen in once again, or at least had kept better and more legible notes. Now decades later I’ve found the next best thing: the curiosity and relentless digging of Gordon Oyer. Drawing on notes made by myself and others plus letters and other writings of those who took part as well as interviews with the few of us still alive, Gordon has done an amazing job of reconstructing our conversations — as you are about to find out.

-- Jim Forest

* * *

Jim & Nancy Forest

Kanisstraat 5 / 1811 GJ Alkmaar / The Netherlands

Jim's books: www.jimandnancyforest.com/

Kanisstraat 5 / 1811 GJ Alkmaar / The Netherlands

Jim's books: www.jimandnancyforest.com/

Jim & Nancy web site: www.jimandnancyforest.com

On Pilgrimage blog: http://

In Communion site: www.incommunion.org

In Communion site: www.incommunion.org

No comments:

Post a Comment