Compiling as a Creative Act

by Maria Popova

Is genius a mosaic of “magpielike borrowings”?

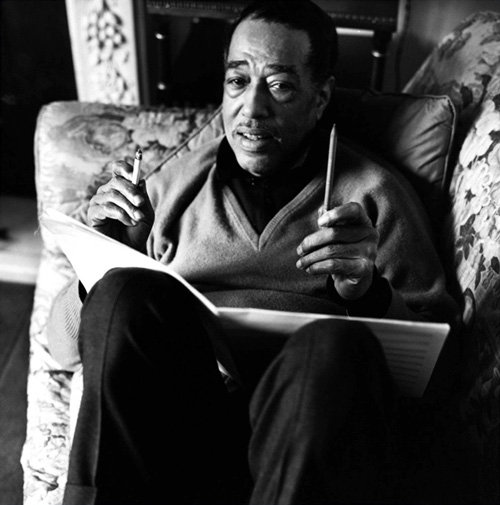

In the altogether fantastic Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington (public library) — one of the best biographies and memoirs of 2013 — Terry Teachout reveals that for the beloved composer, who was already a man of curious paradoxes, this creative duality was as palpable as the line between plagiarism and originality was blurred. Ellington, it turns out, made a regular habit of “borrowing” melodic fragments composed by the soloists in his famed orchestra, then transforming them into hit songs — without credit, creative or financial, to the originators. Teachout writes:

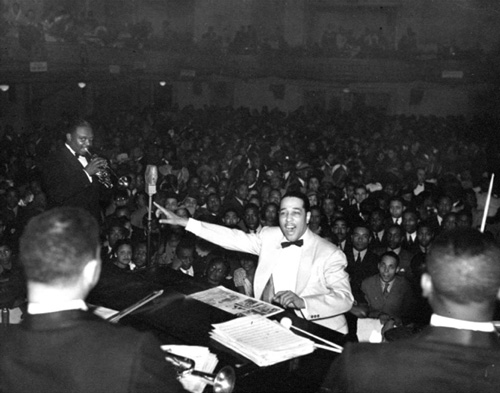

Not only was Ellington inspired by the sounds and styles of his musicians, but he plucked bits and pieces from their solos and wove them into his compositions. Some of his most popular songs were spun out of melodic fragments that he gleaned from his close listening on the bandstand each night. “He could hear a guy play something and take a pencil and scribble a little thing,” the pianist Jimmy Rowles said. “The next night there would be an arrangement of that thing the guy played. And nobody knew where it came from.” This symbiotic relationship was important to Ellington’s success as a popular songwriter, since his prodigal gifts did not include the lucrative ability to casually toss off easily hummable tunes. He had to work at it, and sometimes he needed a little help. “More than once,” Rex Stewart recalled, “a lick which started out as a rhythmic background for a solo or a response to another lick eventually became a hit record, once Duke’s fertile imagination took over and provided the proper framework.” He took it for granted that such joint creations were his sole property, but if payment was unavoidable, he tried when possible to dole out modest flat fees rather than share with his musicians the publishing rights to (and royalties from) the pieces that he based on their “licks.” It was as much a matter of vanity as money, for Ellington preferred for the public to think that he did it all by himself.

Ellington’s soloists took his “magpielike borrowings” with varying degrees of emotion. Teachout cites one, who found them almost amusing:

Oh, he’d steal like mad, no questions about it. He’d steal that from his own self.

Another observed them with matter-of-fact fascination that borders on resignation:

All of us used to sell the songs to him for $25. Some of the fellas, in later years, they sued him. But I didn’t do it. No, I believed in if I sold a person something and he paid for it, I didn’t believe in going back, you know, and saying I didn’t mean it that way. So I let it go. It was fun then. You know, I got a lot of experience doing things like that. And it was a pleasure, you know, to have the band to play your song. To have someone playing your song. That’s why we did it.

But some of Ellington’s musicians were outraged by the practice, feeling both creatively betrayed and financially cheated when Ellington transformed material he had bought from them for next to nothing into a hit song that made him a fortune. Teachout writes of the trombonist Lawrence Brown, one of Ellington’s most acclaimed soloists:

Brown saw the practice as a form of musical kleptomania and the Ellington band as a “factory” for the manufacture of collective compositions to which the leader signed his name alone. “Every man in there was a part of the music, the band, and everything that happened, and every successful move that the band made,” he said — and not just to interviewers, but to Ellington himself. “I don’t consider you a composer,” the trombonist told his boss early in their relationship. “You are a compiler.”

Indeed, this image of Ellington as a compiler was a recurring impression, but one of ambiguous interpretation — was it a creative genius that transformed forgettable bits into timeless masterpieces, or an act of betrayal and artistic vanity at the expense of integrity? Trumpeter Clark Terry, one of the stars in Ellington’s band, described Duke as “a compiler of deeds and ideas, with a great facility to make something out of what would possibly have been nothing.” But that’s not necessarily an un-creative thing — in fact, it’s rather the opposite. Teachout cites music critic Alex Ross, who writes in the indispensable The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century:

Ellington carved out his own brand of eminence, redefining composition as a collective art.

In this light, the words of music writer and historian Stanley Dance in the eulogy he delivered for Ellington ring with another layer of poignancy: Dance called him “the greatest innovator in his field, and yet paradoxically a conservative, one who built new things on the best of the old.” It was, no doubt, a compliment on the mastery with which Ellington built on the legacy of jazz, not a dig on his unabashed creative borrowing that bled into plagiarism. And therein lies another eternal human paradox that Ellington embodied: Is it possible to be both a plagiarist and an innovator? Ellington lived the answer with remarkable aplomb.

But the real question, of course, isn’t whether creativity is combinatorial and based on the assemblage of existing materials — it is. What Ellington did was simply follow the fundamental impetus of the creative spirit to combine and recombine old ideas into new ones. How he did it, however, was a failure of creative integrity. Attribution matters, however high up the genius food chain one may be.

In this excerpt from his conversation with Debbie Millman on Design Matters — the full interview is spectacular and very much worth a listen — Teachout discusses Ellington’s prolific borrowing, the conundrum about creativity it presents, how it challenges the “sole genius” myth of art, and how it resembles the process of movie-making:

Why [this] matters so much to us is precisely because Ellington is a great composer [but] our idea of what a great composer is is conditioned by classical music, in which somebody is sitting in a studio and they are writing the piece out from beginning to end and it’s not a mosaic in which they utilize other people’s materials.

Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington is itself, for some wonderful symmetry in this context of compiling as a creative act, what Teachout calls “not so much a work of scholarship as an act of synthesis.” It is also more than a biography — it’s a masterwork of insight into the convoluted psychology of a conflicted creative genius who forever changed the course of music and culture.

and culture.

and culture.

and culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment