Trident: Illegal And Immoral

The Ultimate Logic Of Trident Is Omnicide

Kings Bay Plowshares

THE COURT: All right. We will now turn to Mr. O'Neill.

Mr. O'Neill, if you would please step up to the witness

stand.

THE CLERK: If you'll please raise your right hand to be

sworn.

PATRICK O'NEILL, having been affirmed to tell

the truth, testified as follows:

THE WITNESS: I affirm that.

THE CLERK: Thank you. You may be seated. Please state

your full name and spell your last name for the record.

THE WITNESS: Patrick O'Neill.

O apostrophe capital N-E-I-L-L.

So I'm -- I was -- I was told that I shouldn't

cross-examine anybody today, so I was very faithful staying in

my seat and not doing that.

THE COURT: Mr. O'Neill, one question before you get

started. Understanding that you're proceeding pro se here, you also have standby counsel in this case as well.

THE WITNESS: Yes. My standby counsel is Darrell

Gossett right there.

THE COURT: Yes. And you've seen that two of your

co-defendants have had their standby counsel ask questions that were pre-prepared.

THE WITNESS: Right.

THE COURT: Do you intend to proceed in that manner

or --

THE WITNESS: No. With a narrative, Judge.

THE COURT: With a narrative. All right. You can go

ahead when you're ready.

THE WITNESS: Okay. So now it comes down to me. My job

is to convince Judge Cheesbro that this case should be

dismissed. This is a big burden, but I'll try to do my best. I

want to let -- I want to let the United States Attorney, Karl,

know that right now I want to stipulate to the fact that I have

a long, ongoing criminal history. If you'd like to skip the

litany of asking me about all my arrests, that will be fine

because I will stipulate that it's all true, and indeed, I've

been arrested seven times at the Pentagon alone. So if you want

to take that into consideration as a stipulation, I'm happy to agree to that.

I -- I -- I'm a father of eight children. So two of my

daughters are here with my wife today. Mary Evelyn is here and

Annie and my wife, Mary. Hi, Mary Evelyn. And I have six

daughters and two sons. I have two grandchildren who have both

been born just as recently as when Judge Baker was here. So

it's just been about 10 weeks, I guess, since the two new

grandchildren came into our lives.

Additionally, one of my jobs today, both to convince

Judge Cheesbro that we should have this case dismissed, is also

to not put anybody to sleep, and I'm going to do my best to do

that without boring anybody either, because a lot has been said,

and the judge has told us not to be redundant and repetitive

unnecessarily.

I was born on March 27th, 1956. My parents were Ann

O'Neill and Terrence O'Neill. My father died in 1960 in a

construction accident in Manhattan. He was only 28 years old,

leaving my mother a widow with two preschool-aged sons at the

age of 23. My mother, Ann O'Neill, died in 1998, so she's been

dead for 21 years.

My mother was a big influence on my religious faith, and

I'm going to establish my religious faith as being something

that's sincere. But I remember, as you folks remember who are

old enough, during the Vietnam War, when you would watch the

news at night on TV, there would be two sort of ticker tapes of

numbers going by, and the anchorperson would say, this number is

the number of people -- number of U. S. soldiers who died today

in the Vietnam War, and the second one was the running total of

the number of U. S. soldiers who had died during the course of

the war. So anybody -- so my mother, of course, you know, would

be watching the news with my brother and I sometimes, and she

would always say to us, "If this war is going on when you boys

get old enough to be drafted, I'm going to take you to Canada,"

because my mother had experienced death of her husband at the

age of 23, and she was worried that she would have to experience

the death of her two sons as well, because the war was going on.

It was proliferating.

Regarding my Catholic faith, having been born in The

Bronx, New York and growing up in New York City, I was a great

fan of the New York Yankees, so I used to go to Yankee Stadium a

lot for baseball games, but the most exciting thing I ever did

at Yankee Stadium happened in 1965 when I was nine years old.

They announced at my church, Saint Anastasia Church in

Douglaston, Queens, that they were going to have a raffle, and

the raffle was to win a ticket to go to Pope Paul, VI's, Mass at

Yankee Stadium. And when I heard about this raffle, I was

pretty excited to be able to go to a Mass at Yankee Stadium that

was going to be celebrated by the Pope.

So I went to the raffle, and I put my name in, and sure

enough, my name got drawn out, and I won a ticket to go to

Yankee Stadium by myself at the age of nine, to go to Pope Paul,

VI's Mass. And that certainly was a remarkable thing for me as

a young child to be able to go and have a Mass celebrated by the

Pope.

I also went to a Mass of Dom Helder Camara (ph) at Yankee

Stadium as well, Brazilian prophet. But, anyway, that sort of

was the beginning of my journey as a Catholic and my devotion to

the church.

I work now as a chaplain at Wake Med Hospital in

Raleigh, along with my wife. We visit the sick, and we bring

the Eucharist to the sick, and a lot has been said about the

Eucharist here. The Eucharist, of course, is Holy Communion,

which is a sacrament. It's all the same thing. So we bring the

Eucharist.

And Mark was testifying that during his time in the

jail, he never had a liturgy, an actual celebration of the Mass

and only -- I think you only got the sacrament four times, you

said, and it wasn't very common in the Glynn County Jail to be

able to receive the sacrament.

I would prefer, rather than to talk about the compelling

interests that the government has and that the defendants have,

I would prefer to say that we all have the same compelling

interest, that we're really here today because we share a

compelling interest in preserving life. Nobody wants war.

Nobody wants to see nuclear weapons used.

Judge Cheesbro said at the beginning of this hearing,

the beginning of the hearing on November 7th, that it's

indisputable that these weapons are horrific and dangerous.

It's not a matter of dispute. So I think the compelling

interest, ironically, is one that we share.

I wanted to sing the song "Why Can't We Be Friends" when

I first sat down, because I really, really want us to really

share a compelling interest in saving the world. As I look

around the room and I know the people here who have children.

Several of my friends in this room are grandparents. I and my

wife are now grandparents. Many of us in this room have

children. We're sharing our lives together as parents. We have

a compelling interest to save the world from destruction. We

have a compelling interest to fight global warming and to keep

the seas from rising and to keep the temperatures from rising

and to keep those nuclear weapons from being used and to abolish

them. So we do share a common and compelling interest. We want

peace in the world.

And while we might have some disagreement about the

tactics of that, I think that this is the thing that we share.

I'm guessing -- and it's just a guess, but I'm guessing

that even though most people in the courtroom today happen to be

Catholic, which would be unusual, that almost everybody in this

courtroom would probably profess some fidelity to Christianity,

to a belief in the Prince of Peace, to a belief that a better

world is possible, a belief in the power of prayer, a belief in

prophetic witness, a belief in sacramental witness, that we

would really share a lot more values than separate us, that

we're united in our beliefs about that.

In scripture Jesus talks about putting before us death

and life, that we should choose life. We call Jesus the

nonviolent Savior, the Prince of Peace. We celebrate that

fidelity to nonviolence to love.

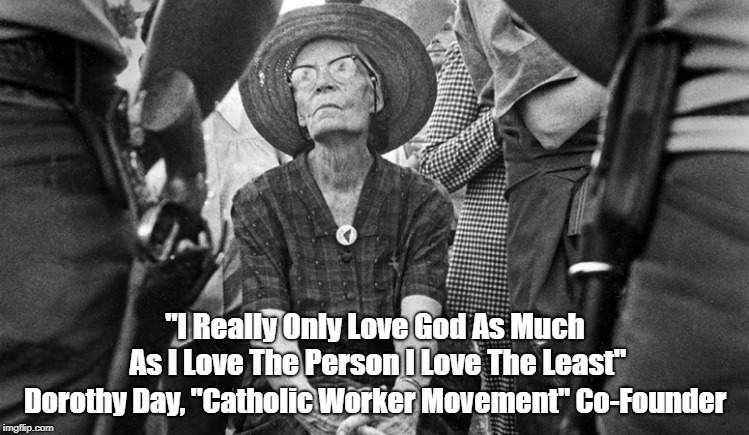

Martha testified at length about the inspiration of her

grandmother; and when I was young in 1978, I went to the

Catholic Worker, as Carmen referred to as the mother house in

New York City. I went to one of the Friday night round table

discussions, and that particular night there was a priest by the name of

Henri Nouwen, a beloved author, was speaking, and Dorothy

was quite elderly at that point. It was maybe a year

was quite elderly at that point. It was maybe a year

before she died or a year-and-a-half before she died. She

wasn't coming down to things quite as regularly, but this

particular night to hear Henri Nouwen, Dorothy came down to the

auditorium to hear Henri Nouwen speak. And I was in awe of

Dorothy and never had the guts to like walk up to her and

introduce myself or anything. It's not that I was shy, but I

was kind of shy about that.

But I was standing in the kitchen after Henri Nouwen's

talk, and I was getting myself a cup of tea, and I felt a tap on

my shoulder, and it was Dorothy Day tapping me on the shoulder,

Martha Hennessy's grandmother. And Dorothy Day said, "Hello, my

name is Dorothy." She shook my hand. She said, "Would you like

to join me for a cup of tea?" And invited me to her table to

share a cup of tea. That was a momentous moment in my Catholic

spiritual growth, that this servant of God, a woman who is

likely to become a saint, invited me to come down and have a cup

of tea with her.

I can't say that I recall much of the dialogue that we

shared, and I don't really think I said much, but she was asking

me a lot of questions about myself, and that was sort of Dorothy

Day's way. Another year later I was at Dorothy Day's wake and

funeral in New York City that was attended by Cesar Chavez and

Daniel Berrigan and Abbie Hoffman and a lot of interesting

people, I. F. Stone, and some of the people

in this courtroom, but it was also remarkable to be at that.

I think that we came to Kings Bay to express our

religious belief because it's a place where there's a secret

being kept. And we have to be able to expose the secret that

when the base commander was sitting in this seat on November

7th, he didn't want to name the sin. Maybe he didn't see it as

a sin. But the base commander mentioned the Trident II D5

missile. He did not refer to it as a nuclear weapon. He did

not refer to it as a first-strike weapon. In fact, he referred

to it as a second-strike weapon.

But the point is that we came to Kings Bay to recognize

the sin of Trident, specifically the sin of the D5 missile. It

is the most insidious, deadliest, horrific weapon ever built.

It has no right to exist. The Trident II D5 missile equals the

opposite of God. It is absolutely a sin. It needs to be

recognized as a sin, and that's why we're all here today,

because it is an abomination.

So the seven of us went to Kings Bay to say no to that

abomination, no to that sin. And, yes, we had to go there,

because that's the place where the sin is being committed.

Now, one of the things that has been very shocking to me

since we went to jail -- we went to Kings Bay, you know, on

Martin Luther King's anniversary of his death, 50 years, and by

the way, in my biographic, I'm a journalist. I've been working

as a journalist probably for about 35 years, and one of the --

I've done a lot of writing about religion, and I've had the good

fortune to interview Coretta Scott King; Martin Luther King,

III; Yolanda King -- the late Yolanda King, Martin Luther King's

daughter, has since died; Jesse Jackson three times; Shirley

Chisholm; Vincent Harding; some pretty -- and I'm not even

saying everybody. I've had the opportunity to speak to some of

the most profound and prophetic people; Nobel Prize winners,

several; Peace Prize winners, I've spoken to -- interviewed

several of them, and in my capacity as a journalist, I've been

able to learn a lot from a lot of people. That's the nice thing

about having

access to prophetic people as a journalist, you get

to ask them questions, and it's kind of an incredible thing and

a real honor.

So as a writer and a religion writer, I've been able to

sort of come into contact with these incredible witnesses to

God's truth and to be able to say, wow, this is pretty amazing

stuff that I'm being told here.

So then what happens is what I call -- and I think the

great Biblical example, the miracle that Jesus kind of does

several times, well, the several miracles, you know, feeding the

masses and large groups, but Jesus restores sight to the blind.

That's one of Jesus' major miracles. And we realize that the

miracle of restoring sight to the blind has a physical component

to it, the person can see again, but it also has a spiritual

component to it, because once we can see, then we have the

responsibility of sight. We can't say that we're blind to the

truth.

So I always see that healing of the sightless person as

also endowing the sightless person with truth, spiritual truth

that can no longer be denied. So for me, maybe that meeting of

Dorothy Day or going to Pope Paul, VI's Mass was sort of a

spiritual opportunity for me to see differently, to see with

clear eyes what was going on in the world.

When we came here, one of the things I realized -- and I

thought, well, I'm here with Dorothy Day's granddaughter; Father

Steve Kelly, one of the most prominent Jesuit priests in the

world. I'm here with Elizabeth McAlister, you know, a 20th

Century giant of the peace movement, the anti Vietnam War

movement; with my three other Catholic Worker friends, and I

thought to myself, you know, we're going to be big shots down

there in Georgia. You know, people are going to be, wow, we

want to hear what these people have to say. And I was humbled.

I was humbled. I never realized how inconsequential this act

is. Nobody cared. Nobody cared at all.

I sent three op eds to the Florida Times Union, and the

editor turned all three down. I sent an op ed -- and I'm an op

ed writer -- to the Atlanta Constitution. It was irrelevant.

It was turned down. I was really surprised of how

inconsequential it was that the seven of us came here and got

arrested at Kings Bay and nobody really cared about it.

But it got me to thinking, if in fact the seven of us

came here to expose this sin and nobody cared, well, what did

that say about the importance of us coming here? It made it

even more profoundly important that we come here, because --

now, maybe I'm being a bit judgmental to say nobody cared.

Maybe that's really too strong a language. Nobody realized what

we were talking about. It was like these seven people are

really odd balls. I mean, maybe they said we were fanatics or

zealots, but whatever it was, it just didn't conger up any fears

or worries. Nobody was worried.

So we had this visit from the Catholic priest who comes

to see us from Our Lady Star of the Sea at St. Marys, Georgia.

The priest comes to see us to bring us Holy Communion. The four

of us, Steve, Carmen, Mark and I sit down, and the priest does

the communion service. He gives us the Holy Eucharist, and then

he says to us, "I've really been caused some trouble by you guys

in my Catholicism because the people in the pews at my church,

they want to know how seven people can break into this base and

damage government property and claim to be doing it in the name

of Jesus and in the name of their Catholic faith, and I don't

know what to tell them."

Now, that was a profound moment for me, but the nice

thing was that this priest listened to us. So for 30 minutes he

just listened. The only time he had a disclaimer is when he

said, "I don't even believe in guns," he said. That's the only

time he spoke, but listened very carefully. And, fortunately,

we had Father Kelly with us, who is seminary educated; Mark,

seminary educated and were able to speak his language. But 30

minutes passed, and that priest completely understood us,

politically and theologically, and he wrote an email to that

effect afterwards.

But part that was -- I mean that flummoxed me was that

for four years this priest sat in his rectory overlooking the

harbor of St. Marys, seeing those Trident submarines float by,

and never once did he contemplate the fact that the entire

community of St. Marys, the lives, the livelihood of that

community is predicated on the end of the world, that these

weapons which represent without a doubt, weapons that can end

life as we know it on Planet Earth, were inconsequential, even

to the priest. He'd never thought about it.

So our Catholic faith compels us to come here to speak

about something so dangerous and so horrific, something that

represents such a threat to our families, to our children, to

our grandchildren, so we engage in something that's unorthodox,

for lack of a better word. You know, that's been brought out

through the U. S. Attorney's questions. You hammered on things;

you painted on things; you wrote on things; you broke in; you

cut locks. And, you know, I really want to argue that this was

theatrical in nature. What we did was theatrical, because in

order to get some attention to this issue, we had to do

something spectacular. So, indeed, this was a spectacular

thing. That's why we're all gathered in the courtroom talking

about it now, because we had to do something spectacular. If

we'd come to the base and just held up signs, this would not

happen. The Trident wouldn't be on trial. The D5 would not be

identified as the sin that nobody wants to talk about.

So because we were theatrical and because we did these

kind of wild things, for lack of a better word, we're having

this conversation, which I think, even though now this

conversation might be boring to some of the people in here, I

think there's going to come a time in all of our lives,

unfortunately, when we're going to look back on this

conversation and we're going to say it was a profound moment in

our lives when we talked about something really meaningful that

we preferred not to talk about. So, in essence, we have forced

a conversation to go to a place where people don't want it to

go.

One of the things that the Kings Bay Plowshares

represent, and it's part of our religious faith, is identifying

the sin, naming the sin and opposing the sin, dissenting to the

sin. So one of the things that's really a shame is that our

government right now is not interested in dissent. Dissent is

kind of a dirty word. We prefer that everybody marches in

lockstep in support of the Trident system, believing in the

government's take on it, that it's a second-strike deterrent

that keeps us all safe. We want -- that's what really the

government wishes everybody felt that way.

The government wishes that we weren't here saying that

we don't feel that way. So dissent is something that we

express, something that religious people express when it's this terrible sin.

So we know in the history of this country that some of

the worst evils in this country that have been changed; for

instance, slavery, segregation, women not having the right to

vote, child labor laws, all of these things I point out were

immoral, but maybe not felt that way at the time. They were

accepted at the time. But people of conscience dissented.

People of conscience did theatrical things. Like women chained

themselves to the Statue of Liberty. But in many cases people

died. People sat in at lunch counters; that was theatrical.

People did things for religious reasons to call attention to a

great evil. And ultimately those evils were changed.

Of course, it's our hope -- and, again, our shared

common vision, our shared compelling interest is to hope that we

can have a world without war and a world without nuclear

weapons. That's our prayer, and that's something we can all say we agree on.

Now, we've talked about the burden that this represents

to our faith, and I'll say, for my faith, obviously when I go to

work at the hospital, as far as I know, I'm the only employee

and probably the only chaplain wearing an ankle monitor in the

hospital. I am -- and when I go to the YMCA and I'm in the

locker room, it's quite obvious, and that is a way to sort of

call attention to this shamefulness that I'm under the -- I'm

under the government's watch, I'm on the government's watch list.

And certainly that's a burden. That's a burden to do that.

The time that we spend in jail is the time away from the

Eucharist, a time away from our religious practice. That's a

burden. But I sort of view a burden -- and I know I have to

speak about the burden that I'm experiencing myself, and I am

experiencing a burden myself because of the nature of this

prosecution, the likelihood that I'm going to be going to prison

and so on. But I also see the burden as our burden. It's a

universal burden and that one of our jobs here and one of our

burdens as people of faith is to be able to speak up in defense

of those who are burdened by the same things, but have no

access to speak about that burden.

So in a sense the burden of others is my burden. But

that's the nature of our religious faith, because we can't

separate our religious faith and our religious practice from our

lived lives. They're the same thing. They're not -- they're

not distinct. They're the same thing.

So our Catholic faith calls us to uphold the sanctity of

life. We are burdened because they are burdened. We take on

the burden of those who are powerless. And our Catholic faith

calls us to preserve life and to be stewards of God's creation.

I guess I'll close with a couple things about the

compelling interest again. As I said, it's our shared

compelling interest to prevent nuclear war; and really, even

with -- the government claims that their compelling interest is

to protect the base. But they're really saying that they're

protecting these weapons of mass destruction, because they

believe that somehow those weapons keep us safe. I mean, that's

the government line. The compelling interest is that these

weapons keep us safe. And we believe that the compelling

interest is the common good, which is endangered and jeopardized

by the weapons of mass destruction.

So I think sometimes when we look at the compelling

interest, we forget. For example, when Jesus cleansed the

temple of the money changers, He's not disputing that the

compelling interest of selling the animals to people who had to

participate in these ritual sacrifices was legitimate and

compelling, but He saw the excess of that and that His temple

had become a den of thieves, and then He overturned the tables

and threw out the money changers, because there was a

greater compelling interest.

A greater compelling interest is what we are aware of

here at the Trident base, and that's to save humanity from its

own hand, from destruction by its own hand.

So, in essence, I'd like to say that I see my job as

being an Evangelist. That's language that most Christians can

relate to. To be an Evangelist is very different than being a

fundamentalist, but an Evangelist is somebody who wants to

proclaim prophetically the Good News. So I call myself a

peace Evangelist, and part of the peace Evangelism that I'm

partaking of has led to my being here today.

Thank you, Judge.

THE COURT: Thank you, Mr. O'Neill. Questions?

Cross-examination from the government?

MS. SEMALES: Just briefly, Your Honor.

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MS. SEMALES:

Q. Hi, Mr. O'Neill. How are you?

A. Hi, Katelyn.

Q. You testified on direct that you'd stipulate to your

criminal history; is that correct?

A. Yes, ma'am.

Q. And you also testified that you had seven arrests at the

Pentagon?

A. Yes. I think I -- yeah, seven arrests at the Pentagon,

that's right.

Q. And one of those arrests was for depredation, throwing

blood; isn't that right?

A. Twice. Well, one was dismissed, but twice for blood, yes.

Q. And you were also arrested in Orlando in, I believe, 1992?

A. That was a Plowshare action.

Q. For conspiracy to commit damage and for committing damage

to Army property?

A. Almost the same charges as here, except for the

destruction charge I didn't have and the trespass charge.

Q. And you were convicted of those charges?

A. And I spent two years in federal prison.

Q. You're making my job easy, Mr. O'Neill. You had another

arrest in 1982; is that correct, at an Air Force base, for

trespass?

A. Right. I went to prison then, too. Well, no, the '82 one

was at Fort Bragg, and I went to prison for that one, too. That

was for impeding traffic.

Q. And you admit that when you went to the naval base to

Kings Bay in this incident, that you and your co-defendants,

you cut the gate; correct?

A. I cut the gate. Well, I cut the lock. I was very

surprised that you guys found it.

Q. And that you and your co-defendants threw blood?

A. We didn't all throw blood, but I did throw blood on the --

Q. But some of you --

A. -- insignia, that's right.

Q. And cut fences and brought tools onto the base, everything

that --

A. We didn't have to cut a fence, but -- because we went

through the gate.

Q. Concertina wire.

A. Oh, that was Carmen.

Q. Not you specifically.

A. The ones -- oh, those of us who went to the shrine didn't

have to cut a fence. So, yeah.

Q. And you never asked the naval base commander or anybody

at the naval base for permission to come onto the base --

A. Never asked permission, I didn't.

Q. -- did you? No further questions.

A. Thank you, Katelyn.

THE COURT: Any additional cross-examination from

co-defendants?

DEFENDANT KELLY: Just a couple.

(Nothing omitted)

PATRICK O'NEILL - CROSS-EXAMINATION BY DEFENDANT KELLY:

Q. It's hard to articulate -- thank you for your testimony.

It's hard to articulate. Have you observed the pattern in your

own life in dealing with the government authority, military

authority, and in the instance of not only this -- these

proceedings, do you see an attitude emerging or could you

typify the attitude of the government and this approach about

asking their permissions?

A. Well, I understand why -- why the U. S. Attorney is asking

that question, because you are making sure that we dotted

our Is and crossed our Ts --

THE COURT: Mr. O'Neill, I believe there may be a

receiver that got knocked off there.

THE WITNESS: Oh, it's on the floor.

THE COURT: Thank you.

BY FATHER KELLY:

Q. I can ask the question again or do you --

A. Yeah. Go ahead. Rephrase it, Steve. Yeah, thanks.

Q. In your own life and your interactions with either the

government or military authorities and your observation and

participation in these proceedings, what is emerging in terms

of the prospects of asking permissions?

A. Okay. When you have my reputation in North Carolina,

having been arrested at several military bases over a long

period of many years, let's just say that you get to be a known

entity. Okay.

So when I show up at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base or at

Fort Bragg in North Carolina, two places where I've been

arrested, I am noticed right away. And even when there's an

open house happening at a base -- now, both of those bases are closed.

But even when there's open houses at those bases, I am stopped

and not allowed to go in. Okay.

Now, I've been arrested twice for charges that I would

consider the charge of talking too much. I asked the police,

how come I'm not allowed to go in? This is a public activity

today. It's an air show or whatever is going on. How come I'm

not allowed to go in? And so I engage in a conversation, a

respectful conversation, and the way the conversation has

developed -- and this has happened three different times -- is

that I keep asking questions; the police and the military police

get tired of me asking my -- hearing my questions and don't want

to answer them and say, "If you ask another question, you're

going to jail," which I always do ask another question and then

I end up going to jail for talking too much.

None of those charges have ever stuck. I've never been

found guilty in any of those cases where I've talked too much,

but what that has succeeded of doing is depriving me of my

constitutional right to speak, to go onto the base, to be part

of a public witness, but I'm being discriminated against because

I'm seen as somebody who might do something, not because of

something -- I'm not being arrested for something I did. I'm

being arrested for something I might have done. So asking

permission has never worked for me, Steve.

Q. One further question. In your opinion -- and you've

participated in all of these -- can the government and perhaps

even the military, can they recognize -- and you've been

observing these proceedings -- can they recognize a religious

act?

A. Do they recognize it?

Q. Can? Are they able to?

A. Can the government do that?

Q. In your opinion.

A. Well, are we talking about the government as an entity or

are we talking about --

Q. How about the U. S. Attorneys?

A. How about Captain Carter, Sergeant Carter who approached us?

Q. I never get a word in edgewise.

A. Go ahead. Try and ask the question again.

Q. How about the U. S. Attorneys? Do you think they can

recognize a religious act?

A. Yeah, and I think they recognize it, and I think they like

me.

Q. And, just finally, you're basically you're very sincere

about your going onto the base to bring the Word there; is that right?

A. One of the most profound testimonies today was when Carmen

Trotta was questioned about going into a deadly force zone, and

he said, "That's amazing, isn't it?" Because he amazed himself.

I can't tell you how scary it is to slip through a gate at that

naval station and walk down a grass path not knowing what's

going to happen. It's one of the most frightening things that

anybody can imagine. And it's scary as could be, and it makes

you want to vomit. And we do it reluctantly. We do it because

we feel the Holy Spirit grabbing us by the scruff of the neck

and dragging us along, at least I did.

It's a horrible thing to have to do. It's a horrible

thing to have to face this kind of a situation, and I try my

best to make it as least adversarial as possible. I want to be

able to be friends with these four people and everybody else

in this courtroom for the rest of my life. I hope they write to me in prison.

DEFENDANT KELLY: I have nothing further. Thank you.

CROSS-EXAMINATION BY MR. CLARK:

Q. Earlier you described some of the actions taken at the

naval base as theatrical or spectacular. Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Would you also agree that many of the sacraments are

likewise spectacular?

A. Yeah, that's a good -- that's a good way to describe it.

You know, one of the questions that Karl asked way back

in the beginning was -- to the professor was the seven sacraments, and

the seven sacraments are spectacular. They are spectacular.

And when I bring the Eucharist to a sick person in the hospital,

I'm bringing the Body of Christ. So what Catholics believe is

that the Blessed Sacrament is Jesus Incarnate. Okay. We

believe that the words that Jesus spoke at the Last Supper, "do

this in memory of Me" means that the sacrament, the bread has

become the Body of Christ. So when you bring that to somebody,

and I tell the people -- because sometimes people feel, well,

I'm not worthy to receive the sacrament. Catholics have a

tremendous amount of guilt; I'm not worthy to receive the

sacrament. So I turn to that sick person in the bed, and I say,

"Jesus said, 'Only the sick need a physician.' I am the

physician." I turn to them and say, "Jane, you're in this

hospital bed sick, and I" -- and I take out the picks that has

the Blessed Sacrament in it, "and I have the physician right

here. You're worthy to receive it."

It is a spectacular moment, because the church teaches two

things. It's the Body of Christ, and it's a healing sacrament,

and if you receive this sacrament, you're going to experience

God's healing. That's a miracle.

Q. So it is fair, then, to characterize your actions on April

4th -- or April 5th, I know there's some debate about the time,

but April 4th, April 5th -- as being sacramental and based on

your deeply held religious beliefs?

A. Yeah, and I find it easier to say sacramental than it is

to say prophetic, because I don't want to refer to myself as a

prophet. I think that we can engage in prophetic acts, but I

humbly don't feel comfortable with that label. But to say

something is sacramental is saying that it's holy, that it's

sacred, and that I can certainly say.

Q. And Mr. Knoche had asked Ms. Hennessy earlier about if the base were to allow them -- or you guys time or access, say they let you, you know, on Saturday at 2 you're allowed to go to the missile shrine to engage in symbolic denuclearization or some designated time or area near the site of the nuclear weapons, would that enable you to fulfill your religious obligation, your belief that you need to perform this sacrament?

A. Well, I mean, we're not discussing at length what this

contract would look like, but it sounds -- it sounds

interesting. Sounds like something I certainly would want to

hear more about.

Q. And I guess maybe to make it a little more clear, there is

no requirement, at least to you or in your mind, that it be done without permission. If you were given permission to allow (sic) the site, you could achieve the same goal?

A. That's right. And one of the things that was testified to

when the U. S. Attorney asked several witnesses would a ban and bar letter have been acceptable, all I can say is on April 5th if somebody had handed me a ban and bar letter, I would have hit I-95 as quickly as possible heading home, and I wouldn't have come back.

Q. You've complied with every court order issued by the

Court, haven't you?

A. Yes.

MR. CLARK: Thank you.

CROSS-EXAMINATION BY MS. McDONALD:

Q. Mr. O'Neill, I just want to clarify a couple of the

concepts that have been testified to. Number one, this use of

the word theatrical, would you agree with me that a lot of

Catholic rituals or sacramental acts can be characterized as

theatrical, such as burning incense, wearing of the long robes,

burning candles, things of that nature?

A. I wouldn't want to confuse ritual with theatrical. I

think the reason that this action was theatrical is because we

tried to look for some tremendous way to express our feelings.

Right? And we had to be creative. I guess maybe creative is

the better word for it. So if you want to say that there's a

creative component to religious ritual and a creative component

to what we've done, I can go with that. But theatrical really is something

that's more -- I guess I'm more referring to the word drama here.

Q. Okay.

A. We had to be dramatic because that's the only way that we

got the attention of the government. We came there and said,

look what you're doing here, and we did it dramatically, and we did it in a way that demanded that they pay attention to us, which wouldn't have happened if like Karl asked, if we held signs outside the gates, you know, well, I'm arguing, of course, that what we did was even inconsequential on this level, but certainly if we'd held signs, it would have been inconsequential completely.

Q. Okay. So some of the acts that were taken that led to

this criminal prosecution you're saying were creative and some were sacramental? Is that fair?

A. They were all sacramental.

Q. Okay.

A. No, there's no doubt that this was -- you know, and I want

to be -- I didn't say this to you, Judge, because I said it to

Judge Baker, but I want to say it to you. I'm not the kind of

person who gets up into this seat and says, I'm right, what I

did was right, God's on my side, no question about it. I don't

feel that way at all.

I come into this seat to testify as a humble person, just

like everybody else, searching for God's truth. I recognize the

fact that the distinction between pride and prophetic witness is as thin as a hair. If we've done anything as a matter of pride, it's a fraud. But if we have done it because of our fidelity to God, even if it isn't necessarily what God wanted us to do, but we did it because we believed it was God's will, then it's something divine. But I realize how close those two things are, and I'm very careful not to declare myself as knowing for sure that I've done God's will. I'm not sure.

Q. Was that your attempt?

A. It absolutely was my attempt.

Q. And then you were asked some questions about some of your prior arrests

and prosecutions. In any of those did the government ever offer

other alternatives as opposed to criminal prosecution?

A. There have been some times when I wasn't arrested and I

was given a ban and bar letter, which is similar to what the

base commander testified to. And I did not violate those ban

and bar letters.

Q. Were you given any other alternatives in this particular

case by the government, other than criminal prosecution?

A. No.

MS. McDONALD: Thank you.

THE WITNESS: This is your last chance to cross-examine,

anybody.

THE COURT: Any further cross-examination?

All right. Mr. O'Neill, as I've done with the other pro

se defendants, you would ordinarily have an opportunity for

redirect here, if you were represented, and because you've

testified by narrative, I'll give you an opportunity to offer

anything to the Court that you think needs to be considered

at this time based on the cross-examination that's been

performed.

THE WITNESS: I think for the sake of everybody's mental

health, I'll just get off the stand, Judge.

THE COURT: Thank you, Mr. O'Neill.

No comments:

Post a Comment