That’s not because we don’t have to get the problem under control; it’s because I’m pretty sure we will. Why? The budget deficit is unique: If Congress is unable to agree on a remedy, the problem goes away on its own. Would that all of our challenges were so cooperative.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke calls the end of 2012 “a fiscal cliff.” The Bush tax cuts are set to expire. The $1.2 trillion spending sequester, enforcing cuts in the defense and domestic budgets, is set to go off. Various stimulus measures -- including the payroll tax cut -- are scheduled to end. “Taken together,” writesthe Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “these policies would reduce ten-year deficits by over $6.8 trillion relative to realistic current policy projections -- enough to put the debt on a sharp downward path.”

In fact, if Congress gridlocks -- and what does Congress do these days but gridlock? -- we face the prospect of too much deficit reduction too fast. TheCongressional Budget Office estimates that barreling over the fiscal cliff would increaseunemployment by 1.1 percent in 2013.

Common Goal

Inaction isn’t inevitable: Deficit reduction is an unusual issue in that both parties fundamentally agree on the goal, even if they don’t agree on how to achieve it. This past week, for instance, President Barack Obama and Representative Paul Ryan traded barbs on how best to go about it. The same can’t be said for issues such as catastrophic climate change or access to health insurance, in which the two parties disagree on whether there’s even a problem that needs federal action.

Finally, Washington is thick with potential crises -- real and invented -- that will be used to increase the urgency of deficit reduction. There are appropriations bills to pass in order to keep the federal government functioning. There’s raising the debt ceiling, which we’re expected to breach at the end of 2012. There’s the expiration of the various tax cuts and stimulus measures. And, if all this is somehow surmounted without further deficit reduction, there’s the eventual pressure the bond market will exert on the economy and policy makers. No other issue is subject to such a varied and continuous array of forcing mechanisms.

Some of those mechanisms have already proved their effectiveness. The 2010 debt-ceiling debate led to the Simpson- Bowles commission. The 2011 government-shutdown debate led to a small deficit-reduction package -- the participants estimated it at $37 billion over 10 years. The 2011 debt-ceiling debate, though a disaster for the economy, led to a deficit-reduction plan of $2.1 trillion -- about half the size of the Simpson- Bowles plan. These outcomes point the way to deficit deals that might be struck in the next year or two, with the potential to stabilize our finances for the next decade or more.

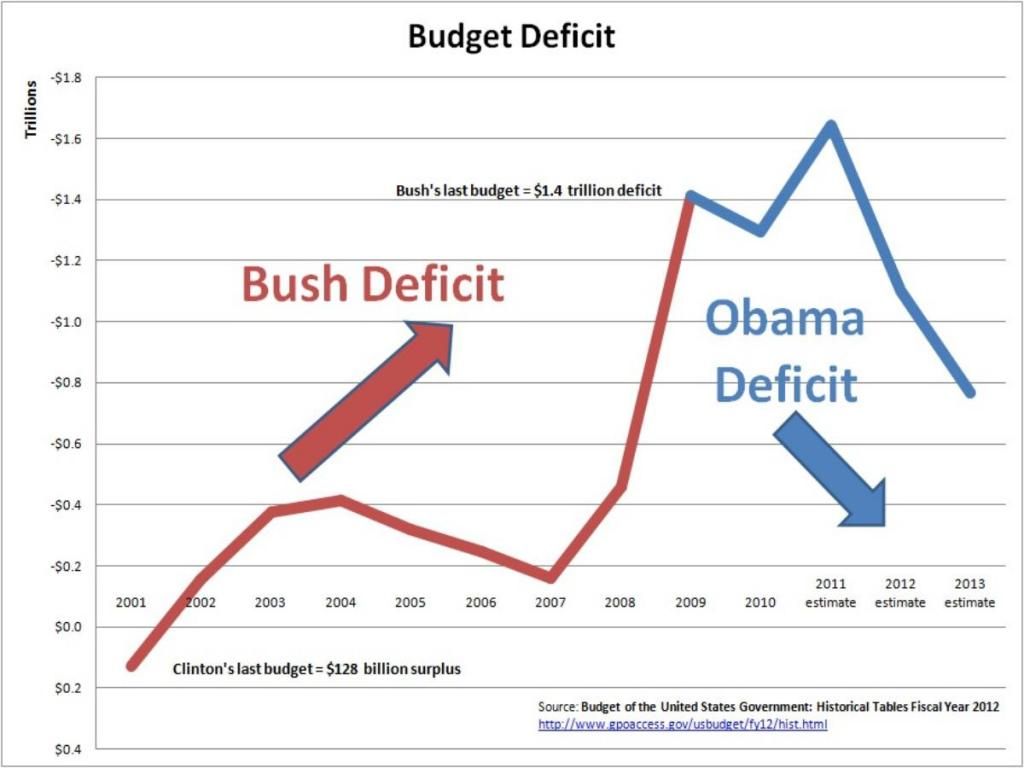

That won’t comfort some of the most ardent deficit hawks. They are, for better or worse, considerably more farsighted. They brandish charts showing scary red lines reaching out to 2080. Those charts show a huge problem that requires radical solutions. I know those charts well. I’ve used them myself. But those charts are really about health-care spending, as you can see here. What they’re really telling us is this: If you look at how medical costs have risen in recent decades and you draw that line out for 70 more years, we’re really in trouble. And that’s true: We are.

But there’s something ridiculous about extrapolating current trends all the way out to 2080. By that point, we’ll probably either be robots, the servants of robots or a bit of both. Either way, the health-care system will probably undergo dramatic change.

No Pacemakers

Look what happens when you turn back the clock 70 years from today. That puts you in 1942, the year John Bumstead and Orvan Hess first saved a patient’s life using penicillin. There were no pacemakers, oral contraceptives or chemotherapy. Water wasn’t fluoridated, and health insurance was a niche product. Imagine trying to predict the trajectory of today’s health-care system from that vantage point. How incredibly, hilariously wrong would we have been?

In part for that reason, we don’t balance the budget for 70 years at a time. Indeed, we usually don’t even balance it for 10 years at a time. Instead, we muddle through, striking deals that are smaller than wonks like, but sufficient to keep us out of the woods. That’s what we did in the 1990s, which featured deficit-reduction bills in 1991, 1993, 1995 and 1997. We’ll probably follow a similar path in the decade to come.

Of course, you can muddle wisely or muddle stupidly. I worry we’ll choose the latter. Evidence is already mounting: The sequester is a stupid way to cut spending. Letting the Bush tax cuts expire all at once is a stupid way to raise taxes. And repeatedly forcing the country to the brink of default is a stupid way to manage our budget.

Worse, too much deficit reduction too fast will hurt economic growth. You can see that happening in Europe, where an excess of austerity has tipped a number of nations into fiscal holes they can’t seem to climb out of. In a city as obsessed with deficits as Washington, yet unwilling to strike smart deals that pair long-term deficit reduction with short-term support for the economy, a bad turn in the economy or a set of policy misjudgments remain a real threat.

Nevertheless, I’m confident that we will, one way or another, muddle through. Because when it comes to the deficit, Congress really has two choices: Do something to solve it, or do nothing and let that solve it. The same can’t be said for issues such as infrastructure and loose nukes and climate change and preparing for pandemic flu. On those questions, congressional inaction isn’t enough to make the problem disappear. So those are the issues I worry about.

(Ezra Klein is a Bloomberg View columnist. The opinions expressed are his own.)

To contact the writer on this story: Ezra Klein in Washington at wonkbook@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment