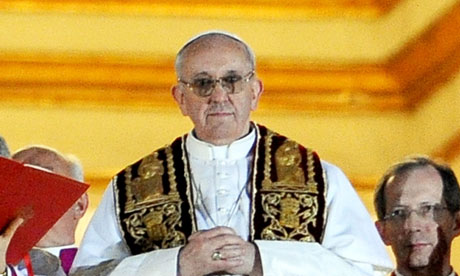

Pope Francis discusses the divine and the mundane in his book On Earth and Heaven. Photograph: Olycom SPA / Rex Features

Pope Francis's book reveals a radical progressive in the making

Book written as a cardinal shows a man with a profound social conscience and professing a genuine belief in interfaith dialogue.

In his own words, Pope Francis comes over as a clever, thoughtful and skilful mixture of social conservative and radical progressive who preaches zero tolerance of pederast priests but whose own behaviour during the terror of Argentina's military juntas remains decidedly blurred.

In his latest book, On Earth and Heaven, the man then known as Jorge Bergoglio, discusses the divine and the mundane with the prominent Jewish rabbi Abraham Skorka in a series of conversations published in 2010.

Bergoglio appears as a man with a profound social conscience, expressing admiration of some atheist socialists and professing a genuine belief in interfaith dialogue – to the extent that some radical Catholics accuse him of heresy.

He is critical of those who covered up the paedophile scandal that has done so much damage to the church he now leads.

"The idea that celibacy produces paedophiles can be forgotten," he says. "If a priest is a paedophile, he is so before he becomes a priest. But when this happens you must never look away. You cannot be in a position of power and use it to destroy the life of another person."

Bergoglio says he has never had to deal with such a case, but when a bishop asked what he should do, he told him the priest should be sacked and tried, that putting the church's reputation first was a mistake.

"I think that is the solution that was once proposed in the United States; of switching them to other parishes," he says. "That is stupid, because the priest continues to carry the problem in his backpack." The only answer to the problem, he adds, is zero tolerance.

The church, he says, has been through worse times. "There have been corrupt periods. There were very difficult periods, but the religion revived itself."

He also recognises that the church must move with the times and be in constant transformation. "If, throughout history, the church has changed so much, I do not see why we should not adapt it to the culture of the [our] time," he says.

But he sticks to Catholic dogma on key issues, writing off gay marriage as "an anthropological reverse".

Abortion is a scientific problem that is separate "from any religious concept".

"Preventing the development of a being that already has the genetic code of a human being is not ethical," he says.

Some of his harshest words are for ultra-conservatives who put obedience of church rules above everything else. "There are sectors within the religions that are so prescriptive that they forget the human side," he says.

That may explain why, according to a leaked cardinal's diary from the 2005 papal conclave, he allegedly once criticised anti-condom zealots as wanting to "stick the whole world inside a condom".

But it may also be the result of criticism he received for once joining a stadium full of protestant evangelists – seen by some Catholics as the biggest threat to their supremacy in Latin America – in their prayers.

"The following week a magazine produced the headline: 'Archbishopric of Buenos Aires, an empty chair. The archbishop has committed the crime of apostasy'," he complains.

The allegations by journalist Horacio Verbitsky, who accuses him of covering up the church's connivance with the silencing of the disappearance, torture and murder of political opponents, are dismissed with a reference to another book of interviews in which he gives his explanation.

"The horrors committed under the military governments were revealed only drip-by-drip, but for me they are still one of the worst blights on this country," says Bergoglio, suggesting that he himself only slowly became aware of the abuses.

He expresses his admiration for the atheist socialists who helped bring social justice to Argentina, but recognises that some socialists end up leaving the church. "Generally it is because they have conflicts with the church structure, with the way of life of some believers who, instead of being a bridge, become a wall."

And he warns against a globalisation that does not respect cultures. "The kind of globalisation that makes things uniform is essentially imperialist," he says, adding that cultural diversity must be conserved. "At the end it becomes a way of enslaving people."

And he reveals what he most admires about Saint Francis of Assisi, from whom he would later take his papal name.

"He brought to Christianity an idea of poverty against the luxury, pride, vanity of the civil and ecclesiastical powers of the time," he says. "He changed history."

But he refuses to separate charity from religion – and even warns the church against becoming a simple NGO.

And the man who now leads 1.2 billion Roman Catholics across the world has a clear idea of leadership. "A religious leader can be strong, and very firm, but without being aggressive," he says. "Whoever leads should be like those who serve. When he stops serving he becomes a mere manager, a representative of an NGO."

No comments:

Post a Comment