Much of America as we know it evolved in the 19th century, as we'll explore in a series of three conversations this week with writers who seek out new ways to understand old events.

There's no shortage of intrepid tales about the advent of the American rail system: Starting in the 1860s, rail companies built one track after another, across mountains and deserts, from the Midwest to California. Brilliant engineering combined with the muscle of immigrant labor unified America — or so the story goes.

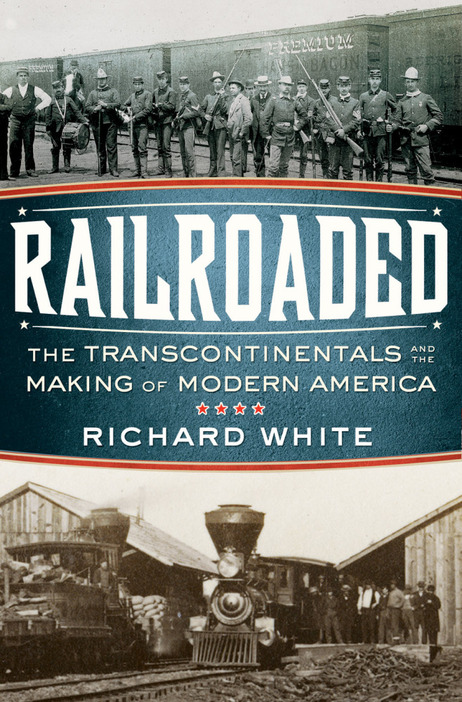

But that's not the story Richard White tells in his new book Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. White describes how the rail corporations shaped the U.S. economy as we know it today — and not entirely for the better.

Hear Other Stories In This Series

"They bring about a great deal of political controversy and corruption," White tells NPR's Steve Inskeep. "They yield environmental damage, they are conceptually grand, and in practice, they really amount to being disasters in many respects."

Interview Highlights

On the railroad's legacy of corruption

"It establishes a kind of networking between politics and business that persists to this day. Essentially for me, corruption is quite simple: It's the trading of public favors for private goods, and that's what happens repeatedly with the railroads and the federal government."

On the transcontinental railroads being on a whole new scale

"This is the invention of the modern corporation. This is why railroads are so feared: It's the first time that Americans come face to face with a new way of organizing the economy on a scale that they had never seen before. The result of this is not just going to be political corruption but, they think, an intervention into the economic lives of ordinary Americans that frightens them."

On the Western railroads, which, more than the Eastern railroads, relied almost entirely on government funding

"Western railroads, particularly the transcontinental railroads, would not have been built without public subsidies, without the granting of land and, more important than that, loans from the federal government ... because there is no business [in the West at that time,] there is absolutely no reason to build [railroads] except for political reasons and the hope that business will come.

"What we're talking about is 1,500 or more miles between the Missouri River and California, in which there are virtually no Anglo-Americans. Most railroad men look at this, including [railroad magnate Cornelius] Vanderbilt, and they want nothing to do with it."

On why the story of Grenville Dodge — the Civil War veteran and engineer who is said to have discovered the Union Pacific's key pass through the mountains — is presented somewhat less heroically in Railroaded

"He's an impressive guy and certainly he tells wonderful stories — including the story of finding that pass. I'm not the first one to point out that that pass shows up nowhere in his contemporary accounts. It's not in his diaries, it's not in his letters — it's a story that he makes up later. And that's what Grenville Dodge is very good at: making up wonderful stories about Grenville Dodge, which is not to say he's not a competent engineer.

"The problem with Grenville Dodge is that he is surprisingly competent at times, and at times he represents the worst of the gilded age. He is corrupt, he's a politician, he will go out and become a lobbyist for the Union Pacific and for the Texas Pacific. What he is is very adroit at finding ways in which he can get public favors for private railroads."

On Grenville Dodge inventing some corporate lobbying techniques — manufacturing "grass roots" support that is actually "AstroTurf"

"What he realizes is that lobbyists themselves have limited ability to gain what they want if they operate only in Washington, D.C. They have to appear to be channeling real public desire for whatever it is they're advocating. So what Dodge does is go back out and organize publicity campaigns, so he makes it appear that what Union Pacific wants and the Texas Pacific wants is what local people want. But all of this uproar of popular opinion has really been organized by Grenville Dodge. ... This is AstroTurf."

On both despising and admiring historical figures like Dodge

"It's easy when you're writing about these people to despise them, but it's also tempting to admire them. They are inventing, in many ways, our modern world. This is the first time that they're seeing many of these things — and they see them fresher than we do. ... They're making it up as they go along, and I learned an awful lot from watching them do it."

Excerpt: 'Railroaded'

Chapter 1: Genesis

It is easier, more delightful, and more profitable to build with other peoples'money than our own.

—Newton Booth

In 1860, the year he won the Republican nomination for the presidency, Abraham Lincoln traveled from his home in Springfield, Illinois, to New York, a journey of about 825 miles as the crow flies, to give his famous Cooper Union speech. Lincoln, however, traveled considerably farther than the crow. Departing on Wednesday, February 22, it took Lincoln six hours to go by rail from Springfield to State Line, on the Indiana border, where he arrived at 4:30 p.m. and transferred to the Toledo, Wabash, and Western. The second leg of his trip took him from State Line to Fort Wayne, Indiana, where he arrived just in time to board another train, the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne, and Chicago. It was now 1:12 a.m. on Thursday, February 23. The third leg, from Fort Wayne to Pittsburgh, took a little over twenty-four hours. He arrived in Pittsburgh at 2:20 a.m. on Friday, February 24. The fourth leg of the trip advanced him from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia and through yet another day. That train, fourteen hours late, reached Philadelphia early on Saturday morning, February 25. The final leg of his trip carried him from Philadelphia to New York. He waited several hours for the Pennsylvania Railroad train to New York, about as long as that train took to go between Philadelphia and Jersey City, from which he had to take the Paulus Street Ferry for New York. Reduced to numbers, the trip of twelve hundred miles involved five trains, two ferries, four days, and three nights. The numbers do not capture the discomfort imposed by schedules that shuttled passengers between trains in the middle of the night. They do not record the adrenaline rushes involved in making some transfers and the drowsy tedium of waiting to make others. This was train travel before the Civil War: at once technologically impressive and nearly incoherent. It was exhausting, aggravating, uncomfortable, yet, withal, far better than any existing alternative. Americans were prepared to love trains, hate trains, and be unable to live without them.

Like the Union itself, American railroads did not quite cohere. The railroads had grown as fast, and were as disarticulated, as the nation that contained them. The 31,286 miles of tracks united the country only on a map. Impressive in the aggregate, these lines could hardly be thought of as a system or even a collection of systems. A major reason was that there was no single standard gauge for tracks. It was as if hobbyists were trying to connect Lionel with HO tracks. They would not fit together.

The standard gauge in North America today is 4 feet 8 1/2 inches. It is an utterly arbitrary number that spread because the builders of a small English coal road had early success in building larger roads in England by using that gauge and because others conformed to it. By 1860 it was the dominant gauge in much of the eastern United States. It accounted for roughly one-half the total mileage, but it was only one of the more than twenty gauges in use. Five feet was the standard gauge in the South, and 5 feet 6 inches became the standard gauge in Canada.

An individual railroad stopped where its track stopped, but, as long as the gauges were the same, a railroad's rolling stock could happily roll on along some other railroad's track, even if few roads at the time allowed such a thing. Different gauges were akin to dams in the thin streams of iron flowing through the continent. When gauges changed, traffic stopped. Passengers had to walk to a new train; freight had to be off-loaded at considerable expense or cars had to be jacked up and their wheels adjusted before the train could continue its transit. The lines that flowed so cleanly on a map ruptured in reality because of a small difference in space between the rails. Sometimes the different lines coming into a city never actually met. Freight coming into Philadelphia had to be off-loaded and carted across the city to get out of Philadelphia. In Ohio the usual mishmash of gauges and opposition to bridging the Ohio River forced the ferrying of cars. Railroads often did not share terminals, and tracks did not connect their different terminals. A railroad system was "articulated,"the way the bones of a skeleton might connect, but the muscles and tendons were wagons, ferries, and human bodies. Take them away, and the railroad skeleton fell into unconnected pieces.

The Civil War probably destroyed more railroads than it built, but it contributed a great deal to the organization of railroads and even more to the creation of financial and governmental institutions that would in the years following the war breed railroads like rabbits. The war gave free rein to men willing to take command, to imagine great things, to innovate, to experiment, and to lose all hold on reality. The abilities to organize, imagine, squander, and wreck unfortunately did not come in separate containers. They were part of a single package that when opened in the 1860s would create the first transcontinental railroads.

Excerpted from Railroaded by Richard White. Copyright 2011 by Richard White. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Co.

No comments:

Post a Comment